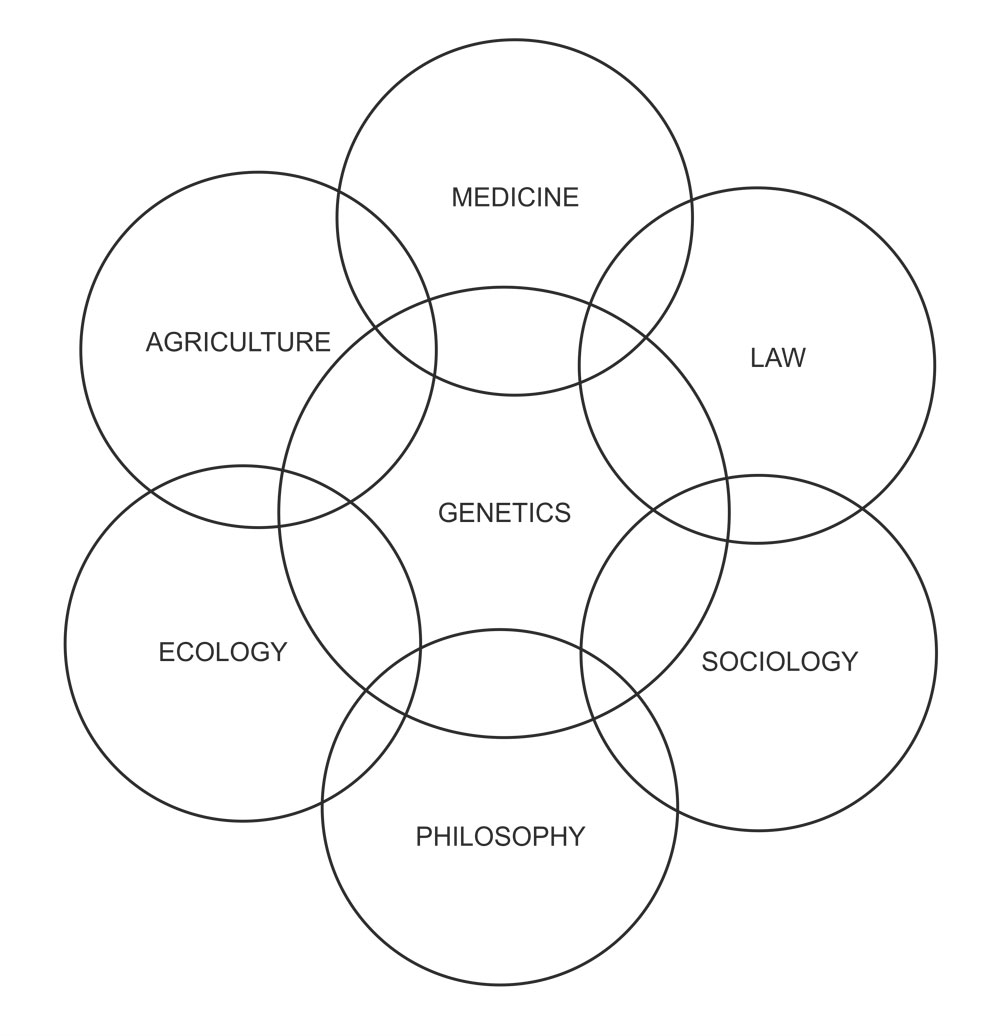

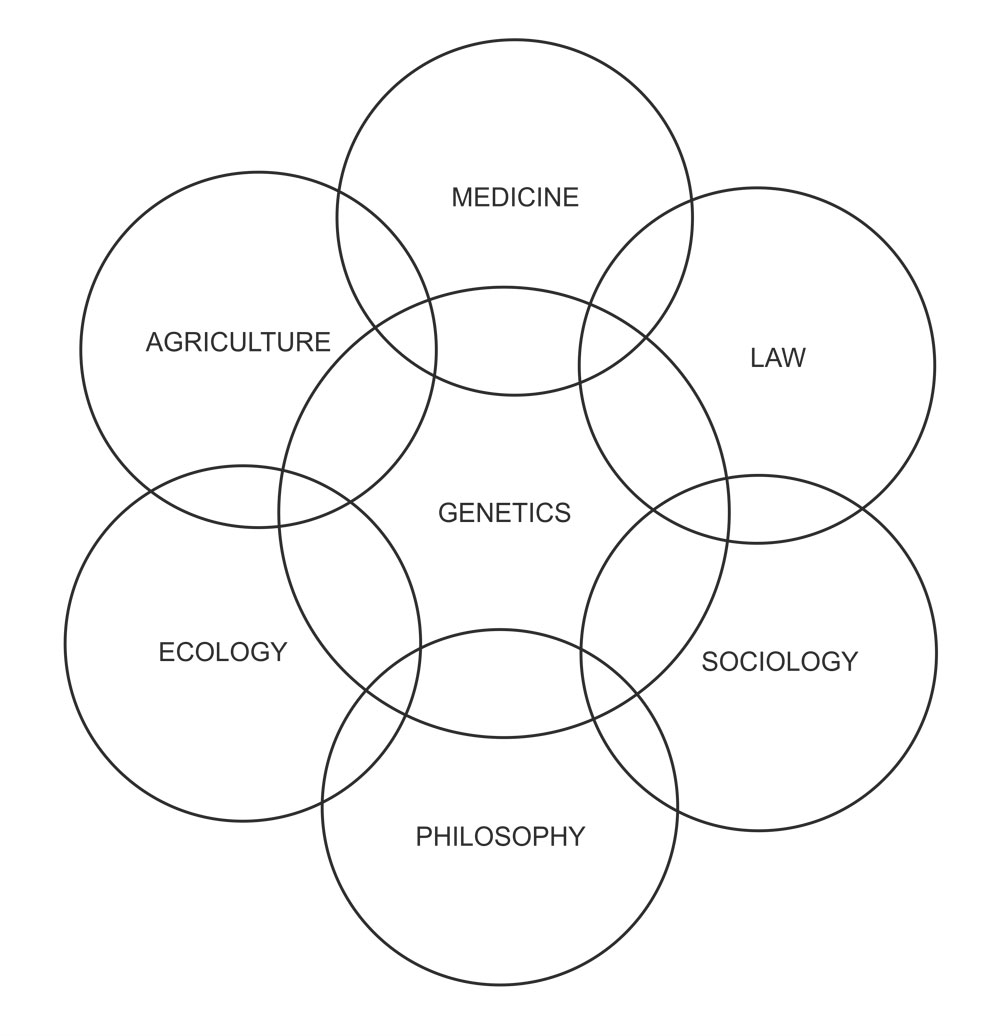

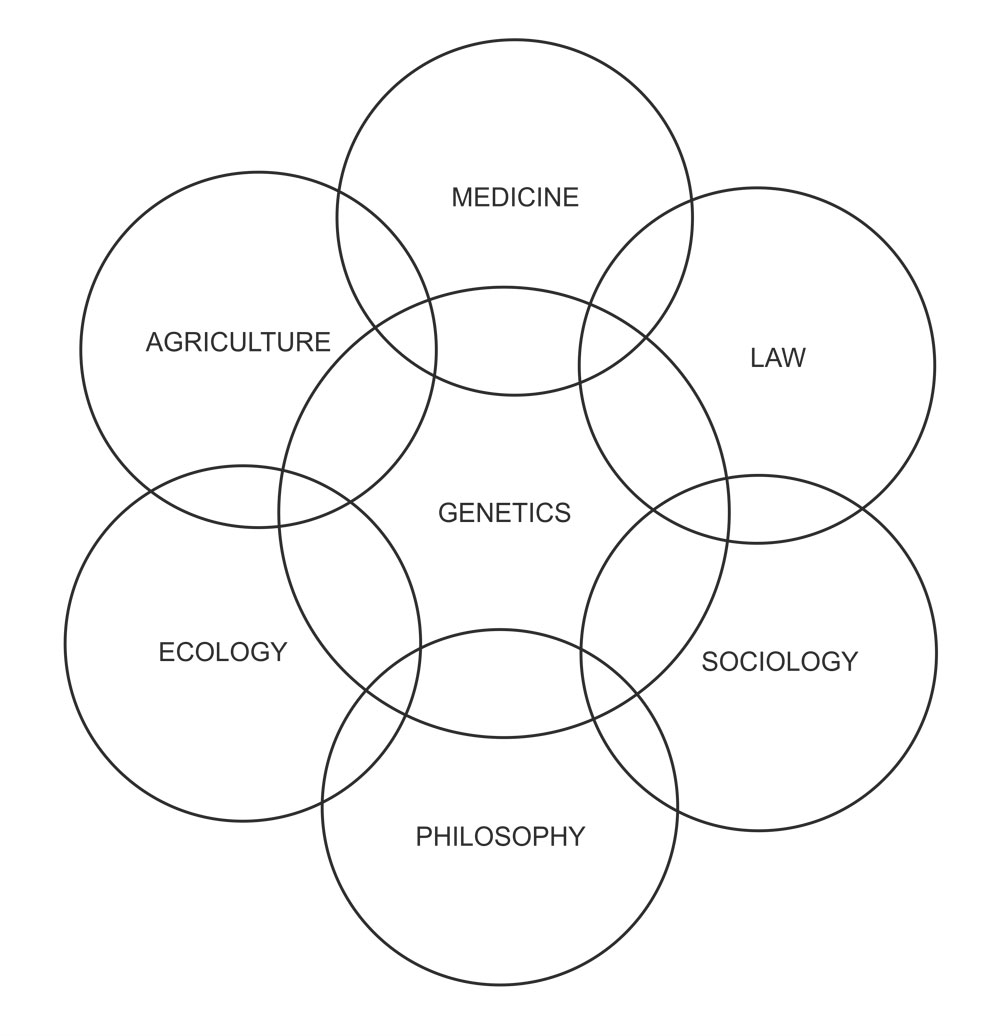

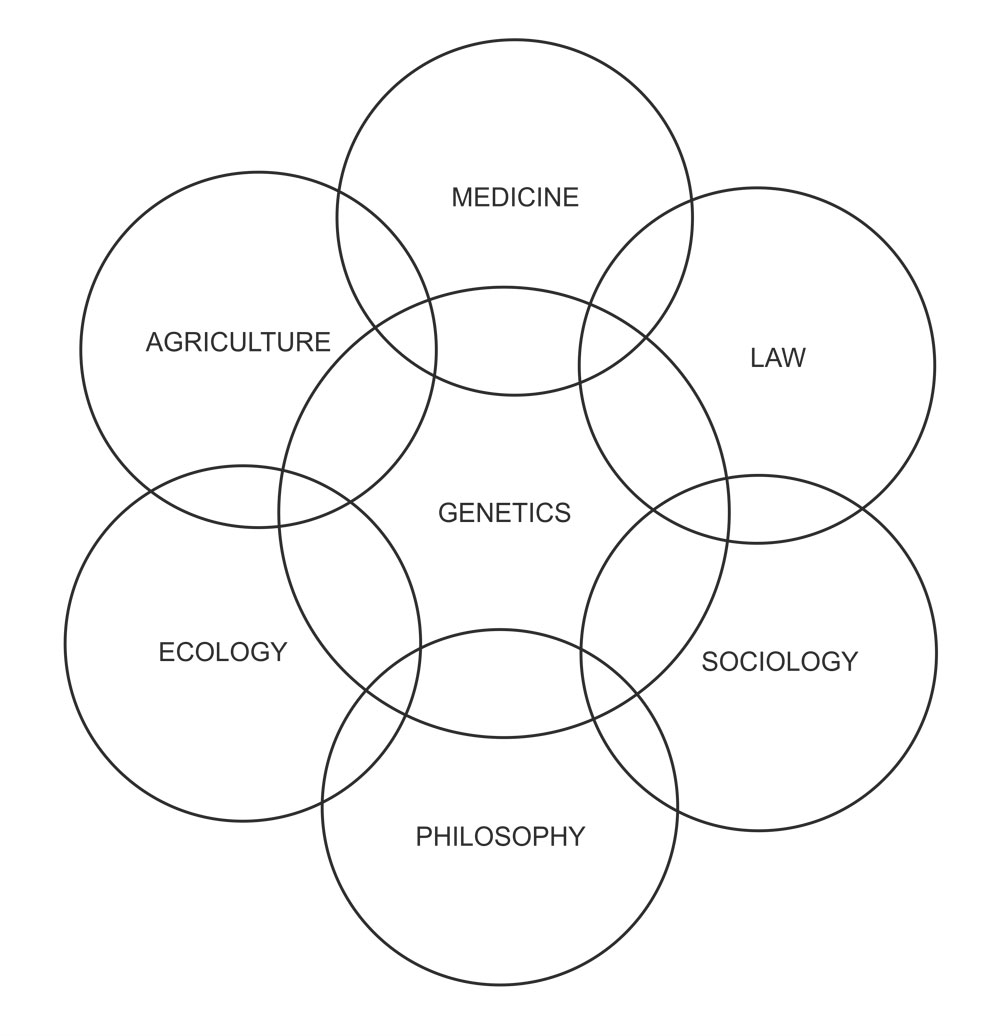

Fig. 1.4. Impact of genetics on different areas of human endeavour (redrawn from Suzuki et at., 1986).

During the last decade, the term reverse genetics has been frequently used for physical mapping and isolation of genes whose protein products are unknown. This has been suggested in contrast to forward genetics, where genes are mapped on the basis of phenotype, using the techniques of classical genetics. Recently (in 1991) the meaning of the term

reverse genetics has been redefined. It has been argued that in forward genetics, we start the study on the basis of phenotype, leading ultimately to the study of DNA sequences comprising the gene for this phenotype.

Therefore, even though the mapping and isolation of a gene for any trait (including those for human diseases) with unknown gene product is a spectacular achievement, but the approach cannot be termed reverse genetics for the simple reason that in this case also, we start the genetic study on the basis of phenotype and finally isolate the gene, albeit using sophisticated techniques of recombinant DNA. Therefore,

Paul Berg (Nobel Laureate) in a recent report (1991) suggested that the usage of the term reverse genetics be restricted to those studies, where we start the study with a DNA segment with unknown phenotypic effect, introduce this DNA (without any alteration or after modification) into a plant or an animal and then study its phenotypic effect. Production of transgenic plants and animals followed by a study of their phenotype or identification of regulatory DNA sequences using transgenic plants or animals or targeted alterations in genes at the molecular level are some examples of reverse genetics. These techniques of reverse genetics will be increasingly used in future leading to significant advances in our knowledge of genetics.

Fig. 1.4. Impact of genetics on different areas of human endeavour (redrawn from Suzuki et at., 1986).