The Pharyngobranchii

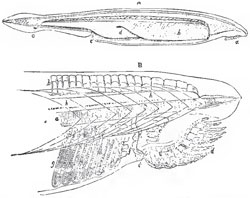

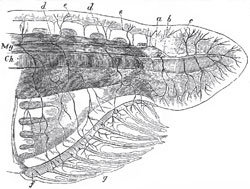

This order contains but one species of fish, the remarkable Lancelet, or Amphioxus lanceolatus, which lives in sand, at moderate depths in the sea, in many parts of the world. It is a small, semitransparent creature, pointed at both ends, as its name implies, and possessing no limbs, nor any hard epidermic or dermal covering.The dorsal and caudal regions of the body present a low median fold of integument, which is the sole representative of the system of the median fins of other fishes. The mouth (Fig. 28, A, a) is a proportionally large oval aperture, which lies behind, as well as below, the anterior termination of the body, and has its long axis directed longitudinally. Its margins are produced into delicate ciliated tentacles, supported by semi-cartilaginous filaments, which are attached to a hoop of the same texture placed around the margins of the mouth (Fig. 29, f, g). These probably represent the labial cartilages of other fishes. The oral aperture leads into a large and dilated pharynx, the walls of which are perforated by numerous clefts, and richly ciliated, so that it resembles the pharynx of an Ascidian (Fig-28, B, f, g). This great pharynx is connected with a simple gastric cavity which passes into a. straight intestine, ending in the anal aperture, which is situated at the root of the tail at a little to the left of the median line (Fig. 28, A, c). The mucous membrane of the intestine is ciliated.

The liver (Fig. 28, A, d) is a saccular diverticulum of the ntestine, the apex of which is turned forward.

The existence of distinct kidneys is doubtful; and the reproductive organs are simply quadrate glandular masses, attached in a row, on each side of the walls of the visceral cavity, into which, when ripe, they pour their contents.

The heart retains the tubular condition which it possesses in the earliest embryonic stage only, in other Vertebrata. The blood brought back from the body and from the alimentary canal enters a pulsatile cardiac trunk, which runs along the middle of the base of the pharynx, and sends branches up on each side. The two most anterior of these pass directly to the dorsal aorta; the others enter into the ciliated bars which separate the branchial slits, and, therefore, are so many branchial arteries. Contractile dilatations are placed at the bases of these branchial arteries. On the dorsal side of the pharynx the blood is poured, by the two anterior trunks, and by the branchial veins which carry away the aerated blood from the branchial bars, into a great longitudinal trunk, or dorsal aorta, by which it is distributed throughout the body.

The skeleton is in an extremely rudimentary condition, the spinal column being represented by a notochord, which extends throughout the whole length of the body, and terminates, at each extremity, in a point (Fig. 28). The investment of the notochord is wholly membranous, as are the boundary-walls of the neural and visceral chambers, so that there is no appearance of vertebral centra, arches, or ribs. A longitudinal series of small semi-cartilaginous rod-like bodies, which lie above the neural canal, represent either neural spines or fin-rays (Fig. 38, B, b). Neither is there a trace of any distinct skull, jaws, or hyoidean apparatus; and, indeed, the neural chamber, which occupies the place of the skull, has a somewhat smaller capacity than a segment of the spinal canal of equal length.

There are no auditory organs, and it is doubtful if a ciliated sac, which exists in the middle line, at the front part of the cephalic region (Fig. 29, a), ought to be considered as an olfactory organ.

The myelon traverses the whole length of the spinal canal, and ends anteriorly without enlarging into a brain. From its rounded termination nerves are given off to the oral region, and to the rudimentary eye or eyes (Fig. 26, b, c).

According to M. Kowalewsky, ("Memoires de I' Academie Imperiale des Sciences de St. Petersburg," 1867) who has recently studied the development of Amphioxus, the vitellus undergoes complete segmentation, and is converted into a hollovv sphere, the walls of which are formed of a single layer of nucleated cells. The wall of the one moiety of the sphere is next pushed in, as it were, until it comes into contact with the other, thus reducing the primitive cavity to nothing, but giving rise to a secondary cavity, surrounded by a double membrane. The operation is, in substance, just the same as that by which a double nightcap is made fit to receive the head. The blastoderm now acquires cilia, and becomes nearly spherical again, the opening into the secondary cavity being reduced to a small aperture at one pole, which eventually becomes the anus. M. Kowalewsky points out the resemblance, amounting almost to identity, of the embryo at this stage with that of many Invertebrata.

One face of the spheroidal blastoderm becomes flattened, and gives rise to laminae dorsales, which unite in the characteristically vertebrate fashion; and the notochord appears between and below them, and very early extends forward beyond the termination of the neural canal. The neural canal remains in communication with the exterior, for a long time, by a minute pore at its anterior extremity. The mouth arises as a circular aperture, developed upon the right side of the anterior end of the body, by the coalescence of the two layers of the blastoderm, and the subsequent perforation of the disk formed by this coalescence. The branchial apertures arise by a similar process which takes place behind the mouth; and they are, at first, completely exposed on the surface of the body. But, before long, a longitudinal fold is developed upon each side, and grows over the branchial apertures. The two folds eventually coalesce on the ventral side, leaving only the abdominal pore open. One cannot but be struck with the resemblance of these folds to the processes of integument which grow over the branchiae of the amphibian larva; and, in like manner, enclose a cavity which communicates with the exterior only by a single pore.

In a great many of the characters which have been enumerated-as, for example, in the entire absence of a distinct skull and brain, of auditory organs, of kidneys, of a chambered heart; in the presence of a saccular liver, of ciliated branchiae and alimentary canal; and in the extension of the notochord forward to the anterior end of the body-Amphioxus differs from every other vertebrated animal. Hence Prof. Haeckel has proposed to divide the Vertebrata into two primary groups-the Leptocardia, containing Amphioxus; and the Pachycardia, comprising all other Vertebrata. The great peculiarities in the development of Amphioxus, and the many analogies with invertebrate animals, particularly the Ascidians, which it presents, lend much support to this proposition. No fossil form allied to Amphioxus is known.