Inbreeding depression

AA = p2 + pqF,

Aa = 2pq-2pqF, and aa = q2 + pqF,

It is evident from the above ratio, that if q is large (p will be small) and F is small, the inbreeding increment pF will be relatively small and the increase in frequency of recessive homozygotes will hardly be noticeable. However, if q is very small and p is large, pF provides a notable increase in recessives even when F is fairly small.

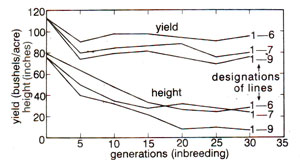

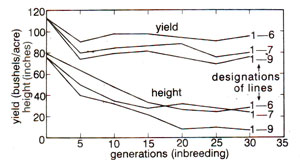

Fig. 47.1. A comparison of three lines of maize, derived from a variety, self-fertilized for 30 generations. Height of stalk is measured in inches and yield of grain in bushels per acre, both plotted on the same scale. Initially, there were four lines, but it became impossible to maintain one of them beyond twenty generations of inbreeding (After Jones, Genetics 24 : 462, 1939).

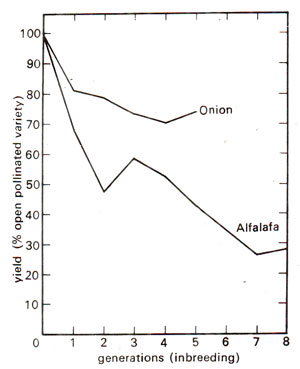

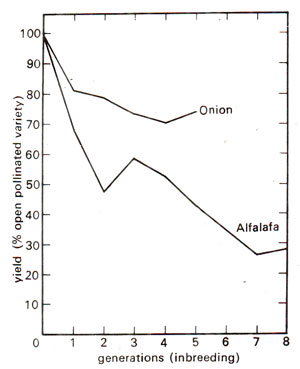

Fig. 47.2. Yields of self-fertilized lines of alfalfa and onions as per cent yield of open pollinated parental varieties. The curve for alfalfa is obviously biased because the later generations are represented by only a few exceptional lines surviving beyond 3 generations of inbreeding, elimination being less severe in onions. (Based on data of Tysdal et al,, 1942, and Jones and Davis, 1942).

Despite this conspicuous decline, maize was found more tolerant to inbreeding than some organisms where few stains survive two or three generations of inbreeding. Alfalfa and onions are such examples. Figure 47.2 illustrates the deterioration in yield of self-fertilised lines of alfalfa and of cross pollinated onions. Upon selfing, in alfalfa, many sub-vital and lethal types appear and the rate of deterioration in general vigour and productivity is appalling. The very small number of lines which manage to survive give a greatly reduced forage yield. But onions (a normally cross pollinated species) are quite tolerant to inbreeding. By comparing Figures 47.1 and 47.2 and taking into account the bias caused by the differences in mortality of inbred lines, one can see that onions are much less depressed in vigour by inbreeding than alfalfa and maize. Among cultivated plants, carrot is another species that deteriorates drastically upon inbreeding.

Fig. 47.1. A comparison of three lines of maize, derived from a variety, self-fertilized for 30 generations. Height of stalk is measured in inches and yield of grain in bushels per acre, both plotted on the same scale. Initially, there were four lines, but it became impossible to maintain one of them beyond twenty generations of inbreeding (After Jones, Genetics 24 : 462, 1939).

Fig. 47.2. Yields of self-fertilized lines of alfalfa and onions as per cent yield of open pollinated parental varieties. The curve for alfalfa is obviously biased because the later generations are represented by only a few exceptional lines surviving beyond 3 generations of inbreeding, elimination being less severe in onions. (Based on data of Tysdal et al,, 1942, and Jones and Davis, 1942).

Among the cross pollinated species, fairly tolerant to inbreeding, are also sunflowers, rye, timothy, smooth broomgrass and orchardgrass. The number of recessive abnormals appearing on inbreeding seems to be less in these species than in maize. There are also species in which inbreeding can be continued indefinitely with seeming impunity. The self-pollinating species are the best example of this category but some of the normally cross fertilizing species of plants, like cucurbits, also fall in this category.