The Elasmobranchii

This order contains the Sharks, the Rays, and the Chimoera.The integument may be naked, and it never possesses scales like those of ordinary fishes; but, very commonly, it is developed into papillae, which become calcified, and give rise to toothlike structures: these, when they are very small and close-set, constitute what is called shagreen. When larger and more scattered, they form dermal plates or tubercles; and when, as in many cases, they take the form of spines, these are called dermal defences, and, in a fossil state, ichthyodorulites. All these constitute what has been called a "placoid exoskeleton;" and, in minute structure, they precisely resemble teeth, as has been already explained. The protruded surfaces of the dermal defences are frequently ornamented with an elegant sculpturing, which ceases upon that part of the defence which is imbedded in the skin. The dermal defences are usually implanted in front of the dorsal fins, but may be attached to the tail, or, in rare cases, lie in front of the paired fins. The spinal column exhibits a great diversity of structure: from a persistent notochord exhibiting little advance upon that of the Marsipobranchii, or having mere osseous rings developed in its walls, to complete vertebrae, with deep conical anterior and posterior concavities in their centra, and having the primitive cartilage more or less completely replaced by concentric, or radiating, lamallae of bone. In the Rays, indeed, the ossification goes so far as to convert the anterior part of the vertebral column into one continuous bony mass.

The terminal part of the notochord is never enclosed within a continuous bony sheath, or urostyle. The extremity of the vertebral column is generally bent up, and the median finrays which lie below it are, usually, much longer than those which lie above it, causing the lower lobe of the tail to be much larger than the upper. Elasmobranclis with tails of this conformation are truly heterocercal, while those in which the fin-rays of the tail are equally divided by the spinal column, or nearly so, are diphycercal. The Monkfish (Squatina) and many other Elasmobranchii are more diphycercal than heterocercal.

The ribs are always small, and may be quite rudimentary.

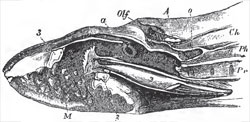

The skull is composed of cartilage, in which superficial pavement-like deposits of osseous tissue may take place, but it is always devoid of membrane bone. When movable upon the spinal column, it articulates therewith by two condyles.

In its general form and structure, the cartilaginous skull of an Elasmobranch corresponds with the skull of the vertebrate foetus in its cartilaginous state, and there are usually more or less extensive membranous fontanelles in its upper walls. The ethmoidal region sends horizontal plates over the nasal sacs, the apertures of which retain their embryonic situation upon the under-surface of the skull.

Neither premaxillae nor maxillae are present, the "jaws" of an Elasmobranch consisting, exclusively, of cartilaginous representatives of the primary palato-quadrate arch and of Meckel's cartilage.

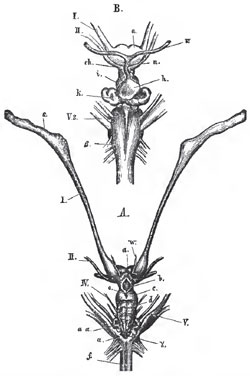

The former of these, the so-called upper jaw, may either be represented, as in the Chimaera (Fig. 33), by the anterior portion (B, D) of a triangular cartilaginous lamella, which stretches out from the sides of the base of the skull, and is continuous with the representative of the hyomandibular suspensoriura; or there may be, on each side, a cartilaginous bar movably articulated in front with the fore-part of the skull; and, posteriorly, furnishing a condyle, with which the ramus of the lower jaw, representing Meckel's cartilage, articulates.

In the latter case, which is that met with in the Sharks and Rays (Figs. 34 and 35), a single cartilaginous rod (g) is movably articulated with the skull, in the region of the periotic capsule, upon each side; and, by its opposite extremity, is connected by ligamentous fibres both with the palatoquadrate (h) and with the mandibular or Meckelian cartilage (Mn). This cartilaginous suspensorium represents the hyomandibular and the symplectic bones of the Teleostei, and gives attachment to the hyoidean apparatus (Hy). The latter consists of a lateral arch upon each side, united with its fellow, and with the branchial arches, by the intermediation of medial basal elements below; and it is succeeded by a variable number of similar arches, which support the branchial apparatus.

From the hyoidean and from the branchial arches cartilaginous filaments pass directly outward, and support the walls of the branchial sacs. Superficial cartilages, which lie parallel with the branchial arches, are sometimes superimposed upon these. There are no opercular bones, though cartilaginous filaments which take their place (Fig. 34, Op) may be connected with the hyomandibular cartilage; and, in the great majority of the Elasmobranchii, the apertures of the gill-sacs are completely exposed. But in one group, the Chimaera, a great fold of membrane extends back from the suspensorial apparatus, and hides the external gill-apertures.

Large accessory cartilages, called labial, are developed at the sides of the gape in many Elasmobranchii. (Figs. 34 and 35, i, k, l.)

The pectoral arch consists of a single cartilage on each side. The two become closely united together in the ventral median line, and are not directly connected with the skull. The pelvis is also represented by a pair of cartilages, which may coalesce, and are invariably abdominal in position.

There are always two pairs of lateral fins corresponding with the anterior and posterior limbs of the higher Vertebrata. The pectoral fins, the structure of which has already been described, are always the larger, and sometimes attain an enormous size relatively to the body.

In these fishes, teeth are developed only upon the mucous membrane which covers the palato-quadrate cartilage and the mandible. They are never implanted in sockets, and they vary greatly in form and in number.

In the Sharks they are always numerous, and their crowns are usually triangular and sharp, with or without serrations and lateral cusps. As a rule, the anterior teeth on each side have more acute, the posterior more obtuse crowns. In the Port Jackson shark (Cestracion), however, the anterior teeth are not more acute than the most obtuse teeth of the others, while the middle teeth acquire broad, nearly flat, ridged crowns, and the hindermost teeth are similar but smaller. The Rays usually have somewhat obtusely-pointed teeth, but in Myliobates, the middle teeth have transversely-elongated, and the lateral ones hexagonal, flat crowns, and the various teeth are fitted closely by their edges into a pavement. In Aetobatis only the middle transversely elongated teeth remain. In the Sharks and Rays the teeth are developed from papillae, or ridges, situated at the bottom of a deep fold within the mucous membrane of the jaw. The teeth come to the edge of the jaw, and, as they are torn away or worn down by use, they are replaced by others, developed, in successive rows, from the bottom of the groove. No such successive development takes place in the Chimaera.

As in other fishes, there are no salivary glands. The wide oesophagus leads into a stomach which is usually spacious and sac-like, but sometimes, as in Chimaera, may be hardly distinct from the rest of the alimentary canal. No diverticulum filled with air, and constituting a swimming-bladder, as in Ganoid and many Teleostean fishes, is connected with either the oesophagus, or the stomach, though a rudiment of this structure has lately been discovered in some Elasmobranchs.

The intestine is short, and usually commences by a dilatation separated from the stomach by a pyloric valve. This duodenal segment of the intestine is usually known as the Bursa Entiana. It receives the hepatic and pancreatic ducts, and, in the foetus, the vitelline duct. Beyond this part, the absorptive area of the mucous membrane of the small intestines is increased by the production of that membrane into a fold, the so-called spiral valve, the fixed edge of which usually runs spirally along the wall of the intestine. In some sharks (Carcharias, Galeocerdo) the fixed edge of the fold runs straight and parallel with the axis of the intestine, and the fold is rolled up upon itself into a cylindrical spiral.

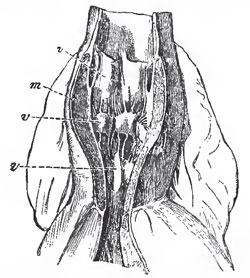

|

| Fig. 35.-The aortic bulb of a Shark (Lamna), laid open to show the three rove of valves, v, v, v, and the thick muscular wall, m. |

The short rectum terminates in the front part of a cloaca, which is common to it and the ducts of the renal and the reproductive organs. The peritoneal cavity communicates with that of the pericardium in front, and, behind, opens externally by two abdominal pores. The heart presents a single auricle, receiving the venous blood of the body from a sinus venosus. There is a single ventricle, and the walls of the aortic bulb contain striped muscular fibres, and are rhythmically contractile, pulsating as regularly as those of the auricle and ventricle.

The interior of the bulb exhibits not merely a single row of valves at the ventriculo-bulbous aperture, but several other transverse rows of semilunar valves, which are attached to the walls of the bulb itself, and at its junction with the aorta. These valves must be of great importance in giving full effect to the propulsive force exerted by the muscular wall of the bulb.

In a good many Elasmobranchii there is a spiracle, or aperture leading into the cavity of the mouth, on the upper side of the head, in front of the suspensorium. From this aperture (which, according to the observations of Prof. Wyman, is the remains of the first visceral cleft of the embryo, as well as from the proper branchial clefts, long branchial filaments protrude, in the foetal state. These disappear in the adult, the respiratory organs of which are flattened pouches, with traversely-plaited walls, from five to seven in number. They open by external clefts upon the sides (Sharks and Chimaera), or under-surface (Rays), of the neck, and, by internal apertures, into the pharynx.

The anterior wall of the anterior sac is supported by the hyoidean arch. Between the posterior wall of the first, and the anterior wall of the second sac, and between the adjacent walls of the other sacs, a branchial arch with its radiating cartilages is interposed. Hence the hyoidean arch supports one series of branchial plates or laminae; while the succeeding branchial arches, except the last, bear two series, separated by a septum, consisting of the adjacent walls of two sacs with the interposed branchial skeleton.

The cardiac aorta, a trunk which is the continuation of the bulb of the aorta, distributes the blood to the vessels of these sacs; and it is there aerated by the water which is taken in at the mouth and forced through the pharyngeal apertures, outward.

The kidneys of the Elasmobranchii do not extend so far forward as those of most other fishes. The ureters generally become dilated near their terminations, and open by a common urinary canal into the cloaca behind the rectum.

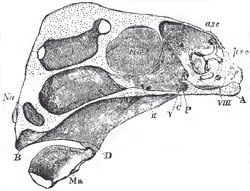

The brain is well developed. It usually presents a large cerebellum, overlying the fourth ventricle, the side-walls of which (corpora restiformia) are singularly folded (Fig. 37, A., a); and moderate-sized optic lobes, which are quite distinct from the conspicuous thalamencephalon, or vesicle of the third ventricle. The third ventricle itself is a relatively wide and short cavity, which sends a prolongation forward, on each side, into a large, single, transversely-elongated mass (Fig. 37, a), which is usually regarded as the result of the coalescence of the cerebral hemispheres, but is perhaps, more properly, to be considered as the thickened termination of the primitive encephalon, in which the lamina terminalis and the hemispheres are hardly differentiated. The large olfactory lobes are usually prolonged into pedicles, which dilate into great ganglionic masses where they come into contact with the olfactory sacs (Fig. 37, A., s). The latter always open upon the under-surface of the head. A cleft, which extends from each nasal aperture to the margin of the gape, is the remains of the embryonic separation between the naso-frontal process and the maxillopalatine process, and represents the naso-palatine passage of the higher vertebrata. The optic nerves fuse into a complete chiasma (Fig. 37, B, ch), as in the higher Vertebrata. In some Sharks, the eye is provided with a third eyelid or nictitating membrane, moved by a single muscle, or by two muscles, arranged in a manner somewhat similar to that observed in birds. In both Sharks and Rays, the posterior surface of the sclerotic presents an eminence which articulates with the extremity of a cartilaginous stem proceeding from the bottom of the orbit.

Except in Chimaera, the labyrinth is completely enclosed in cartilage. In the Rays, the anterior and posterior "semicircular" canals are circular, and open by distinct narrow ducts into the vestibular sac. In the other Elasmobranchii they are arranged in the ordinary way. A passage, leading from the vestibular sac to the top of the skull, and opening there by a valvular aperture, represents the canal by which, in the vertebrate embryo, the auditory involution of the integument is at first connected with the exterior.

The testes are oval, and are provided with an epididymis and vas deferens, as in the higher Vertebrata. The vas deferens of each side opens into the dilated part of the ureter. Attached to the ventral fins of the male are peculiar appendages, termed claspers.

The ovaria are rounded, solid organs. There are usually two, but in some cases, as in the Dogfishes and nictitating Sharks, the ovary is single and symmetrical. The oviducts are true Fallopian tubes, which communicate freely with the abdominal cavity at their proximal ends. Distally, they dilate into uterine chambers, which unite and open into the cloaca.

The eggs are very large, and comparatively few.

The Dogfishes, the Rays, and the Chimaera, are oviparous, and lay eggs, enclosed in hard, leathery cases; the others are viviparous, and, in certain species of Mustelus (laevis) and Carcharias, a rudimentary placenta is formed, the vascular walls of the umbilical sac becoming plaited, and interdigitating with similar folds of the wall of the uterus.

The embryos of most Elasmobranchs are, at first, provided with long external branchial filaments, which proceed from the periphery of the spiracle, as well as from most of the branchial arches. These disappear, and are functionally replaced by internal gills as development advances.

The Elasmobranchii are divided into two groups, the Holocephali and the Plagiostomi.

In the Holocephali, the palato-quadrate and suspensorial cartilages are united with one another and with the skull into a continuous cartilaginous plate; the branchial clefts are covered by an opercular membrane. The teeth are very few in number (not more than six, four of which are in the upper, and two in the lower jaw, in the living species), and differ in structure from those of the Plagiostomi. This sub-order contains the living Chimaera and Callorhynchus, the extinct Mesozoic Edaphodon and Passalodon; and, very probably, some of the more ancient Elasmobranchs, the teeth of which are so abundant in the Carboniferous limestones.

In the Plagiostomi, the palato-quadrate and suspensorial cartilages are distinct from one another, and are movable upon the skull. The branchial clefts are not covered by any opercular membrane. The teeth are usually numerous.

The Plagiostomi are again subdivided into the Sharks (Selachii or Squali), with the branchial apertures at the sides of the body, the anterior ends of the pectoral fins not connected with the skull by cartilages, and the skull with a median facet for the first vertebra; and the Rays (Rajae), with the branchial clefts on the under-surface of the body, the pectoral fins united by cartilages to the skull, and no median articular facet upon the occiput for the first vertebra.

The Elasmobranchii are essentially marine in their habits; though Sharks are said to occur very high up in some of the great rivers of South America.

Both divisions of the Plagiostomi occur in the Mesozoic rocks. In the Palaeozoic epoch, dermal defences and teeth of Elasmobranchii abound in the Permian and Carboniferous formations, and are met with in the Upper Silurian rocks. But, except in the case of Pleuracanthus (a Selachian), it is impossible to be certain to what special divisions they belong.