Teeth and Skull

The shape and size of the skull and teeth determine the nature of the prey that can be manipulated and swallowed (Rieppel 1979). Like snakes, monitor lizards can swallow large prey items whole and they have similar adaptations as those of their limbless counterparts such as flexible joints between skull bones and an epiglottis that permits breathing even when the mouth is stuffed with food. Teeth are replaced at regular intervals throughout life (Edmund 1960, 1969), but in captivity regeneration slows down and sometimes stops in very old specimens (Bellairs & Miles 1960). The shape and relative size of monitor lizard skulls varies greatly, as does the shape, size and number of teeth. The most comprehensive study of monitor lizards' skulls is by Mertens (1942b). In the absence of first hand knowledge about a lizard's diet in the wild, a study of the dentition and skull can provide general clues about what its preferred prey might be.Species which feed on hard-shelled prey that require crushing before being swallowed tend to have thickened bones in the skull to which more massive jaw muscles can be attached . Lonnberg (1903) compared the skulls of Nile and water monitors of similar sizes and noted that the skull of the former weighed about three times more than that of the latter. The Nile monitor, the white-throated monitor and Gray's monitor all have large blunt teeth at the back of the jaws that, combined with the large jaw muscles, are capable of exerting enormous pressure on shelled animals. In Bose's monitor the rear teeth appear to have the same function, but the front teeth are sharper, longer and more curved. Durneril's monitor, which may feed largely on crabs, has very different teeth which are few in number but very sharp and strong and are used to puncture the shells of their prey rather than crushing them. In most species the primary purpose of the teeth is to hold prey that are able to move quickly and are very anxious to escape. ln sectivorous species such as the rough-necked monitor have much more delicate jawbones equipped with large numbers of small, sharp teeth. The yellow monitor, which often feeds on frogs, has similar numbers of teeth which are larger and straighter whilst the enigmatic Salvadori's monitor has very long conical-shaped teeth with which it is believed to capture birds and other fast moving vertebrates. But by far the most fearsome teeth in the family belong to the Komodo dragon . Said by tooth specialists to be more reminiscent of those of a shark or a Jurassic crocodile than any living lizard, the Komodo dragons' teeth bear hundreds of tiny serrations that enable the lizards to saw swallowable chunks from the carcasses of large animals by grasping the meat and rocking backwards and forwards. These teeth also allow them to disable enormous prey animals with a single bite by severing tendons in the leg (Auffenberg 1981). Some other species, such as the lace goanna (Greer 1989), also have serrated edges on their teeth, but no other monitor lizard appears to have teeth as well suited to slashing through flesh as those of the formidable dragon.

|

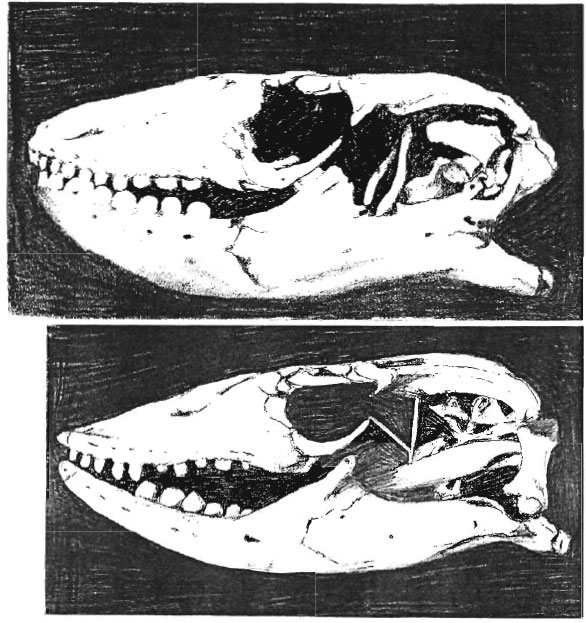

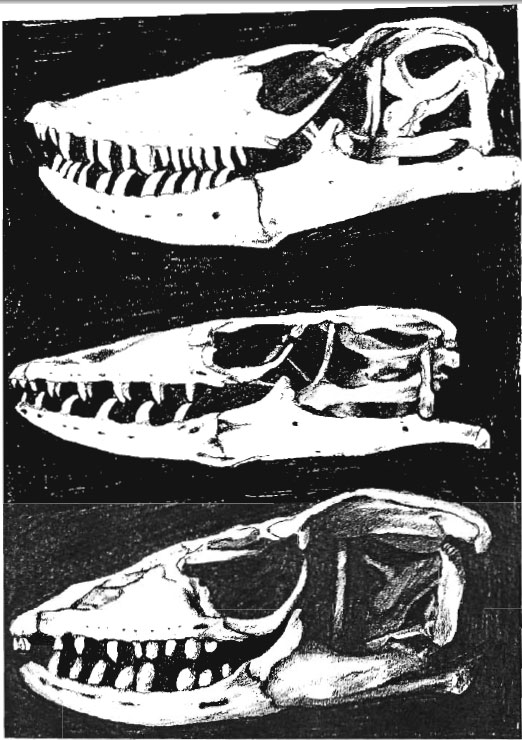

| Above: Skulls of white-throated monitor (top) and Nile monitor Below: Komodo dragon (top), water monitor, Gray's monitor (Tim Garner) |

|

The very earliest members of the family appear to have had grooved teeth capable of transmitting venom. No living monitor lizards have a poisonous bite but many species which regularly feed on carrion are hosts to particularly nasty bacteria in their mouths. Swabs taken from the mouths of wild Komodo dragons contain four types of wound-infecting bacteria, including "superbacteria" of the genus Proleus (Auffenberg 1981 ).

Superbacteria are very resistant to natural defence mechanisms and reproduce at phenomenal rates, soon wrning even a minor wound into a huge, festering sore. Thus even animals that initially escape from the dutches of a dragon may shonly afterwards find themselves disabled by a virulent infection that smells so strongly that all the monitor lizards in the vicinity are atuacted to it. Thankfully the animals loose these bacteria in captivity, and so it is presumed that they find their way into the lizards' mouths during meals of rotting flesh.

Attribution / Courtesy: Daniel Bennett. 1995. A Little Book of Monitor Lizards. Viper Press U.K.