The Skull

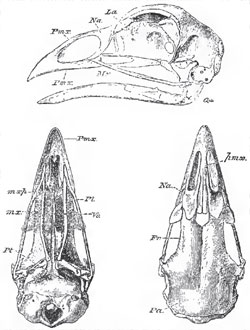

In the bird's skull (Fig. 82), the brain-case is more arched and spacious, and is larger, in proportion to the face, than in any Reptilia, with the exception of the Pterosauria. There is a well-marked interorbital septum, but the extent to which it is ossified varies greatly. As a general rule, the superior temporal bar is incomplete, and there is no distinct post-frontal bone. The inferior temporal bar, formed by the jugal and quadrato-jugal, on the other hand, is always complete. There are no long parotic processes, nor any post-temporal fossae, the whole of each parietal bone being, as it were, absorbed in the roof of the skull.The nasal apertures are almost always situated far back near the base of the beak. In the dry skull (above Mx. in Fig. 82), there is a lachrymo-nasal fossa, or interval unoccupied by bone, between the nasal, lachrymal, and maxillary bones, such as exists in some Teleosauria, Dinosauria, and Pterosauria.

The posterior nares lie between the palatines and the vomer; and the nasal passage is never separated from the cavity of the mouth by the union of palatine plates of the palatine or pterygoid bones.

The bones of the brain-case, and most of those of the face, very early become anchylosed together into an indistinguish able whole in most birds, but the sutures remain distinguishable longer in the Chenomorphae and Spheniscomorphae; and especially in the Ratitae.

All the constituents of the occipital and parietal segments of the skull are represented by distinct bones, but the frontal segment varies a good deal in this respect. The basisphenoid has a long rostrum, which represents part of the parasphenoid of the Ichthyopsida. Large frontal bones always exist, but the pre-sphenoidal and orbito-sphenoidal regions are not so regularly ossified.

The ethmoid is ossified and frequently appears upon the surface of the skull, between the nasal and the frontal bones; and the internasal septum, in front of the ethmoid, may present very various degrees of ossification. Very frequently, the interspace between the ethmoidal and the internasal ossifications is simply membranous in the adult, and the beak is held to the skull only by the ascending processes of the premaxillary bones, and by the nasal bones, which are thin and flexible. By this means a sort of elastic joint is established, conferring upon the beak a certain range of vertical motion. In the Parrots, and some other birds, this joint is converted into a true articulation, and the range of motion of the upper beak becomes very extensive.

The periotic capsule is completely ossified, and, as in other Sauropsida, the epiotic and the opisthotic are anchylosed with the occipital segment before they unite with the prootic. In the primordial skull of the bird the olfactory organs are surrounded by cartilaginous capsules, the lateral walls of which send in turbinal processes of very various degrees of complexity. When the posterior wall of this capsule is ossified, the boue thus formed represents the prefrontal, or lateral mass of the ethmoid, of the mammal. It is largely developed in the Apteryx, in the Casuaridae, and many other birds, but is absent in the Struthionidae; and, in other birds, is often represented by a mere bar of bone standing out from the ethmoidal ossification.

|

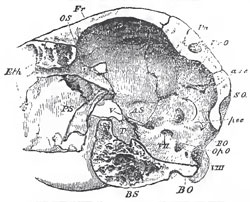

| Fig. 83. - A longitudinal and vertical section of the posterior half of the skull of an Ostrich P., the pituitary fossa; asc, psc, anterior and posterior vertical semicircular canals of the ear. |

The squamosal is closely applied to the skull, and is, usually, anchylosed with the other bones. It often sends a process downward over the quadrate bone, and it may be united by bone with the post-orbital process of the frontal, as in the Fowl.

The frame of the tympanic membrane not unfrequently contains distinct ossifications, which represent the tympanic bone of the Mammalia.

|

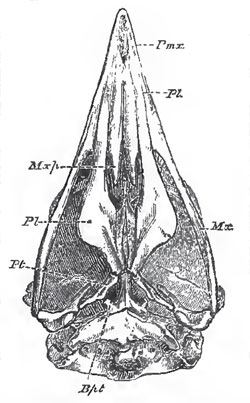

| Fig. 84. - The under surface of the cramum of the Secretary bird (Gypogeranus). as an example

of the Dosmognathous arrangement. Mxp., maxillo-palatine process; Bpt, bbsl pterygoid processes. |

The vomers vary more than almost any other bones of the skull. They underlie and embrace the inferior edge of the ethmo-presphenoidal region of the basis cranii, and, in all birds in which they are distinctly developed, except the Ostrich, they are connected behind with the palatine bones. In most birds, they early unite into a single bone; but they remain long distinct in some Coracomorphoe, and seem to be always separate in the Woodpeckers. The coalesced vomers constitute a very large and broad bone in most Ratitae, and in the Tinamomorphae; a narrow elongated bone pointed in front in Schizognathae; a broad bone deeply cleft behind, and abruptly truncated in front, in Coracomorphae. In most Desmognathae the vomer is small; and, sometimes, it appears to be obsolete.

The maxillae of birds are usually slender, rod-like bones, articulating by squamous suture, in front, with the premaxillae, and, behind, with the equally slender jugals. In the great majority of birds the maxilla sends inward a maxillo-palatine process (Fig. 83, mxp.), which, sometimes, is mere thin lamella of bone, sometimes, becomes swollen and spongy. In the Ratitae and the Desmognathae (Fig. 84), the maxillo-palatine processes unite with the vomer, or with one another, and form a complete bony roof across the palate. In the Schizognathae (Fig. 82), and Aegithognathae, the maxillo-palatines remain quite distinct both from one another and from the vomer.

The quadrato-jugal is usually a slender rod of bone, the hinder extremity of which presents, on its inner side, an articular head which fits into a fossa in the outer face of the distal end of the quadrate bone.