The Ophidia

This order of Reptiles has been divided as follows:- The palatine bones widely separated, and their long axes longitudinal; a transverse bone; the pterygoids united with the quadrate bones.

- None of the maxillary teeth grooved or canalieulated.

- Some of the posterior maxillary teeth grooved.

- Grooved anterior maxillary teeth succeeded by solid teeth.

- Maxillary teeth few, canaliculated, and fanglike.

- The palatine bones meet, or nearly meet, in the base of the skull, and

their long axes are transverse; no transverse bone; the pterygoids

are not connected with the quadrate bone.

1. Aglyphodontia.

2. Opisthoglyphia.

3. Proteroglyphia,

4. Solenoglyphia.

5. Typhlopidae.

All the Snakes possess a scaly epidermic investment, which it. usually shed in one piece, and reproduced at definite intervals. As a general rule these scales are flat, and overlap one another; but sometimes, as in Acrochordus, they become more tubercle-like, and do not overlap. In the Rattlesnakes (Crotalus) the body is terminated by several loosely-conjoined rings of horny matter, which consist of the modified epidermis of the end of the tail.

The derm does not become ossified in the Ophidia.

|

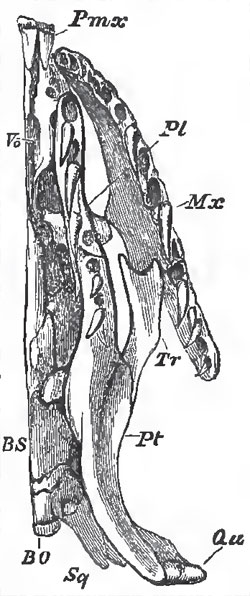

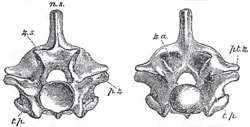

| Fig. 71. - Anterior and posterior views of the dorsal vertebra of a Python: z. s, zygosphene

z. a., zygantrum; p. z., prezzgapophysea; pt. z., postgygapophyses; t, p., transverse processes. |

The transverse processes are short and tubercle-like, and the heads of the ribs which articulate with them are simple. Each rib usually gives off a short upward process at a little distance from its head; it is curved, usually hollow, and terminates, inferiorly, in a cartilage which is always free, no trace of a sternum existing. Strong descending processes are given off from the undersides of many of the presacral vertebrae. In the caudal region, elongated transverse processes take the place of the ribs. Chevron-bones, like those of the Lacertilia, do not exist, but the caudal vertebrae possess bifurcated descending processes, which bear similar relations to the caudal vessels.

The skull differs from the ordinary Lacertilian cranium in the following points:

- That vertical elevation and lateral compression of the

presphenoidal region, which give rise to the interorbital septum,

are wanting; the floor of the cranium being nearly flat,

and the vertical height of its cavity diminishing gradually in

front, so that it remains spacious between the eyes, and in the

frontal region generally. The periotic region is not produced

into parotic processes.

- The boundary-walls of the front half of the cranial cavity are as well ossified as those of its posterior moiety, and the bones which constitute the brain-case are firmly united together.

- On the other hand, the nasal segment is less completely ossified, and may be movable. The premaxillae are usually represented by a single small bone, which very rarely bears teeth. It is connected with the maxillae only by fibrous tissue.

- The palatine bones never unite directly with the vomer, or with the base of the skull, but they are usually connected with the maxillae by transverse bones; and, by the pterygoids, with the mobile quadrate bones. Hence the connection of the palato-maxillary apparatus with the other bones of the skull ia always less close in Ophidia than in Lacertilia, and sometimes it is exceedingly lax.

- The two rami of the mandible are united at the symphysis only by ligamentous fibres, which are often extremely elastic.

- The hyoidean apparatus is very rudimentary, consisting only of a pair of cartilaginous filaments, which are united together in front, and lie parallel with one another beneath the trachea. They have no connection with the skull.

|

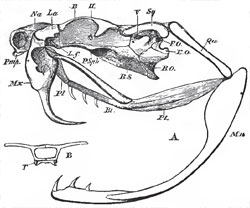

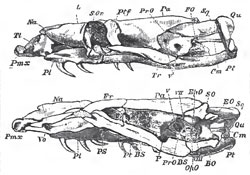

| Fig. 72. - The skull of a Python, viewed from the left side, and in longitudinal section; Cm stapes; Tl, turbinal bone. |

The Ophidia usually possess well-developed post-frontals, and they have large membrane-bones in front of the orbit, which lie upon the cartilaginous nasal chambers, and are ordinarily regarded as lachrymals. Large nasals lie upon the upper surface of the nasal capsule between the lachrymals; and, forming the floor of the front part of the nasal chamber, on each side, is a large concavo-convex bone (Tl, Fig. 72), which extends from the ethmoidal septum to the maxilla, protects the nasal gland, and is commonly termed a turbinal, though, if it be a membrane-bone, it does not truly correspond with the turbinals of the higher Vertebrata. The squamosals are usually well developed. There is no jugal, or quadrato jugal.

Though the general conformation of the skull in the Opihidia is that which has now been described, it presents remarkable modifications in different members of the order, especially in the form and disposition of the bones of the jaws. In the great majority of the Ophidia, the elongated palatine bones have their long axes longitudinal, lie on the outer sides of the internal nasal apertures, and do not enter into the formation of the posterior boundaries of those apertures. Each is connected by a transverse bone with the maxilla, which lies at the side of the oral cavity; and the pterygoids diverge posteriorly toward the quadrate bones, with which they are connected by ligaments.

But, in the remarkable group of the Typhlopidae, the slender palatine bones meet upon the base of the skull in the middle line, and are directed transversely, in such a manner as to bound the posterior nasal apertures behind, as in the Satrachia. There is no transverse bone. The pterygoids lie parallel with one another under the base of the skull, and are not connected with the quadrate bones. The maxillae are short plates of bone which are connected with the outer extremities of the palatine bones, and are directed obliquely toward the middle line of the oral cavity, into which their free edges, armed with teeth, depend.

Again, the first-mentioned, or typical, form of Ophidian skull exhibits two extreme modifications, between which lie all intermediate gradations. At the one end of the scale are the non-venomous Snakes, and especially Python and Tortrix (which belong to the division Aglyphodontia); at the other the poisonous Snakes, and especially Crotalus (Solenoglyphia).

Thus, Python (Figs. 73 and 73) has well-marked premaxillae, large maxillary bones, palatine bones which are firmly united with the pterygoids, and transverse bones which bind the maxillaries and palato-pterygoid bars into one solid framework.

The maxillaries give attachment to a long series of recurved teeth, which are not very unequal in size. And Python (like Tortrix, but unlike all other Ophidia) possesses teeth in the premaxillae.

The squamosal bones are very long, and adhere to the skull, upon which they are slightly movable, only by their anterior ends; and the quadrate bones are borne upon the posterior ends of the squamosals, and are thus, as it were, thrust away from the walls of the skull, The rami of the mandible are loosely connected by an elastic symphysial ligament. Thus, not only can these rami be widely separated from one another, but the squamosal and quadrate bones constitute a kind of jointed lever, the straightening of which permits of the separation of the mandibles from the base of the skull. And all these arrangements, taken together, allow of that immense distention of the throat which is requisite for the passage of the large and undivided prey of the serpent.

In Tortrix, this mechanism does not exist, the short quadrate bone being directly articulated with the skull, while the squamosal, like the post-frontal, is rudimentary. The maxillary bones are also almost fixed to the skull.

In the Rattlesnakes (Crotalus, Fig. 74), the premaxillae are very small and toothless. The maxillary bone has no longer the form of an elongated bar, but is short, subcylindrical, and hollow; its cavity lodges the fossa formed by the integument in front of the eye, which is so conspicuous in these, and sundry other, poisonous Snakes. The upper and inner part of the maxilla articulates with a pulley-like surface furnished to it by the lachrymal, so that the maxilla plays freely backward and forward upon that bone. The lachrymal, again, has a certain amount of motion upon the frontal. The upper edge of the posterior wall of the maxilla is articulated by a hinge-like joint with the anterior end of the transverse bone, which has the form of an extremely elongated and flattened bar connected posteriorly with the pterygoid.

When the mouth is shut, the axis of the quadrate bone is inclined downward and backward. The pterygoid, thrown as far back as it can go, straightens the pterygo-palatine joint, and causes the axes of the palatine and pterygoid bones to coincide. The transverse, also carried back by the pterygoid, similarly pulls the posterior part of the maxilla, and causes its proper palatine face, to which the great channelled poisonfangs are attached, to look backward. Hence these fangs lie along the roof of the mouth, concealed between folds of the mucous membrane. But, when the animal opens its mouth for the purpose of striking its prey, the digastric muscle, pulling up the angle of the mandible, at the same time thrusts the distal end of the quadrate bone forward. This necessitates the pushing forward of the pterygoid, the result of which is twofold; firstly, the bending of the pterygo-palatine joint; secondly, the partial rotation of the maxillary upon its lachrymal joint, the hinder edge of the maxillary being thrust downward and forward. In virtue of this rotation of the maxillary, through about a quarter of a circle, the dentigerous Tace of the maxilla looks downward, and even a little forward, instead of backward, and the fangs are erected into a vertical position. The snake "strikes:" by the simultaneous contraction of the crotaphite muscle, part of which extends over the poisongland, the poison is injected into the wound through the canal of the fang; and, this being withdrawn, the mouth is shut, all the previous movements are reversed, and the parts return to their first position.

No Ophidian possesses any trace of anterior extremities, but the Typhlopidae, the Pythons, Boas, and Tortrices, have rudiments of a pelvis, and the latter Snakes even possess very short representatives of hind-limbs terminated by claws.

The teeth of the Ophidia are short and conical, and become anchylosed to the bones by which they are supported. They may be developed in the premaxillaries, maxillaries, palatines, pterygoids, and the dentary piece of the mandible, but their presence in the premaxillaries is exceptional. In Uropeltis and some other genera, there are no palatine teeth; and in the egg-eating African snake, Rachiodon, the teeth are small and rudimentary upon all the bones which usually bear them. But the inferior spines of eight or nine of the anterior vertebrae are long, and tipped, at their apices, with a dense enamel-like substance. These project through the dorsal wall of the oesophagus into its cavity, and the eggs, which are swallowed whole, are thus broken in a position in which all their contents must necessarily be saved.

In the majority of the non-venomous Snakes the teeth are simply conical, but in the others, and in all the poisonous Snakes, some of the maxillary teeth (which are usually longer than the rest) become grooved in front. In the Solenoglyphia, or Vipers and Rattlesnakes, the maxillary teeth are reduced to two or three long fangs, the groove in the front of which is converted into a canal open at each end, by the meeting of its edges. The teeth of the Snakes are replaced by others which are developed close to the bases of the old ones.

Ophidia are not known in the fossil state before the older tertiaries.