Conservation

Content

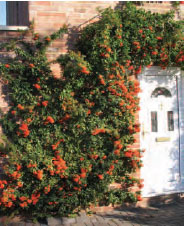

From the content of preceding paragraphs it can be seen that the provision of as extensive a system of varied habitats, each with its complex foodweb, in as many locations as possible, is increasingly being considered desirable in a nation’s environment provision. In this way, a wide variety of species numbers (biodiversity) is maintained, habitats are more attractive and species of potential use to mankind are preserved. In addition, a society that bequeaths its natural habitats and ecosystems to future generations in an acceptably varied, useful and pleasant condition is contributing to the sustainable development of that nation. The ecological aspects of natural habitats and horticulture have been highlighted in recent years by the conservation movement. One aim is to promote the growing of crops and maintain wildlifeareas in such a way that the natural diversity of wild species of both plants and animals is maintained alongside crop production, with a minimum input of fertilizers and pesticides. Major public concern has focused on the effects of intensive production (monoculture) and the indiscriminate use by horticulturists and farmers of pesticides and quick-release fertilizers. An example of wildlifeconservation is the conversion of an area of regularly mown and 'weedkilled' grass into a wild flower meadow, providing an attractive display during several months of the year. The conversion of productive land into a wild flower meadow requires lowered soil fertility (in order to favour wild species establishment and competition), a choice of grass seed species with low opportunistic properties and a mixture of selected wild flower seed. The maintenance of the wild flower meadow may involve harvesting the area in July, having allowed time for natural flower seed dispersal. After a few years, butterflies and other insects become established as part of the wild flower habitat. The horticulturist has three notable aspects of conservation to consider. Firstly, there must be no willful abuse of the environment in horticultural practice. Nitrogen fertilizer used to excess has been shown, especially in porous soil areas, to be washed into streams, since the soil has little ability to hold on to this nutrient. The presence of nitrogen in watercourses encourages abnormal multiplication of micro-organisms (mainly algae). On decaying these remove oxygen sources needed by other stream life, particularly fish (a process called eutrophication). Secondly, another aspect of good practice increasingly expected of horticulturists is the intelligent use of pesticides. This involves a selection of those materials least toxic to man and beneficial to animals, and particularly excludes those materials that increase in concentration along a food chain. Lessons are still being learned from the widespread use of DDT in the 1950s. Three of DDT’s properties should be noted. Firstly, it is long-lived (residual) in the soil. Secondly, it is absorbed in the bodies of most organisms with which it comes into contact, being retained in the fatty storage tissues. Thirdly, it increases in concentration approximately ten times as it passes to the next member of the food chain. As a consequence of its chemical properties, DDT was seen to achieve high concentrations in the bodies of secondary (and tertiary) consumers such as hawks, influencing the reproductive rate and hence causing a rapid decline in their numbers in the 1960s. This experience rang alarm bells for society in general, and DDT was eventually banned in most of Europe. The irresponsible action of allowing pesticide spray to drift onto adjacent crops, woodland or rivers has decreased considerably in recent years. This has in part been due to the Food and Environment Protection Act (FEPA) 1985, which has helped raise the horticulturist’s awareness of conservation. A third aspect of conservation to consider is the deliberate selection of trees, features and areas which promote a wider range of appropriate species in a controlled manner. A golf course manager may set aside special areas with wild flowers adjacent to the fairway, preserve wet areas and plant native trees. Planting bush species such as hawthorn, field maple and spindle together in a hedgerow provides variety and supports a mixed population of insects for cultural control of pests. Tit and bat boxes in private gardens, an increasingly common sight, provide attractive homes for species that help in pest control. Continuous hedgerows will provide safepassage for mammals. Strips of grassland maintained around the edges of fields form a habitat for small mammal species as food for predatory birds such as owls. Gardeners can select plants for the deliberate encouragement of desirable species (nettles and Buddleia for butterflies; Rugosa roses and Cotoneaster for winter feeding of seed-eating birds; poached-egg plants for hoverflies). It is emphasized that the development and maintenance of conservation areas requires continuous management and consistent effort to maintain the desired balance of species and required appearance of the area. As with gardens and orchards, any lapse in attention will result in invasion by unwanted weeds and trees. In a wider sense, the conservation movement is addressing itself to the loss of certain habitats and the consequent disappearance of endangered species such as orchids from their native areas. Horticulturists are involved indirectly because some of the peat used in growing media is taken from lowland bogs much valued for their rich variety of vegetation. Considerable efforts have been made to find alternatives to peat in horticulture and protect the wetland habits of the British Isles.

Large national collections include the National Fruit Collection at Brogdale, Kent (administered by Wye College) and the Horticultural Research International at Wellesbourne, Birmingham, holds vegetables. The Henry Doubleday Heritage Seed Scheme conserves old varieties of vegetables which were once commercially available but which have been dropped from the National List (and so become illegal to sell). They encourage the exchange of seed. The National Council for the Conservation of Plants and Gardens (NCCPG) was set up by the Royal Horticultural Society at Wisley in 1978 and is an excellent example of professionals and amateurs working together to conserve stocks of extinction threatened garden plants, to ensure the availability of a wider range of plants and to stimulate scientific, taxonomic, horticultural, historical and artistic studies of garden plants. There are over 600 collections of ornamental plants encompassing 400 genera and some 5000 plants. A third of these are maintained in private gardens, but many are held in publicly funded institutions such as colleges, e.g. Sarcococca at Capel Manor College in North London, Escallonia at the Duchy College in Cornwall, Penstemon and Philadelphus at Pershore College and Papaver orientale at the Scottish Agricultural College, Auchincruive. Rare plants are identified and classified as 'pink sheet' plants. Organic growing The organic movement broadly believes that crops and ornamental plants should be produced with as little disturbance as possible to the balance of microscopic and larger organisms present in the soil and also in the above-soil zone. This stance can be seen as closely allied to the conservation position, but with the difference that the emphasis here is on the balance of micro-organisms. Organic growers maintain soil fertility by the incorporation of animal manures, or green manure crops such as grass–clover leys. The claim is made that crops receive a steady, balanced release of nutrients through their roots in a soil where earthworm activity recycles organic matter deep down; the resulting deep root penetration allows an effective uptake of water and nutrient reserves. The use of most pesticides and quick-release fertilizers is said to be the main cause of species imbalance, and formal approval for licensed organic production may require soil to have been free from these two groups of chemicals for at least two years. Control of pests and diseases is achieved by a combination of resistant cultivars and 'safe’ pesticides derived from plant extracts, by careful rotation of plant species, and by the use of naturally occurring predators and parasites. Weeds are controlled by mechanical and heat-producing weed controlling equipment, and by the use of mulches. The balanced nutrition of the crop is said to induce greater resistance to pests and diseases, and the taste of organically grown food is claimed to be superior to that of conventionally grown produce. The organic production of food and non-edible crops at present represents about 5 per cent of the European market. The European Community Regulations (1991) on the 'organic production of agricultural products' specify the substances that may be used as 'plantprotection products, detergents, fertilizers, or soil conditioners'. Conventional horticulture is, thus, still by far the major method of production and this is reflected in this book. However, it should be realized that much of the subsistence cropping and animal production in the Third World could be considered 'organic’. |

|||||||||||||||||