Commercial Horticulture

Next time you eat a french fry, think about where the potato came from. Most of us are completely dependent on commercial horticulture to supply us with seeds, plants, produce, flowers, herbs, and all the products that are derived from them. We expect high-quality products at an affordable price. So what do you think are the biggest challenges to commercial horticulture and what can be done about them? Two of the greatest concerns are the access to good quality natural resources: water and soil. Other problems are the potential for catastrophic crop loss due to disease or bioterrorism, and international competition that drives down prices and makes it increasingly difficult for commercial farms to make a profit.Well water is preferred for irrigation because it is usually of a higher quality than surface water from ponds, lakes, or rivers, which can contain pathogens. Excessive use of groundwater through heavy irrigation causes geologic problems, such as those seen in California, Texas, Arizona, and some of the states surrounding the Gulf of Mexico. One of the best examples is seen in the experience of Mexico City. The water is withdrawn by wells from aquifers at a rate that is faster than the recharge of the aquifers by precipitation and percolation; if the soil pores that were once filled with water collapse, the aquifer cannot be recharged, the wells run dry, and the land sinks.

The rate of water withdrawal from the Colorado River and the current drought, combined with population growth in the sunny, warm regions of the Southwest, further endangers freshwater supplies and wreaks havoc on the environment. Commercial horticulture tends to follow the sun because warmer climates mean longer growing seasons, but there simply is not enough water to go around and the poor Colorado River is drained dry before it ever reaches the ocean. Additionally, heavy irrigation of soil in semiarid and arid regions creates problems with salination and poor soil fertility similar to those that caused the downfall of ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman agricultural productivity.

|

| Figure 6.1 Technicians inspect Russet potatoes, the potato of choicefor french fry processors. |

As urban sprawl encroaches on agricultural land, there are conflicts. The well-drained loamy soils that are perfect for growing crops are also ideal for building houses, and it is very tempting for a farmer who is barely getting by to sell the land to the highest bidder. When residential neighborhoods come into contact with farmland, there are concerns with dangers associated with pesticide drift and drinking water contamination. Across the United States, prime farmland is being turned into housing developments. Increased pressure for biofuels (such as ethanol, which is made from corn) may translate into even more land taken away from food production, with a corresponding increase in the amount of chemical fertilizers and herbicides applied.

The frozen-food industry often contracts with farmers to grow specific cultivars because the plants yield fruits or vegetables of a consistent size and quality that can be readily processed by their manufacturing equipment. One example is the Russet potato, the cultivar bred by Luther Burbank, which is the perfect size and has the best consistency for making french fries (Figure 6.1). The problem is that this potato cultivar is also prone to disease. Heavy applications of pesticides are required to produce a crop acceptable to factory owners. This is not in the best interests of the farmer, because land abused with heavy applications of chemical fertilizers and pesticides becomes less fertile over time and can endanger the health of the farmer. Other types of potatoes are disease resistant and do not require the pesticide use, but the factory wants the Russets so the farmer either produces them or loses the contract. Factory farms are one reason that farmers practice monocropping.

A problem with monocropping is the reduction in the genetic diversity of our food crops. High diversity means that a crop has many different varieties. Some of these may have traits for resistance to a particular disease. The lower the diversity of our food crops, the more susceptible they are to outbreaks of natural diseases or bioterrorism. Low crop diversity has led to catastrophic failure as a result of disease, because all the plants are susceptible to the same pathogens. The corn blight of 1970 wiped out most of the nation’s corn crop because growers all planted the same variety, which could not resist this microbial infection. Seed gene banks store genetic diversity for breeding new hybrids of important food crops, but unless diverse crops are planted in the field, a single disease can wipe out entire harvests.

|

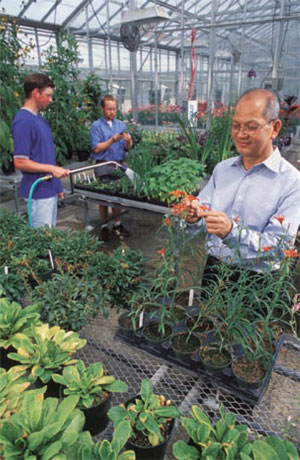

| Figure 6.2 Traditional greenhouse production of plants involves overhead irrigation as opposed to the method described in the text for hydroponics. Greenhouses allow for a controlled environment unsusceptible to harsh weather conditions, but plants are still prone to insect infestations and microbial diseases and must be carefully monitored. |

All of this sounds quite dreadful, but many commercial growers are implementing sustainable methods to overcome these problems and legislatures across the country are taking steps to conserve farmland and good freshwater. There is a long way to go. Consumer demand for organically grown produce helps to put pressure on the food processing industry, which in turn may help farmers who want to plant more diverse crops and reduce pesticide use.