Characteristics of Reptiles that Distinguish Them from Amphibians

Characteristics

of Reptiles That

Distinguish Them

from Amphibians

-

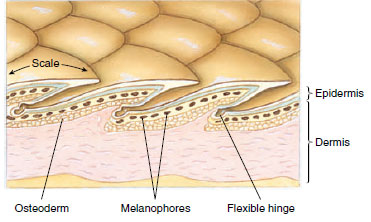

Reptiles have tough, dry, scaly skin offering protection against desiccation and physical injury. The skin consists of a thin epidermis, shed periodically, and a much thicker, well-developed dermis (Figure 28-3). The dermis is provided with chromatophores, colorbearing cells that give many lizards and snakes their colorful hues. This layer, unfortunately for their bearers, is converted into alligator and snakeskin leather, so esteemed for expensive pocketbooks and shoes. The characteristic scales of reptiles are formed largely of keratin. They are derived mostly from the epidermis and thus are not homologous to fish scales, which are bony, dermal structures. In some reptiles, such as alligators, the scales remain throughout life, growing gradually to replace wear. In others, such as snakes and lizards, new scales grow beneath the old, which are then shed at intervals. Turtles add new layers of keratin under the old layers of the platelike scutes, which are modified scales. In snakes the old skin (epidermis and scales) is turned inside out when discarded; lizards split out of the old skin leaving it mostly intact and right side out, or it may slough off in pieces. Crocodiles and many lizards possess bony plates called osteoderms located beneath the keratinized scale.

Figure 28-3

Section of the skin of a reptile showing the overlapping

epidermal scales.

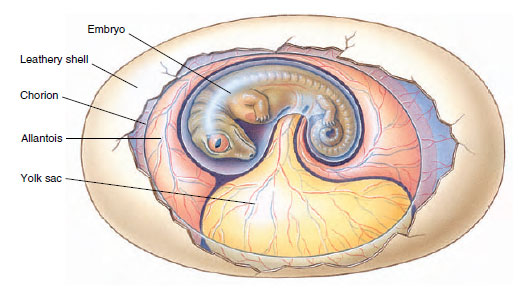

- The shelled (amniotic) egg of reptiles contains food and protective membranes for supporting embryonic development on land. Reptiles lay their eggs in sheltered locations on land. The young hatch as lung-breathing juveniles rather than as aquatic larvae. The appearance of the shelled egg (Figure 28-4) widened the division between evolving amphibians and reptiles and, probably more than any other adaptation, contributed to the evolutionary establishment of reptiles.

- Reptilian jaws are efficiently designed for applying crushing or gripping force to prey. The jaws of fish and amphibians are designed for quick jaw closure, but once the prey is seized, little static force can be applied. In reptiles, jaw muscles became larger, longer, and arranged for much better mechanical advantage.

- Reptiles have some form of copulatory organ, permitting internal fertilization. Internal fertilization is obviously a requirement for a shelled egg, because sperm must reach the egg before the egg is enclosed. Sperm from the paired testes are carried by the vasa deferentia to the copulatory organ, which is an evagination of the cloacal wall. The female system consists of paired ovaries and oviducts. Glandular walls of the oviducts secrete albumin (source of amino acids, minerals, and water for the embryo) and shells for the large eggs.

- Reptiles have an efficient circulatory system and higher blood pressure than amphibians. In all reptiles the right atrium, which receives unoxygenated blood from the body, is completely partitioned from the left atrium, which receives oxygenated blood from the lungs. Crocodilians have two completely separated ventricles as well (Figure 28-5); in other reptiles the ventricle is incompletely separated. Even in reptiles with incomplete separation of the ventricles, flow patterns within the heart prevent admixture of pulmonary (oxygenated) and systemic (unoxygenated) blood; all reptiles therefore have two functionally separate circulations.

- Reptilian lungs are better developed than those of amphibians. Reptiles depend almost exclusively on lungs for gas exchange, supplemented by respiration through pharyngeal membranes in some aquatic turtles. Unlike the amphibians, which force air into the lungs with mouth muscles, the reptiles suck air into the lungs by enlarging the thoracic cavity, either by expanding the rib cage (snakes and lizards) or by movement of internal organs (turtles and crocodilians). Reptiles have no muscular diaphragm, a structure found only in mammals. Cutaneous respiration (gas exchange across the skin), so important to amphibians, has been abandoned by reptiles.

- Reptiles have evolved efficient strategies for water conservation. All amniotes have a metanephric kidney, which is drained by its own passageway, the ureter. However, the nephrons of the reptilian metanephros lack the specialized intermediate section of the tubule, the loop of Henle, which enables the kidney to concentrate solutes in the urine. Many reptiles have salt glands located near the nose or eyes (in the tongue of saltwater crocodiles), which secrete a salty fluid that is strongly hyperosmotic to the body fluids. Nitrogenous wastes are excreted as uric acid, rather than urea or ammonia. Uric acid has a low solubility and precipitates out of solution readily, allowing water to be conserved; the urine of many reptiles is a semisolid suspension.

- All reptiles, except limbless members, have better body support than amphibians and more efficiently designed limbs for travel on land. Nevertheless, most modern reptiles walk with their legs splayed outward and their belly close to the ground. Most dinosaurs, however, (and some modern lizards) walked on upright legs held beneath the body, the best arrangement for rapid movement and for the support of body weight. Many dinosaurs walked on powerful hindlimbs alone.

- The reptilian nervous system is considerably more complex than the amphibian. Although the reptile’s brain is small, the cerebrum is larger relative to the rest of the brain. The crocodilians have the first true cerebral cortex (neopallium). Connections to the central nervous system are more advanced, permitting complex behaviors unknown in amphibians. With exception of hearing, sense organs in general are well developed. Jacobson’s organ, a specialized olfactory chamber present in many tetrapods, is highly developed in lizards and snakes. Odors are carried to Jacobson’s organ by the tongue.

|

| Figure 28-4 Amniotic egg. The embryo develops within the amnion and is cushioned by amniotic fluid. Food is provided by yolk from the yolk sac and metabolic wastes are deposited within the allantois. As development proceeds, the allantois fuses with the chorion, a membrane lying against the inner surface of the shell; both membranes are supplied with blood vessels that assist in the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide across the porous shell. Because this kind of egg is an enclosed, selfcontained system, it is often called a “cleidoic” egg (Gr. kleidoun, to lock in). |

|

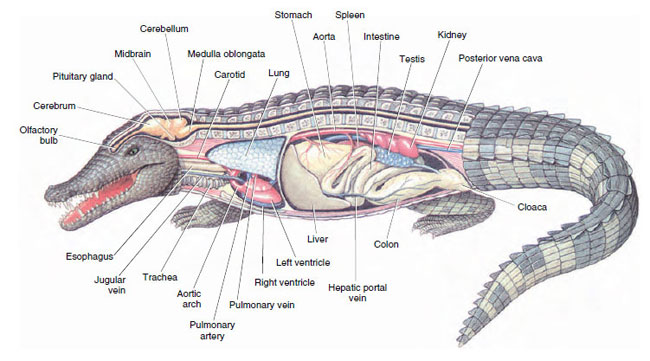

| Figure 28-5 Internal structure of a male crocodile. |