Feeding on Particulate Matter

Feeding on Particulate

Matter

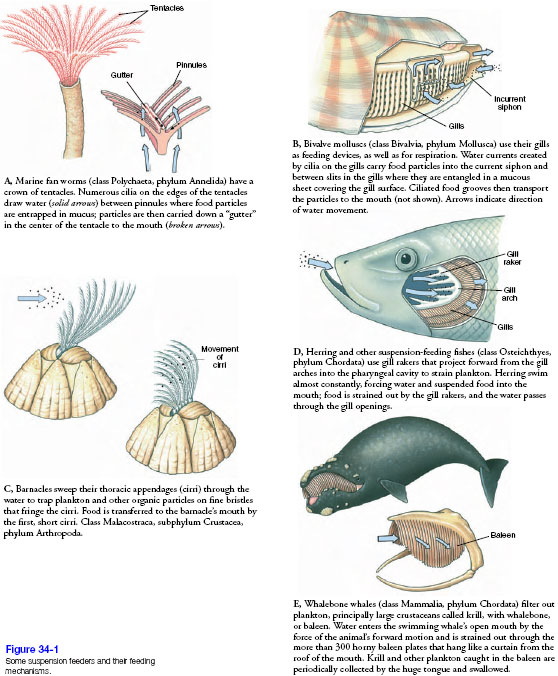

Drifting microscopic particles are found in the upper hundred meters of the ocean. Most of this multitude is plankton, organisms too small to do anything but drift with the ocean’s currents. The rest is organic debris, the disintegrating remains of dead plants and animals. Although this oceanic swarm of plankton forms a rich life domain, it is unevenly distributed. The heaviest plankton growth occurs in estuaries and areas of upwelling, where there is an abundant nutrient supply. It is consumed by numerous larger animals, invertebrates and vertebrates, using a variety of feeding mechanisms. One of the most important and widely employed methods for feeding is suspension feeding (Figure 34-1). The majority of suspension feeders use ciliated surfaces to produce currents that draw drifting food particles into their mouths. Most suspension-feeding invertebrates, such as tube-dwelling polychaete worms, bivalve molluscs, hemichordates, and most protochordates, entrap particulate food on mucous sheets that convey the food into the digestive tract. Others, such as fairy shrimps, water fleas, and barnacles, use sweeping movements of their setae-fringed legs to create water currents and entrap food, which is transferred to the mouth. In freshwater developmental stages of certain insect orders, the organisms use fanlike arrangements of setae or spin silk nets to entrap food.

One form of suspension feeding, often called filter feeding, has evolved frequently as a secondary modification among representatives of groups that are primarily selective feeders. Examples are many of the microcrustaceans, fishes such as herring, menhaden, and basking sharks, certain birds such as flamingos, and the largest of all animals, baleen (whalebone) whales. The vital importance of one component of plankton, the diatoms, in supporting a great pyramid of suspension-feeding animals is stressed by N. J. Berrill:*

A humpback whale . . . needs a ton of herring in its stomach to feel comfortably full—as many as five thousand individual fish. Each herring, in turn, may well have 6000 or 7000 small crustaceans in its own stomach, each of which contains as many as 130,000 diatoms. In other words, some 400 billion yellowgreen diatoms sustain a single medium-sized whale for a few hours at most.

Another type of particulate feeding exploits deposits of disintegrated organic material (detritus) that accumulates on and in the substratum; this type is called deposit feeding. Some deposit feeders, such as many annelids and some hemichordates, simply pass the substrate through their bodies, removing from it whatever provides nourishment. Others, such as scaphopod molluscs, certain bivalve molluscs, and some sedentary and tube-dwelling polychaete worms, use appendages to gather organic deposits some distance from the body and move them toward the mouth (Figure 34-2).

Drifting microscopic particles are found in the upper hundred meters of the ocean. Most of this multitude is plankton, organisms too small to do anything but drift with the ocean’s currents. The rest is organic debris, the disintegrating remains of dead plants and animals. Although this oceanic swarm of plankton forms a rich life domain, it is unevenly distributed. The heaviest plankton growth occurs in estuaries and areas of upwelling, where there is an abundant nutrient supply. It is consumed by numerous larger animals, invertebrates and vertebrates, using a variety of feeding mechanisms. One of the most important and widely employed methods for feeding is suspension feeding (Figure 34-1). The majority of suspension feeders use ciliated surfaces to produce currents that draw drifting food particles into their mouths. Most suspension-feeding invertebrates, such as tube-dwelling polychaete worms, bivalve molluscs, hemichordates, and most protochordates, entrap particulate food on mucous sheets that convey the food into the digestive tract. Others, such as fairy shrimps, water fleas, and barnacles, use sweeping movements of their setae-fringed legs to create water currents and entrap food, which is transferred to the mouth. In freshwater developmental stages of certain insect orders, the organisms use fanlike arrangements of setae or spin silk nets to entrap food.

|

| Figure 34-1 Some suspension feeders and their feeding mechanisms. |

One form of suspension feeding, often called filter feeding, has evolved frequently as a secondary modification among representatives of groups that are primarily selective feeders. Examples are many of the microcrustaceans, fishes such as herring, menhaden, and basking sharks, certain birds such as flamingos, and the largest of all animals, baleen (whalebone) whales. The vital importance of one component of plankton, the diatoms, in supporting a great pyramid of suspension-feeding animals is stressed by N. J. Berrill:*

A humpback whale . . . needs a ton of herring in its stomach to feel comfortably full—as many as five thousand individual fish. Each herring, in turn, may well have 6000 or 7000 small crustaceans in its own stomach, each of which contains as many as 130,000 diatoms. In other words, some 400 billion yellowgreen diatoms sustain a single medium-sized whale for a few hours at most.

Another type of particulate feeding exploits deposits of disintegrated organic material (detritus) that accumulates on and in the substratum; this type is called deposit feeding. Some deposit feeders, such as many annelids and some hemichordates, simply pass the substrate through their bodies, removing from it whatever provides nourishment. Others, such as scaphopod molluscs, certain bivalve molluscs, and some sedentary and tube-dwelling polychaete worms, use appendages to gather organic deposits some distance from the body and move them toward the mouth (Figure 34-2).