Biological control

Content

Benefits: Non-toxic, no build-up of resistant pests and diseases. Limitations: Needs careful introduction and knowledge of life cycles. Can easily be affected by pesticides. There are two sources of ‘natural enemies’ to pests, the local species and the exotic ones. Many pests of outdoor horticultural crops such as peach-potato aphid are indigenous (i.e. they are present in wild plant communities in the UK). Such pests are often reduced in nature by other organisms which, as predators, eat the pest, or, as parasites, lay eggs within the pest. These beneficial organisms, found also on horticultural crops, are to be encouraged and in some cases are deliberately introduced. A range of important organisms useful in horticulture is now described in some detail. Indigenous predators and parasites Wild birds It has been shown that a pair of blue tits can consume 10 000 caterpillars and one million aphids in a 12 month period. The installation of tit boxes is a worthwhile activity. Wrens, thrushes and blackbirds similarly contribute to the control of garden insects. Hedgehogs Hedgehogs belong to the insectivore group of mammals, but are omnivorous. Although their preferred diet is insects (up to 200 g per day) they will eat slugs. Care must be taken that they are not exposed to dead slugs which have consumed slug bait containing methiocarb or methaldehyde, as these would be toxic to the hedgehog. Hedgehogs are encouraged to enter gardens by means of small holes cut into the base of a fence panel. Within gardens, heaps of logs and piles of leaf litter in a quiet location are suitable for their daytime and overwintering retreat. Wooden hedgehog shelters are commercially available. The black-kneed capsid The black-kneed capsid (Blapharidopterus angulatus) is an insect found on fruit trees alongside its pestilent relative, the common green capsid. It eats more than 1000 fruit tree red spider mites per year. Its eggs are laid in August and survive the winter. Winter washes used by professional horticulturalists against apple pests and diseases often kill off this useful insect. The closely related anthocorid bugs, such as Anthocoris nemorum, are predators on a wide range of pests, such as aphids, thrips, caterpillars and mites, and have recently been used for biological control in greenhouses. Lacewings Lacewings, such as Chrysopa carnea, lay several hundred eggs per year on the end of fine stalks, located on leaves. Several are useful horticultural predators, their hairy larvae eating aphids and mite pests, often reaching the prey in leaf folds where ladybirds cannot reach. Ladybird beetle The 40 species of ladybird beetle are a welcome sight to the professional horticulturist and lay person alike. Almost all are predatory. The red two-spot ladybird (Adalia bipunctata) emerges from the soil in spring, mates and lays about 1000 elongated yellow eggs on the leaves of a range of weeds, such as nettles, and crops such as beans, throughout the growing season. Both the emerging slate-grey and yellow larvae and the adults feed on a range of aphid species. Wooden ladybird shelters and towers are now available to encourage the overwintering of these useful predators. A worrying development in the last few years has been the rapid spread and increase of the harlequin ladybird from South-East Asia. This species is larger (6–8 mm long) and rounder than the two-spot species (4–5 mm). It has a wider food range than other ladybird species, consuming other ladybird’s eggs and larvae, and eggs and caterpillars of moths. Furthermore, it is able to bite humans and be a nuisance in houses when it comes out of hibernation. Carabid beetles The ground beetle (such as Bembidion lampros), a 2 cm long black species (see Figure 16.5), is one of many active carabid beetles that actively predates on soil pests such as root fly eggs, greatly reducing their numbers.

Hoverflies Superficially resembling wasps, these are commonly seen darting or hovering above flowers in summer. Several of the 250 British species, such as Syrphus ribesii, lay eggs in the midst of aphid colonies, and the legless light-green coloured grubs consume large numbers of aphids. The flowers of some garden plants are especially useful in providing pollen for the adults and therefore encouraging aphid control in the garden. Summer flowering examples are poached-egg plant (Limnanthes douglasii), baby-blue-eyes (Nemophila menziesii) and Californian poppy (Romneya coulteri). Later summer and autumn examples are Phacelia tanacetifolium and ice plant (Sedum spectabile). Mites and spiders Predatory mites such as Typhlodromus pyri eat fruit tree red spider mite and contribute importantly to its control. The numerous species of webforming and hunting spiders help in a very important but unspecific way in the reduction of all forms of insects.

The much maligned common wasp (Vespula vulgaris) is a voracious spring and summer predator on caterpillars, which are fed in a paralyzed state to the developing wasp grubs. Digger wasps also help control caterpillar numbers and benefit from dead hollow stems of garden plant which they use as nests all year round. There are about 3000 parasitic wasp species of the families Ichneumonidae, Braconidae and Chalcidae found on other insects in Britain. Ichneumons (Opion spp. see Figure 16.5) lay eggs in many moth caterpillars. The braconid wasp (Apanteles glomeratus) lays about 150 eggs inside a cabbage white caterpillar and the parasites pupate outside the pest’s dead body as yellow cocoon masses. The chalcid (Aphelinus mali) parasitizes woolly aphid on apples.

The spiracles of insects provide access to specialized parasitic fungi, particularly under damp conditions. In some years, aphid numbers are quickly reduced by the infection of the fungus Entomophthora aphidis, while codling moth caterpillars on apple may be enveloped by Beauveria bassiana. Cabbage white caterpillar populations are occasionally much reduced by a virus, which causes them to burst.

Increased attention is being given by horticulturalists to the careful selection of pesticides (if they are needed) to avoid unnecessary destruction of indigenous predator and parasite numbers.

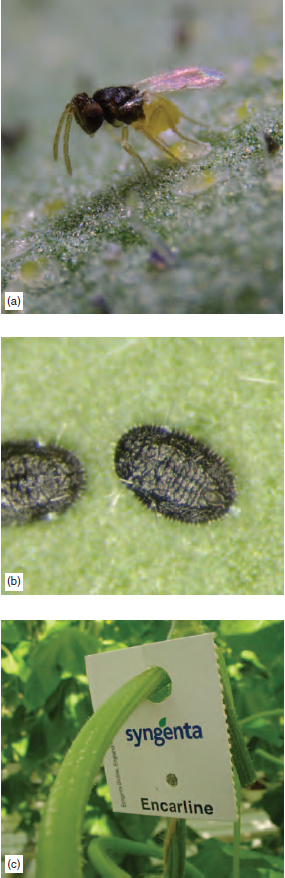

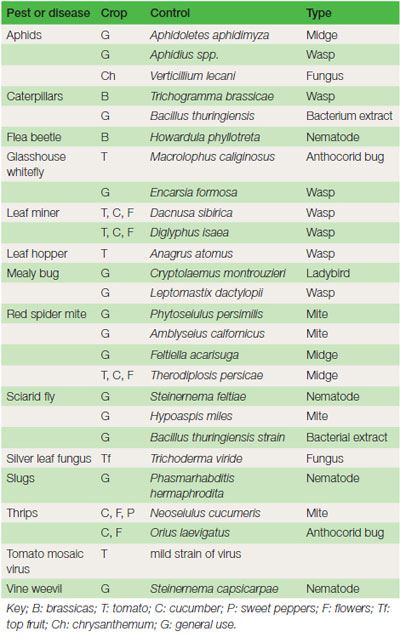

Exotic predators and parasites In greenhouses and polythene tunnels, high temperatures often all year round and sub-tropical species of plants bring with them exotic pests and diseases. Further, the increase of both pests and diseases is much quicker than comparable pests or diseases growing outdoors. Also, these greenhouse inhabiting organisms have, over the last half-century, developed resistance to almost all available pesticides. Biological control of exotic pests requires exotic predators and parasites. And so the health of the major greenhouse crops is in large measure due to two organisms: a South American mite which eats all stages of the glasshouse red spider mite, and a tiny South-East Asian wasp that parasitizes the glasshouse whitefly. The conditions in a greenhouse have two advantages for biological control. Firstly, the environment is relatively isolated so that the controlling organisms are not likely to disappear. Secondly, the glasshouse environment is relatively stable and allows biological control to be more measured (than in the outdoor situation) with interactions between pests and their predator or parasite being more predictable. Almost all commercial production of glasshouse crops in the UK now uses biological control. The two commonest biological control organisms are described below in some detail. Much more information is available from commercial companies or from the Internet. A more extensive listing of commercially available biological control species is given in Table 16.1 . Phytoseiulus persimilis (see Figure 16.7) This is a 1 mm globular, deep orange, predatory tropical mite used in greenhouse production to control glasshouse red spider mite. It is raised on spider mite-infected beans and then evenly distributed throughout the crop, such as cucumbers, at the rate of about one predator per plant. Some growers who have suffered repeatedly from the pest first introduce the red spider mite throughout the crop at the rate of about five mites per plant a week before predator application, thus maintaining even levels of pest–predator interaction. The predator’s short egg–adult development period (7 days), laying potential (50 eggs per life cycle) and appetite (five pest adults eaten per day), explain its extremely efficient action. Encarsia formosa (see Figure 16.8) This is a small (2 mm) wasp which lays an egg into the glasshouse whitefly scale, causing it to turn black and eventually to release another wasp. This parasite is raised commercially on whitefly-infested tobacco plants. It is introduced to the crop, such as tomato, at a rate of about 100 blackened scales per 100 plants. The parasite’s introduction to the crop is most successful when the whitefly levels are low (recommended less than one whitefly per 10 plants). Its mobility (about 5 m) and successful parasitism are most effective at temperatures greater than 22°C when its egg-laying ability exceeds that of the whitefly. The wasp lays most of its 60 or more eggs within a few days of emergence from the black scale. Thus, a series of weekly applications from late February onwards ensures that viable eggs are laid whenever the susceptible whitefly scale stage is present. The appearance of newly infected black scales on leaves is often taken as an indication that parasite introductions can be stopped. An understanding of each pest’s and each biological control organism’s life cycle is vital to ensure success in control. A combination of biological methods may be used on some crops, such as chrysanthemums, tomatoes, peppers, aubergines and cucumbers in order to simultaneously control a range of organisms occurring on the crop at the same time (see Table 16.1, and integrated control). Several specialist firms now have contracts to apply biological control organisms to greenhouse units. There are several practical points that confront growers in both the outdoor and the glasshouse situation. Safe practice The main problems with biological control are:

|