Phylogeny and Adaptive Radiation

Phylogeny and

Adaptive Radiation

Phylogeny

Shared derived characters between annelids and arthropods gave strong support to the hypothesis that both phyla originated from a line of coelomate segmented protostomes, which in time diverged to form a protoannelid line with laterally located parapodia and one or more protoarthropod lines with more ventrally located appendages. The molecular evidence supporting alignment of annelids and arthropods with separate superphyla is at dramatic variance with our long-held belief that the two phyla are closely related. Separation into separate superphyla implies that metamerism in the two groups arose independently and is a convergent character. We must observe, however, that the analyses supporting an Ecdysozoa- Lophotrochozoa hypothesis suffer an important defect: failure to support monophyly of Annelida and Mollusca.

Whether phylum Arthropoda itself is monophyletic has also been controversial. Some scientists have contended that Arthropoda is polyphyletic and that some or all the present subphyla are derived from different annelid-like ancestors that underwent “arthropodization.” The crucial development is the hardening of the cuticle to form an arthropod exoskeleton, and most of the features that distinguish arthropods from annelids result from the stiffened exoskeleton (see Prologue for this section). For example, once the vital role of the coelomic compartments as a hydrostatic skeleton was gone, intersegmental septa were unnecessary, as was a closed circulatory system. Jointed appendages, of course, are necessary if the external surface is hard, and bodywall muscles of annelids could be converted and inserted on the considerable inner surfaces of the cuticle for efficient movement of body parts. Compared with annelids, there was a great restriction in permeable surfaces for respiration and excretion. Thus arthropods could have evolved more than once. However, other zoologists argue strongly that the derived similarities of the arthropod subphyla strongly support monophyly of the phylum. The phylum Tardigrada may be the sister taxon to arthropods, with phylum Onychophora being the sister taxon to the combined Arthropoda and Tardigrada (Lesser Protostomes ). A cladogram depicting possible relationships is presented in Lesser Protostomes .

Some evidence based on ribosomal RNA sequences supports monophyly of Arthropoda and the inclusion of Onychophora in the phylum.* These data also suggest that myriapods (millipedes and centipedes) are a sister group to all other arthropods and that crustaceans and insects form a monophyletic group! If these conclusions are supported by further investigations, our concepts of arthropod phylogeny and classification are subject to major revision.

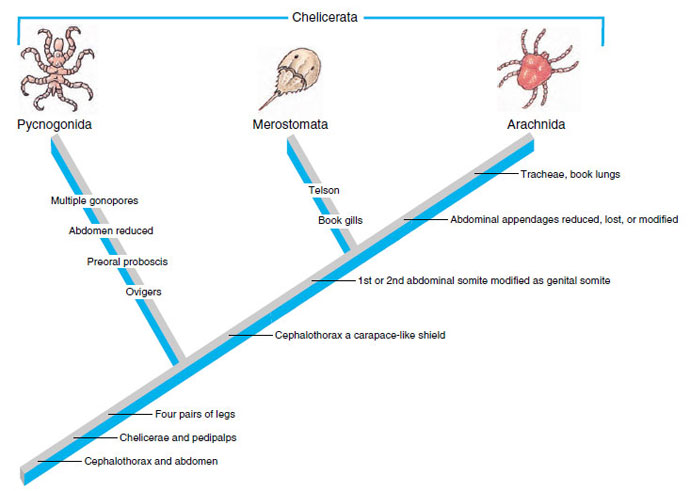

Controversy on phylogeny within Chelicerata also exists, especially on the position of Pycnogonida (Figure 18-18). Some workers place pycnogonids as the sister group to chelicerates in a larger grouping called Cheliceriformes.

Adaptive Radiation

Annelids show limited tagmatization and little differentiation of appendages. However, in arthropods an adaptive trend has been toward pronounced tagmatization by differentiation or fusion of somites, giving rise in more derived groups to such tagmata as head and trunk; head, thorax, and abdomen; or cephalothorax (fused head and thorax) and abdomen. The primitive arthropod condition is to have similar appendages on each somite, and each somite bears a pair of appendages. More derived forms have appendages specialized for specific functions, or some somites lack appendages entirely.

Much of the amazing diversity in arthropods seems to have developed because of modification and specialization of their cuticular exoskeleton and their jointed appendages, resulting in a wide variety of locomotor and feeding adaptations.

Classification of Phylum Arthropoda

Subphylum Trilobita (tri´lo-bi´ta) (Gr. tri, three, + lobos, lobe): trilobites. All extinct forms; Cambrian to Carboniferous; body divided by two longitudinal furrows into three lobes; distinct head, thorax, and abdomen, biramous (twobranched) appendages.

Subphylum Chelicerata (ke-lis´e-ra´ta) (Gr. chele, claw, + keras, horn, + ata, group suffix): eurypterids, horseshoe crabs, spiders, ticks. First pair of appendages modified to form chelicerae; pair of pedipalps and four pairs of legs; no antennae, no mandibles; cephalothorax and abdomen usually unsegmented.

Subphylum Uniramia (yu-ni-ra´me-a) (L. unus, one, + ramus, a branch): insects and myriapods. All appendages uniramous; head appendages consisting of one pair of antennae, one pair of mandibles, and one or two pairs of maxillae.

Phylogeny

Shared derived characters between annelids and arthropods gave strong support to the hypothesis that both phyla originated from a line of coelomate segmented protostomes, which in time diverged to form a protoannelid line with laterally located parapodia and one or more protoarthropod lines with more ventrally located appendages. The molecular evidence supporting alignment of annelids and arthropods with separate superphyla is at dramatic variance with our long-held belief that the two phyla are closely related. Separation into separate superphyla implies that metamerism in the two groups arose independently and is a convergent character. We must observe, however, that the analyses supporting an Ecdysozoa- Lophotrochozoa hypothesis suffer an important defect: failure to support monophyly of Annelida and Mollusca.

Whether phylum Arthropoda itself is monophyletic has also been controversial. Some scientists have contended that Arthropoda is polyphyletic and that some or all the present subphyla are derived from different annelid-like ancestors that underwent “arthropodization.” The crucial development is the hardening of the cuticle to form an arthropod exoskeleton, and most of the features that distinguish arthropods from annelids result from the stiffened exoskeleton (see Prologue for this section). For example, once the vital role of the coelomic compartments as a hydrostatic skeleton was gone, intersegmental septa were unnecessary, as was a closed circulatory system. Jointed appendages, of course, are necessary if the external surface is hard, and bodywall muscles of annelids could be converted and inserted on the considerable inner surfaces of the cuticle for efficient movement of body parts. Compared with annelids, there was a great restriction in permeable surfaces for respiration and excretion. Thus arthropods could have evolved more than once. However, other zoologists argue strongly that the derived similarities of the arthropod subphyla strongly support monophyly of the phylum. The phylum Tardigrada may be the sister taxon to arthropods, with phylum Onychophora being the sister taxon to the combined Arthropoda and Tardigrada (Lesser Protostomes ). A cladogram depicting possible relationships is presented in Lesser Protostomes .

Some evidence based on ribosomal RNA sequences supports monophyly of Arthropoda and the inclusion of Onychophora in the phylum.* These data also suggest that myriapods (millipedes and centipedes) are a sister group to all other arthropods and that crustaceans and insects form a monophyletic group! If these conclusions are supported by further investigations, our concepts of arthropod phylogeny and classification are subject to major revision.

Controversy on phylogeny within Chelicerata also exists, especially on the position of Pycnogonida (Figure 18-18). Some workers place pycnogonids as the sister group to chelicerates in a larger grouping called Cheliceriformes.

|

| Figure 18-18 Cladogram of the chelicerates, showing one proposed ancestor-descendant relationship within the chelicerate clade. Shared derived characters used to construct the cladogram are shown adjacent to the branch lines (based on Brusca and Brusca, 1990). Some workers separate the Pycnogonida from the Chelicerata, placing it as the sister group to chelicerates in a larger Cheliceriformes grouping. |

Adaptive Radiation

Annelids show limited tagmatization and little differentiation of appendages. However, in arthropods an adaptive trend has been toward pronounced tagmatization by differentiation or fusion of somites, giving rise in more derived groups to such tagmata as head and trunk; head, thorax, and abdomen; or cephalothorax (fused head and thorax) and abdomen. The primitive arthropod condition is to have similar appendages on each somite, and each somite bears a pair of appendages. More derived forms have appendages specialized for specific functions, or some somites lack appendages entirely.

Much of the amazing diversity in arthropods seems to have developed because of modification and specialization of their cuticular exoskeleton and their jointed appendages, resulting in a wide variety of locomotor and feeding adaptations.

Classification of Phylum Arthropoda

Subphylum Trilobita (tri´lo-bi´ta) (Gr. tri, three, + lobos, lobe): trilobites. All extinct forms; Cambrian to Carboniferous; body divided by two longitudinal furrows into three lobes; distinct head, thorax, and abdomen, biramous (twobranched) appendages.

Subphylum Chelicerata (ke-lis´e-ra´ta) (Gr. chele, claw, + keras, horn, + ata, group suffix): eurypterids, horseshoe crabs, spiders, ticks. First pair of appendages modified to form chelicerae; pair of pedipalps and four pairs of legs; no antennae, no mandibles; cephalothorax and abdomen usually unsegmented.

-

Class Merostomata (mer´o-sto´mata)

(Gr. meros, thigh, + stoma,

mouth, + ata, group suffix): aquatic

chelicerates. Cephalothorax and

abdomen; compound lateral eyes;

appendages with gills; sharp telson;

subclasses Eurypterida (all extinct)

and Xiphosurida, horseshoe crabs.

Example: Limulus.

Class Pycnogonida (pik´no-gon´ida)

(Gr. pyknos, compact, + gony,

knee, angle): sea spiders. Small (3 to

4 mm), but some reach 500 mm;

body chiefly cephalothorax; tiny

abdomen; usually four pairs of long

walking legs (some with five or six

pairs); mouth on long proboscis; four

simple eyes; no respiratory or excretory

system. Example: Pycnogonum.

Class Arachnida (ar-ack´ni-da) (Gr. arachne, spider): scorpions, spiders, mites, ticks, harvestmen. Four pairs of legs; segmented or unsegmented abdomen with or without appendages and generally distinct from cephalothorax; respiration by gills, tracheae, or book lungs; excretion by malpighian tubules or coxal glands; dorsal bilobed brain connected to ventral ganglionic mass with nerves, simple eyes; chiefly oviparous; no true metamorphosis. Examples: Argiope, Centruroides.

Subphylum Uniramia (yu-ni-ra´me-a) (L. unus, one, + ramus, a branch): insects and myriapods. All appendages uniramous; head appendages consisting of one pair of antennae, one pair of mandibles, and one or two pairs of maxillae.

-

Class Diplopoda (di-plop´o-da) (Gr. diploos, double, + pous, podos, foot): millipedes. Body almost cylindrical;

head with short antennae and simple

eyes; body with variable number of

somites; short legs, usually two pairs

of legs to a somite; oviparous. Examples: Julus, Spirobolus.

Class Chilopoda (ki-lop´o-da) (Gr. cheilos, lip, + pous, podos, foot): centipedes. Dorsoventrally flattened body; variable number of somites, each with one pair of legs; one pair of long antennae; oviparous. Examples: Cermatia, Lithobius, Geophilus.

Class Pauropoda (pau-ro´po-da) (Gr. pauros, small, + pous, podos, foot) pauropods. Minute (1 to 1.5 mm); cylindrical body consisting of double segments and bearing 9 or 10 pairs of legs; no eyes. Example: Pauropus.

Class Symphyla (sym´fy-la) (Gr. syn, together, + phyle, tribe): garden centipedes. Slender (1 to 8 mm) with long, filiform antennae; body consisting of 15 to 22 segments with 10 to 12 pairs of legs; no eyes. Example: Scutigerella.

Class Insecta (in-sek´ta) (L. , cut into): insects. Body with distinct head, thorax, and abdomen; pair of antennae; mouthparts modified for different food habits; head of six fused somites; thorax of three somites; abdomen with variable number, usually 11 somites; thorax with two pairs of wings (sometimes one pair or none) and three pairs of jointed legs; usually oviparous; gradual or abrupt metamorphosis.