Darwin's Theory of Evolution

Darwin's theory of evolution is now over 130 years old (Organic Evolution). Darwin articulated the complete theory when he published his famous book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection in England in 1859 (Figure 1- 12). Biologists today are frequently asked, “What is Darwinism?” and “Do biologists still accept Darwin's theory of evolution?” These questions cannot be given simple answers, because Darwinism encompasses several different, although mutually compatible, theories. Professor Ernst Mayr of Harvard University has argued that Darwinism should be viewed as five major theories.* These five theories have somewhat different origins and different fates and cannot be discussed accurately as if they were only a single statement. The theories are (1) perpetual change, (2) common descent, (3) multiplication of species, (4) gradualism, and (5) natural selection. The first three theories are generally accepted as having universal application throughout the living world. The theories of gradualism and natural selection are controversial among evolutionists, although both are strongly advocated by a large portion of the evolutionary community and are important components of the Darwinian evolutionary paradigm. Gradualism and natural selection are clearly part of the evolutionary process, but their explanatory power might not be as widespread as Darwin intended. Legitimate controversies regarding gradualism and natural selection often are misrepresented by creationists as challenges to the first three theories presented above, although the validity of those first three theories is strongly supported by all relevant observations.

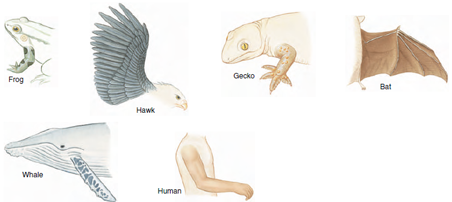

Natural selection explains why organisms are constructed to meet the demands of their environments, a phenomenon called adaptation (Figure 1-15). Adaptation is the expected result of a process that accumulates the most favorable variants occurring in a population throughout long periods of evolutionary time. Adaptation was viewed previously as strong evidence against evolution, and Darwin's theory of natural selection was therefore important for convincing people that a natural process, capable of being studied scientifically, could produce new species. The demonstration that natural processes could produce adaptation was important to the eventual acceptance of all five Darwinian theories.

Darwin's theory of natural selection faced a major obstacle when it was first proposed: it lacked a theory of heredity. People assumed incorrectly that heredity was a blending process, and that any favorable new variant appearing in a population therefore would be lost. The new variant arises initially in a single organism, and that organism therefore must mate with one lacking the favorable new trait. Under blending inheritance, the organism's offspring would then have only a diluted form of the favorable trait. These offspring likewise would mate with others that lack the favorable trait. With its effects diluted by half each generation, the trait eventually would cease to exist. Natural selection would be completely ineffective in this situation.

Darwin was never able to counter this criticism successfully. It did not occur to Darwin that hereditary factors could be discrete and nonblending and that a new genetic variant therefore could persist unaltered from one generation to the next. This principle is known as particulate inheritance. It was established after 1900 with the discovery of Gregor Mendel's genetic experiments, and it was eventually incorporated into what we now call the chromosomal theory of inheritance. We use the term neo-Darwinism to describe Darwin's theories as modified by incorporating this theory of inheritance.

- Perpetual change.

This is the basic theory of evolution on which the others are based. It states that the living world is neither constant nor perpetually cycling, but is always changing. The properties of organisms undergo transformation across generations throughout time. This theory originated in antiquity but did not gain widespread acceptance until Darwin advocated it in the context of his other four theories. “Perpetual change” is documented by the fossil record, which clearly refutes creationists' claims for a recent origin of all living forms. Because it has withstood repeated testing and is supported by an overwhelming number of observations, we now regard “perpetual change” as a scientific fact. - Common descent.

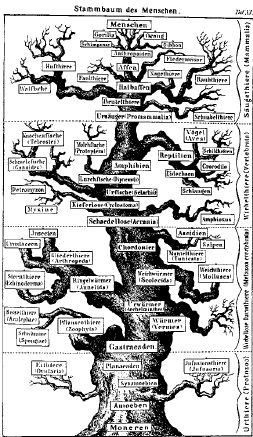

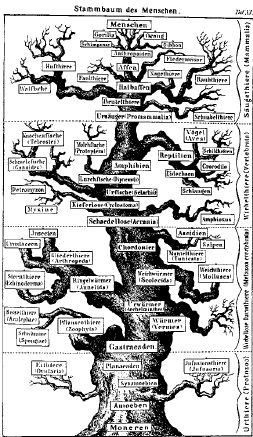

The second Darwinian theory, “common descent,” states that all forms of life descended from a common ancestor through a branching of lineages (Figure 1-13). The opposing argument, that the different forms of life arose independently and descended to the present in linear, unbranched genealogies, has been refuted by comparative studies of organismal form, cell structure, and macromolecular structures (including those of the genetic material, DNA). All of these studies confirm the theory that life's history has the structure of a branching evolutionary tree, known as a phylogeny. Species that share relatively recent common ancestry have more similar features at all levels than do species that have only an ancient common ancestry. Much current research is guided by Darwin's theory of common descent toward reconstructing life's phylogeny using the patterns of similarity and dissimilarity observed among species. The resulting phylogeny serves as the basis for our taxonomic classification of animals (Classification and Phylogeny of Animals). - Multiplication of species.

Darwin's third theory states that the evolutionary process produces new species by the splitting and transformation of older ones. Species are now generally viewed as reproductively distinct populations of organisms that usually but not always differ from each other in organismal form. Once species are fully formed, interbreeding among members of different species does not occur. Evolutionists generally agree that the splitting and transformation of lineages produces new species, although there is still much controversy concerning the details of this process (Organic Evolution) and the precise meaning of the term “species” (Classification and Phylogeny of Animals). The study of the historical processes that generate new species guides much active scientific research. - Gradualism.

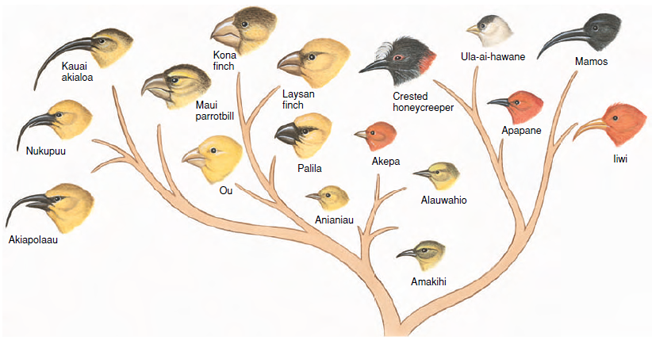

Gradualism states that the large differences in anatomical traits that characterize different species originate through the accumulation of many small incremental changes over very long periods of time. This theory is important because genetic changes having very large effects on organismal form are usually harmful to the organism. It is possible, however, that some genetic variants that have large effects on the organism are nonetheless sufficiently beneficial to be favored by natural selection. Therefore, although gradual evolution is known to occur, it may not explain the origin of all structural differences that we observe among species (Figure 1-14). Scientists are still actively studying this question. - Natural selection.

Natural selection, Darwin's most famous theory, rests on three propositions. First, there is variation among organisms (within populations) for anatomical, behavioral, and physiological traits. Second, the variation is at least partly heritable so that offspring tend to resemble their parents. Third, organisms with different variant forms leave different numbers of offspring to future generations. Variants that permit their possessors most effectively to exploit their environments will preferentially survive and be transmitted to future generations. Over many generations, favorable new traits will spread throughout the population. Accumulation of such changes leads, over long periods of time, to the production of new organismal features and new species. Natural selection is therefore a creative process that generates novel features from the small individual variations that occur among organisms within a population.

Figure 1-13 An early tree of life drawn in 1874 by the German biologist, Ernst Haeckel, who was strongly influenced by Darwin's theory of common descent. Many of the phylogenetic hypotheses shown in this tree, including the unilateral progression of evolution toward humans (Menschen, top), have since been refuted.

Figure 1-13 An early tree of life drawn in 1874 by the German biologist, Ernst Haeckel, who was strongly influenced by Darwin's theory of common descent. Many of the phylogenetic hypotheses shown in this tree, including the unilateral progression of evolution toward humans (Menschen, top), have since been refuted.

Figure 1-14 Gradualism provides a plausible explanation for the origin of different bill shapes in the Hawaiian honeycreepers shown here. This theory has been challenged, however, as an explanation of the evolution of such structures as vertebrate scales, feathers, and hair from a common ancestral structure. The geneticist Richard Goldschmidt viewed the latter forms as unbridgeable by any gradual transformation series.

Natural selection explains why organisms are constructed to meet the demands of their environments, a phenomenon called adaptation (Figure 1-15). Adaptation is the expected result of a process that accumulates the most favorable variants occurring in a population throughout long periods of evolutionary time. Adaptation was viewed previously as strong evidence against evolution, and Darwin's theory of natural selection was therefore important for convincing people that a natural process, capable of being studied scientifically, could produce new species. The demonstration that natural processes could produce adaptation was important to the eventual acceptance of all five Darwinian theories.

Darwin's theory of natural selection faced a major obstacle when it was first proposed: it lacked a theory of heredity. People assumed incorrectly that heredity was a blending process, and that any favorable new variant appearing in a population therefore would be lost. The new variant arises initially in a single organism, and that organism therefore must mate with one lacking the favorable new trait. Under blending inheritance, the organism's offspring would then have only a diluted form of the favorable trait. These offspring likewise would mate with others that lack the favorable trait. With its effects diluted by half each generation, the trait eventually would cease to exist. Natural selection would be completely ineffective in this situation.

Darwin was never able to counter this criticism successfully. It did not occur to Darwin that hereditary factors could be discrete and nonblending and that a new genetic variant therefore could persist unaltered from one generation to the next. This principle is known as particulate inheritance. It was established after 1900 with the discovery of Gregor Mendel's genetic experiments, and it was eventually incorporated into what we now call the chromosomal theory of inheritance. We use the term neo-Darwinism to describe Darwin's theories as modified by incorporating this theory of inheritance.