Trisomy

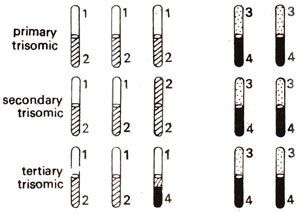

Fig. 20.2. Three kinds of trisomics.

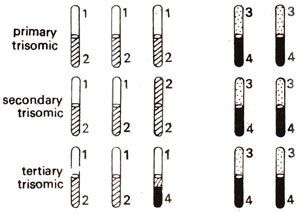

Fig. 20.3. Trisomic conditions associated with changes in fruit morphology in Datura stramonium.

Fig. 20.2. Three kinds of trisomics.

Fig. 20.3. Trisomic conditions associated with changes in fruit morphology in Datura stramonium.

One of the most extensively studied trisomic series is that produced and studied by T. Tsuchiya (who died in May, 1992) in barley. Trisomics are also known in Homo sapiens (human beings). Trisomy for certain chromosomes causes definite morphological abnormalities in human beings.

Mongolism (Down's syndrome) is one such feature, which is common in children and is characterized by mental retardation, a short body, swollen tongue and eyelid folds resembling those of Mongolian races (for details, see Human Genetics). Other cases of trisomy are also known in a number of different plant and animal species.

Cytology of trisomics.

A trisomic has an extra chromosome which is homologous to one of the chromosomes of the complement. Therefore, it forms a trivalent. This trivalent may take a variety of shapes in primary and secondary trisomics as shown in Figure 20.5. In a tertiary trisomic a characteristic pentavalent is observed.

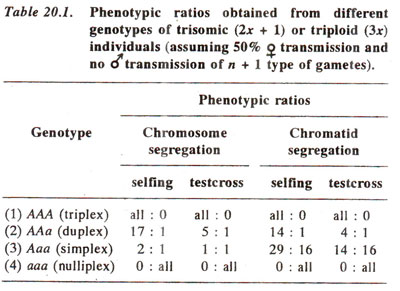

Trisomics are also used for locating genes on specific chromosomes. If a particular gene is located on the chromosome involved in trisomy, segregation in the progeny of this trisomic will not follow a Mendelian pattern, but the ratio will deviate from normal 3 : 1 F2 and 1 : 1 test cross ratios. The expected ratios in trisomics can be worked out, and are given in Table 20.1. In Table 20.1, ratios based on chromosome segregation as well as those based on chromatid segregation are given. Chromosome segregation will hold good, when the gene is located very close to centromere permitting no crossing over between the gene and the centromere, so that both sister chromatids will be similar. In chromatid segregation, gene is located away from centromere permitting crossing over between gene and centromere.