Phylum Nemertea (Rhynchocoela)

Phylum Nemertea

(Rhynchocoela)

Nemerteans (nem-er´te-ans) (Gr. Nemertes, one of the Nereids, unerring one) are often called ribbon worms. Their name refers to the unerring aim of the proboscis, a long muscular tube (Figures 14-23 and 14-24). The phylum is also called Rhynchocoela (ring´kose ´la) (Gr. rhynchos, beak, + koilos, hollow), which also refers to the proboscis. They are thread-shaped or ribbon-shaped worms; nearly all are marine. Some live in secreted gelatinous tubes. There are about 650 species in the group.

Nemertean worms are usually less

than 20 cm long, although a few are

several meters in length (Figure 14-25). Lineus longissimus (L. linea, line) is

said to reach 30 m. Their colors are

often bright, although most are dull

or pallid. In the odd genus Gorgonorhynchus (Gr. Gorgo, name of a

female monster of terrible aspect, + rhynchos, beak, snout) the proboscis is

divided into many proboscides, which

appear as a mass of wormlike structures

when everted.

With a few exceptions, the general body plan of the nemerteans is similar to that of turbellarians. Like the latter, their epidermis is ciliated and has many gland cells. Another striking similarity is the presence of flame cells in the excretory system. Rhabdites have been found in several nemerteans, including Lineus. However, nemerteans differ from flatworms in their reproductive system. They are mostly dioecious. In marine forms there is a ciliated pilidium larva (Gr. pilidion, a small felt nightcap) (Figure 14-26). This helmet-shaped larva has a ventral mouth but no anus— another flatworm characteristic. It also has some resemblance to trochophore larvae that are found in annelids and molluscs. Other flatworm characteristics are the presence of bilateral symmetry and a mesoderm and lack of a coelom. Present evidence indicates that the nemerteans came from an ancestral form similar in body plan to Platyhelminthes.

Nemerteans show some derived features absent from flatworms. One of these is the eversible proboscis and its sheath, for which there are no counterparts among Platyhelminthes. Another difference is the presence of an anus in adults, producing a complete digestive system. A digestive system with an anus is more efficient because ejection of waste materials back through the mouth is not necessary. Nemerteans are also the simplest animals to have a blood-vascular system.

A few nemerteans occur in moist soil and fresh water, but by far the larger number are marine. At low tide they are often coiled under stones. It seems probable that they are active at high tide and quiescent at low tide. Some nemerteans such as Cerebratulus (L. cerebrum, brain, + ulus, dim. suffix) often live in empty mollusc shells. The small species live among seaweed, or they may be found swimming near the surface of the water. Nemerteans are often secured by dredging at depths of 5 to 8 m or deeper. A few are commensals or parasites. Prostoma rubrum (Gr. pro, before, in front of, + stoma, month) which is 20 mm or less in length, is a well-known freshwater species.

Form and Function

Nemerteans are slender worms and very fragile (Figure 14-25) with a great diversity in size. Longer ones are difficult to study in the laboratory. Amphiporus (Gr. amphi, both sides of, + porus, pore) (Figure 14-24), which is taken here as a representative type, is one of the smaller ones. It is from 20 to 80 mm long and about 2.5 mm wide. It is dorsoventrally flattened and has rounded ends. The body wall consists of an epidermis of ciliated columnar cells and layers of circular and longitudinal muscles (Figure 14-27A). A partly gelatinous parenchyma fills the space around the visceral organs. Ocelli are located at the anterior end. The thicklipped mouth is anteroventral, with the opening of the proboscis just above it.

The proboscis is not connected with the digestive tract but is an eversible organ that can be protruded from its cavity, the rhynchocoel, and used for defense and catching prey (Figure 14- 24). It lies within a sheath to which it is attached by muscles. The rhynchocoel is filled with fluid, and by muscular pressure on this fluid the anterior part of the tubular proboscis is everted, or turned inside out. The proboscis apparatus is an invagination of the anterior body wall, and its structure therefore duplicates that of the body wall. Retractor muscles attached at the end are used to retract the everted proboscis, much like inverting the tip of a finger of a glove by a string attached inside at its tip. The proboscis is armed with a sharp-pointed stylet. A frontal gland also opens at the anterior end by a pore.

Locomotion

Nemerteans can move with considerable speed by the combined action of their well-developed musculature and cilia. They glide mainly against a substratum; some species use muscular waves in crawling. Some nemerteans have the interesting method of protruding the proboscis, attaching themselves by means of the stylet, and then drawing their body forward to the attached position.

Feeding and Digestion

Nemerteans are carnivorous and voracious, eating either dead or living prey. In seizing prey they thrust out the slime-covered proboscis, which quickly ensnares prey by wrapping around it (Figure 14-24A). The stylet also pierces and holds the prey. Then retracting the proboscis, the nemertean draws the prey near its mouth, where it is engulfed by the esophagus that is thrust out to meet it.

The digestive system is complete and extends straight through the length of the body to the terminal anus, lying ventral to the proboscis sheath. The esophagus is straight and opens into a dilated part of the tract, the stomach. The blind anterior end of the intestine as well as the main intestine is provided with paired lateral ceca. The alimentary tract is lined with cilated epithelium, and in the wall of the esophagus there are glandular cells.

Digestion is largely extracellular in the intestinal tube, and when the food is ready for absorption, it passes through the cellular lining of the intestinal tract into the blood-vascular system. Indigestible material passes out the anus (Figure 14-24B), in contrast to Platyhelminthes in which it leaves by the mouth.

Circulation

The blood-vascular system is simple and enclosed with a single dorsal vessel and two lateral vessels (Figure 14-27B) connected by transverse vessels. All three longitudinal vessels join together anteriorly to form a type of collar. The blood is usually colorless, containing nucleated corpuscles. However, in some nemerteans the blood is red, green, yellow, or orange from the presence of pigments whose function is unknown. There is no heart, and blood is propelled by the muscular walls of the blood vessels and by bodily movements.

Excretion and Respiration

The excretory system contains a pair of lateral tubes with many branches and flame cells (Figure 14-27B). Each lateral tube opens to the outside by one or more pores. Waste is picked up from the parenchymal spaces and blood by flame cells and carried by the excretory ducts to the outside. Many protonephridia are so closely associated with the circulatory system that their function may be truly excretory, in contrast to their apparently osmoregulatory function in Platyhelminthes. Respiration occurs through the body surface.

Nervous System

The nervous system includes a brain composed of four fused ganglia, one pair dorsal and one pair ventral, united by commissures (connecting nerves). Five longitudinal nerves extend from the brain posteriorly—a large lateral trunk on each side of the body, paired dorsolateral trunks, and one middorsal trunk. These are connected by a network of nerve fibers. From the brain, nerves run to the proboscis, to the ocelli and other sense organs, and to the mouth and esophagus. In addition to ocelli, there are other sense organs, such as tactile papillae, sensory pits and grooves, and probably auditory organs.

Reproduction and Development

The reproductive system in Amphiporus is dioecious. The gonads in either sex lie between the intestinal ceca (Figure 14-24). From each gonad a short duct (gonopore) runs to the dorsolateral body surface. Eggs and sperm are discharged into the water, where fertilization occurs. Egg production in females is usually accompanied by degeneration of the other visceral organs.

Nemerteans have a spiral, determinate cleavage (Figures 8-7C and 8-10). The mesoderm is derived partly from the endoderm and partly from the ectoderm. The rhyncocoel develops as a cavity in the mesoderm and is, therefore, technically a coelomic cavity, but it is not homologous to the coelom in other phyla.

A pilidium larva (Figure 14-26) develops, which bears a dorsal spike of fused cilia and a pair of lateral lobes. The entire larva is covered with cilia and has a mouth and alimentary canal but no anus. In some nemerteans the zygote develops directly without undergoing metamorphosis. The freshwater species, Prostoma rubrum, is hermaphroditic. A few nemerteans are viviparous.

Regeneration

Nemerteans have great powers of regeneration. At certain seasons some of them fragment by autotomy, and from each fragment a new individual develops. Autotomy is especially noteworthy in the genus Lineus. A fragment from the anterior region will produce a new individual more quickly than will one from the posterior part. Sometimes the proboscis is shot out with such force that it is broken off the body. In such a case a new proboscis develops within a short time.

Characteristics of Phylum Nemertea

Class Enopla (en´o-pla) (Gr. enoplos, armed). Proboscis usually armed with stylets; mouth opens in front of brain. Examples: Amphiporus, Prostoma.

Class Anopla (an´o-pla) (Gr. anoplos, unarmed). Proboscis lacks stylets; mouth opens below or posterior to brain. Examples: Cerebratulus, Tubulanus, Lineus.

Nemerteans (nem-er´te-ans) (Gr. Nemertes, one of the Nereids, unerring one) are often called ribbon worms. Their name refers to the unerring aim of the proboscis, a long muscular tube (Figures 14-23 and 14-24). The phylum is also called Rhynchocoela (ring´kose ´la) (Gr. rhynchos, beak, + koilos, hollow), which also refers to the proboscis. They are thread-shaped or ribbon-shaped worms; nearly all are marine. Some live in secreted gelatinous tubes. There are about 650 species in the group.

|

|

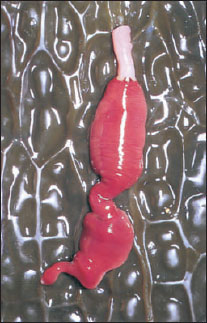

|

| Figure 14-23 Ribbon worm Amphiporus bimaculatus (phylum Nemertea) is 6 to 10 cm long, but other species range up to several meters. The proboscis of this specimen is partially extended at the top; the head is marked by two brown spots. |

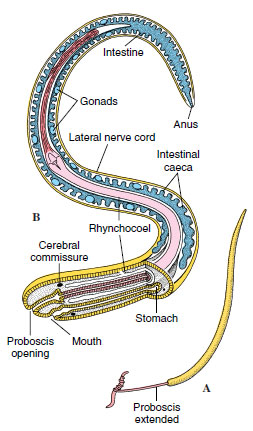

Figure 14-24 A, Amphiporus, with proboscis extended to catch prey. B, Structure of female nemertean worm Amphiporus (diagrammatic). Dorsal view to show proboscis. |

|

| Figure 14-25 Baseodiscus is a genus of nemerteans whose members typically measure several meters in length. This B. mexicanus from the Galápagos Islands was over 10 m long. |

With a few exceptions, the general body plan of the nemerteans is similar to that of turbellarians. Like the latter, their epidermis is ciliated and has many gland cells. Another striking similarity is the presence of flame cells in the excretory system. Rhabdites have been found in several nemerteans, including Lineus. However, nemerteans differ from flatworms in their reproductive system. They are mostly dioecious. In marine forms there is a ciliated pilidium larva (Gr. pilidion, a small felt nightcap) (Figure 14-26). This helmet-shaped larva has a ventral mouth but no anus— another flatworm characteristic. It also has some resemblance to trochophore larvae that are found in annelids and molluscs. Other flatworm characteristics are the presence of bilateral symmetry and a mesoderm and lack of a coelom. Present evidence indicates that the nemerteans came from an ancestral form similar in body plan to Platyhelminthes.

Nemerteans show some derived features absent from flatworms. One of these is the eversible proboscis and its sheath, for which there are no counterparts among Platyhelminthes. Another difference is the presence of an anus in adults, producing a complete digestive system. A digestive system with an anus is more efficient because ejection of waste materials back through the mouth is not necessary. Nemerteans are also the simplest animals to have a blood-vascular system.

A few nemerteans occur in moist soil and fresh water, but by far the larger number are marine. At low tide they are often coiled under stones. It seems probable that they are active at high tide and quiescent at low tide. Some nemerteans such as Cerebratulus (L. cerebrum, brain, + ulus, dim. suffix) often live in empty mollusc shells. The small species live among seaweed, or they may be found swimming near the surface of the water. Nemerteans are often secured by dredging at depths of 5 to 8 m or deeper. A few are commensals or parasites. Prostoma rubrum (Gr. pro, before, in front of, + stoma, month) which is 20 mm or less in length, is a well-known freshwater species.

|

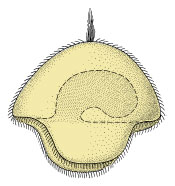

| Figure 14-26 The pilidium larva, typical of most nemerteans, is ciliated and free swimming, and has lateral lobes. |

Form and Function

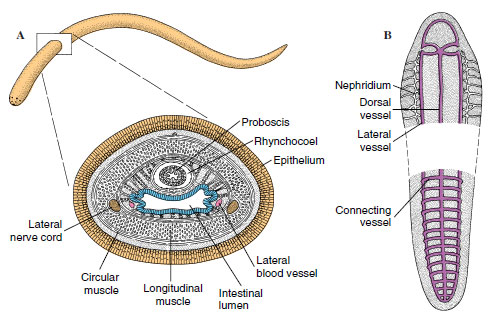

Nemerteans are slender worms and very fragile (Figure 14-25) with a great diversity in size. Longer ones are difficult to study in the laboratory. Amphiporus (Gr. amphi, both sides of, + porus, pore) (Figure 14-24), which is taken here as a representative type, is one of the smaller ones. It is from 20 to 80 mm long and about 2.5 mm wide. It is dorsoventrally flattened and has rounded ends. The body wall consists of an epidermis of ciliated columnar cells and layers of circular and longitudinal muscles (Figure 14-27A). A partly gelatinous parenchyma fills the space around the visceral organs. Ocelli are located at the anterior end. The thicklipped mouth is anteroventral, with the opening of the proboscis just above it.

The proboscis is not connected with the digestive tract but is an eversible organ that can be protruded from its cavity, the rhynchocoel, and used for defense and catching prey (Figure 14- 24). It lies within a sheath to which it is attached by muscles. The rhynchocoel is filled with fluid, and by muscular pressure on this fluid the anterior part of the tubular proboscis is everted, or turned inside out. The proboscis apparatus is an invagination of the anterior body wall, and its structure therefore duplicates that of the body wall. Retractor muscles attached at the end are used to retract the everted proboscis, much like inverting the tip of a finger of a glove by a string attached inside at its tip. The proboscis is armed with a sharp-pointed stylet. A frontal gland also opens at the anterior end by a pore.

Locomotion

Nemerteans can move with considerable speed by the combined action of their well-developed musculature and cilia. They glide mainly against a substratum; some species use muscular waves in crawling. Some nemerteans have the interesting method of protruding the proboscis, attaching themselves by means of the stylet, and then drawing their body forward to the attached position.

Feeding and Digestion

Nemerteans are carnivorous and voracious, eating either dead or living prey. In seizing prey they thrust out the slime-covered proboscis, which quickly ensnares prey by wrapping around it (Figure 14-24A). The stylet also pierces and holds the prey. Then retracting the proboscis, the nemertean draws the prey near its mouth, where it is engulfed by the esophagus that is thrust out to meet it.

The digestive system is complete and extends straight through the length of the body to the terminal anus, lying ventral to the proboscis sheath. The esophagus is straight and opens into a dilated part of the tract, the stomach. The blind anterior end of the intestine as well as the main intestine is provided with paired lateral ceca. The alimentary tract is lined with cilated epithelium, and in the wall of the esophagus there are glandular cells.

Digestion is largely extracellular in the intestinal tube, and when the food is ready for absorption, it passes through the cellular lining of the intestinal tract into the blood-vascular system. Indigestible material passes out the anus (Figure 14-24B), in contrast to Platyhelminthes in which it leaves by the mouth.

Circulation

The blood-vascular system is simple and enclosed with a single dorsal vessel and two lateral vessels (Figure 14-27B) connected by transverse vessels. All three longitudinal vessels join together anteriorly to form a type of collar. The blood is usually colorless, containing nucleated corpuscles. However, in some nemerteans the blood is red, green, yellow, or orange from the presence of pigments whose function is unknown. There is no heart, and blood is propelled by the muscular walls of the blood vessels and by bodily movements.

|

| Figure 14-27 A, Diagrammatic cross section of female nemertean worm. B, Excretory and circulatory systems of nemertean worm. Flame bulbs along nephridial canal are closely associated with lateral blood vessels. |

Excretion and Respiration

The excretory system contains a pair of lateral tubes with many branches and flame cells (Figure 14-27B). Each lateral tube opens to the outside by one or more pores. Waste is picked up from the parenchymal spaces and blood by flame cells and carried by the excretory ducts to the outside. Many protonephridia are so closely associated with the circulatory system that their function may be truly excretory, in contrast to their apparently osmoregulatory function in Platyhelminthes. Respiration occurs through the body surface.

Nervous System

The nervous system includes a brain composed of four fused ganglia, one pair dorsal and one pair ventral, united by commissures (connecting nerves). Five longitudinal nerves extend from the brain posteriorly—a large lateral trunk on each side of the body, paired dorsolateral trunks, and one middorsal trunk. These are connected by a network of nerve fibers. From the brain, nerves run to the proboscis, to the ocelli and other sense organs, and to the mouth and esophagus. In addition to ocelli, there are other sense organs, such as tactile papillae, sensory pits and grooves, and probably auditory organs.

Reproduction and Development

The reproductive system in Amphiporus is dioecious. The gonads in either sex lie between the intestinal ceca (Figure 14-24). From each gonad a short duct (gonopore) runs to the dorsolateral body surface. Eggs and sperm are discharged into the water, where fertilization occurs. Egg production in females is usually accompanied by degeneration of the other visceral organs.

Nemerteans have a spiral, determinate cleavage (Figures 8-7C and 8-10). The mesoderm is derived partly from the endoderm and partly from the ectoderm. The rhyncocoel develops as a cavity in the mesoderm and is, therefore, technically a coelomic cavity, but it is not homologous to the coelom in other phyla.

A pilidium larva (Figure 14-26) develops, which bears a dorsal spike of fused cilia and a pair of lateral lobes. The entire larva is covered with cilia and has a mouth and alimentary canal but no anus. In some nemerteans the zygote develops directly without undergoing metamorphosis. The freshwater species, Prostoma rubrum, is hermaphroditic. A few nemerteans are viviparous.

Regeneration

Nemerteans have great powers of regeneration. At certain seasons some of them fragment by autotomy, and from each fragment a new individual develops. Autotomy is especially noteworthy in the genus Lineus. A fragment from the anterior region will produce a new individual more quickly than will one from the posterior part. Sometimes the proboscis is shot out with such force that it is broken off the body. In such a case a new proboscis develops within a short time.

Characteristics of Phylum Nemertea

- Bilateral symmetry; highly contractile body that is cylindrical anteriorly and flattened posteriorly

- Three germ layers

- Epidermis with cilia and gland cells; rhabdites in some

- Body spaces with parenchyma, which is partly gelatinous

- An eversible proboscis, which lies free in a cavity (rhynchocoel) above the alimentary canal

- Complete digestive system (mouth to anus)

- Body-wall musculature of outer circular and inner longitudinal layers with diagonal fibers between the two; sometimes another circular layer inside the longitudinal layer

- Blood-vascular system with two or three longitudinal trunks

- Acoelomate, although the rhynchocoel technically may be considered a true coelom

- Nervous system usually a four-lobed brain connected to paired longitudinal nerve trunks or, in some, middorsal and midventral trunks

- Excretory system of two coiled canals, which are branched with flame cells

- Sexes separate with simple gonads; asexual reproduction by fragementation; few hermaphrodites; pilidium larvae in some

- No respiratory system

- Sensory ciliated pits or head slits on each side of head, which communicate between the outside and the brain; tactile organs and ocelli (in some)

- In contrast to Platyhelminthes, there are few parasitic nemerteans

Class Enopla (en´o-pla) (Gr. enoplos, armed). Proboscis usually armed with stylets; mouth opens in front of brain. Examples: Amphiporus, Prostoma.

Class Anopla (an´o-pla) (Gr. anoplos, unarmed). Proboscis lacks stylets; mouth opens below or posterior to brain. Examples: Cerebratulus, Tubulanus, Lineus.