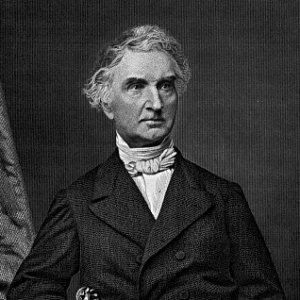

Justus von Liebig

BiographyLiebig was born in Darmstadt into a middle class family. From childhood he was fascinated by chemistry. He was apprenticed to the apothecary Gottfried Pirsch (1792-1870) in Heppenheim.Liebig attended the University of Bonn, studying under Karl Wilhelm Gottlob Kastner, a business associate of his father. When Kastner moved to the University of Erlangen, Liebig followed him and later took his doctorate from Erlangen. Liebig did not receive the doctorate until well after he had left Erlangen, and the circumstances are clouded by a possible scandal. Also at Erlangen, Liebig fell in love with the poet August von Platen-Hallermünde (1796-1835) who wrote several sonnets dedicated to Liebig. He left Erlangen in March 1822, in part because of his involvement with the radical Korps Rhenania (a nationalist student organization) but also because of his hopes for more advanced chemical studies. In autumn 1822 Liebig went to study in Paris on a grant obtained for him by Kastner from the Hessian government. He worked in the private laboratory of Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, and was also befriended by Alexander von Humboldt and Georges Cuvier (1769-1832). After leaving Paris, Liebig returned to Darmstadt and married Henriette Moldenhauer, the daughter of a state official. This ended Liebig's relationship with Platen. In 1824 at the age of 21 and with Humboldt's recommendation, Liebig became a professor at the University of Giessen. He established the world's first major school of chemistry there. He received an appointment from the King of Bavaria to the University of Munich in 1852, where he remained until his death in 1873 in Munich. He became Freiherr (baron) in 1845. He founded and edited from 1832 the journal Annalen der Chemie, which became the leading German-language journal of Chemistry. The volumes from his lifetime are often referenced just as Liebigs Annalen; and following his death the title was officially changed to Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. Research and developmentLiebig improved organic analysis with the Kaliapparat -- a five-bulb device that used a potassium hydroxide solution to remove the organic combustion product carbon dioxide. He downplayed the role of humus in plant nutrition and discovered that plants feed on nitrogen compounds and carbon dioxide derived from the air, as well as on minerals in the soil. One of his most recognized and far-reaching accomplishments was the invention of nitrogen-based fertilizer. Liebig believed that nitrogen must be supplied to plant roots in the form of ammonia. Though a practical and commercial failure, his invention of fertilizer recognized the possibility of substituting chemical fertilizers for natural (animal dung, etc.) ones. He also formulated the Law of the Minimum, stating that a plant's development is limited by the one essential mineral that is in the relatively shortest supply, visualized as "Liebig's barrel". This concept is a qualitative version of the principles used to determine the application of fertilizer in modern agriculture.He was also one of the first chemists to organize a laboratory as we know it today. His novel method of organic analysis made it possible for him to direct the analytical work of many graduate students. The vapor condensation device he popularized for his research is still known as a Liebig condenser, although it was in common use long before Liebig's research began. Liebig's students were from many of the German states as well as Britain and the United States, and they helped create an international reputation for their Doktorvater. In 1835 he invented a process for silvering that greatly improved the utility of mirrors. Liebig's work on applying chemistry to plant and animal physiology was especially influential. At a time when many chemists such as Jöns Jakob Berzelius insisted on a hard and fast separation between the organic and inorganic, Liebig argued that "...the production of all organic substances no longer belongs just to the organism. It must be viewed as not only probable but as certain that we shall produce them in our laboratories. Sugar, salicin [aspirin], and morphine will be artificially produced." Liebig's arguments against any chemical distinction between living (physiological) and dead chemical processes proved a great inspiration to several of his students and others who were interested in materialism. Though Liebig distanced himself from the direct political implications of materialism, he tacitly supported the work of Karl Vogt (1817-1895), Jacob Moleschott (1822-1893), and Ludwig Buechner (1824-1899).

Liebig played a more direct role in reforming politics in the German states through his promotion of science-based agriculture and the publication of John Stuart Mill's Logic. Through Liebig's close friendship with the Vieweg family publishing house, he arranged for his former student Jacob Schiel (1813-1889) to translate Mill's important work for German publication. Liebig liked Mill's Logic in part because it promoted science as a means to social and political progress, but also because Mill featured several examples of Liebig's research as an ideal for the scientific method. Liebig is also credited with the notion that "searing meat seals in the juices." This idea, still widely believed, is not true. Working with Belgian engineer George Giebert, Liebig devised an efficient method of producing beef extract from carcasses. In 1865, they founded the Liebig Extract of Meat Company, marketing the extract as a cheap, nutritious alternative to real meat. Some years after Liebig's death, in 1899, the product was trademarked "Oxo". After World War II, the University of Giessen was officially renamed after him, "Justus-Liebig-Universit⇒t Giessen". In 1953 the West German post office issued a stamp in his honor. ReferencesGlas, E (1976), "The Liebig-Mulder controversy. On the methodology of physiological chemistry.", Janus; revue internationale de l'histoire des sciences, de la médecine, de la pharmacie, et de la technique 63 (1-2-3): 27–46.Sonntag, O (1974), "Liebig on Francis Bacon and the utility of science.", Annals of science 31 (5): 373–86, 1974 Sep. Kempler, K (1973), "[Justus Liebig]", Orvosi hetilap 114 (22): 1312–7, 1973 Jun 3. Halmai, J (1963), "Justus Liebig", Orvosi hetilap 104: 1523–4, 1963 Aug 11. Berghoff, E (1954), "Justus von Liebig, founder of physiological chemistry.", Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 66 (23): 401–2, 1954 Jun 11. Schmidt, F (1953), "To Justus von Liebig on his 150th birthday, 12 May 1953", Pharmazie 8 (5): 445–6, 1953 May. Schneider, W (1953), "Justus von Liebig and the Archiv der Pharmazie; in memory of Liebig's birthday, 12 May 1803", Archiv der Pharmazie und Berichte der Deutschen Pharmazeutischen Gesellschaft 286 (4): 165–72. G. F. Knapp (1903). "Zur Hundertsten Wiederkehr: Justus von Liebig nach dem Leben gezeichnet". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 36 (2): 1315 – 1330. Georg Freiherr von Liebig (1890). "Nekrolog: Justus von Liebig. Eigenh⇒ndige biographische Aufzeichnungen". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 23 (3): 817 – 828. "Zur Erinnerung an Justus von Liebig". Journal für Praktische Chemie 8 (1): 428 – 458. 1873. |