A Brief Survey of Crustaceans

A Brief Survey of Crustaceans

Crustaceans are an extensive group with many subdivisions. They have many structures, habitats, and modes of living. Some are much larger than crayfishes; others are smaller, even microscopic. Some are highly developed and specialized; others have simpler organization.

Class Remipedia

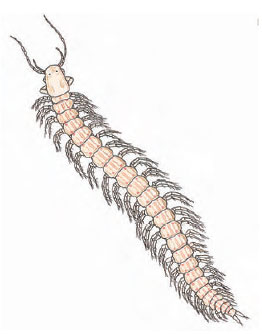

Remipedia (Figure 19-14) is a very small, recently described class of Crustacea. The 10 species described so far have come from caves with connections to the sea. Remipedes have some very primitive features. There are 25 to 38 trunk segments (thorax and abdomen), all bearing paired, biramous, swimming appendages that are all essentially alike. Antennules are biramous. Both pairs of maxillae and a pair of maxillipeds, however, are prehensile and apparently adapted for feeding. The shape of the swimming appendages is similar to that found in Copepoda, but unlike copepods and cephalocarids, swimming legs are directed laterally rather than ventrally.

Class Cephalocarida

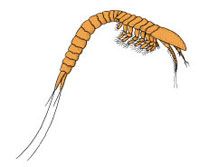

Cephalocarida (Figure 19-15) is also a small group, with only nine species known. Cephalocarids occur along both coasts of the United States, in the West Indies, and in Japan. They are 2 to 3 mm long and have been found in bottom sediments from the intertidal zone to a depth of 300 m. Some of their features are quite primitive. Thoracic limbs are very similar to each other, and second maxillae are similar to thoracic limbs. The second maxillae and the first seven thoracic legs have a large epipod on their protopod, and the protopod is a single joint. Cephalocarids have no eyes, carapace, or abdominal appendages. True hermaphrodites, they are unique among Arthropoda in discharging both eggs and sperm through a common duct.

Class Branchiopoda

Class Branchiopoda

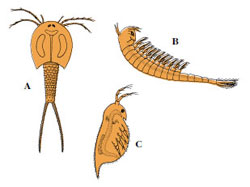

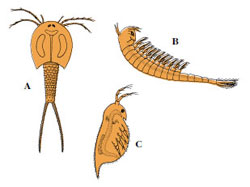

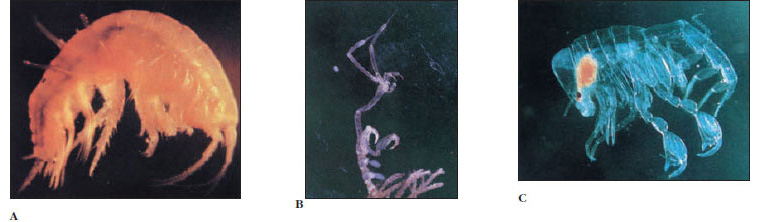

Branchiopoda also represents a crustacean type with some primitive characters. Four orders are recognized: Anostraca (fairy shrimp and brine shrimp, Figure 19-16B), with no carapace; Notostraca (tadpole shrimp, Figure 19-16A), whose carapace forms a large dorsal shield; Conchostraca (clam shrimp), with a bivalve carapace usually enclosing the entire body; and Cladocera (water fleas, Figure 19-16C), typically with a carapace that encloses the body but not the head. Branchiopods have reduced first antennae and second maxillae. Their legs are flattened and leaflike (phyllopodia) and are the chief respiratory organs (hence the name branchiopods). Most branchiopods also use their legs for suspension feeding, and in groups other than the cladocerans, they use their legs for locomotion as well.

Most branchiopods are freshwater forms. The most important and abundant order is Cladocera, which often forms a large segment of freshwater zooplankton. Their reproduction is very interesting and is reminiscent of that occurring in some rotifers (Pseudocoelomate Animals). During summer they often produce only females, by parthenogenesis, rapidly increasing the population.

With the onset of unfavorable conditions, some males are produced, and eggs that must be fertilized are produced by normal meiosis. Fertilized eggs are highly resistant to cold and desiccation, and they are very important for survival of the species over winter and for passive transfer to new habitats. Most cladocerans have direct development, whereas other branchiopods have gradual metamorphosis.

Class Maxillopoda

Class Maxillopoda includes a number of crustacean groups traditionally considered classes themselves. Specialists have recognized evidence that these groups descended from a common ancestor and thus form a monophyletic group within Crustacea. They basically have five cephalic, six thoracic, and usually four abdominal somites plus a telson, but reductions are common. There are no typical appendages on the abdomen. The eye of the nauplius (when present) has a unique structure and is referred to as a maxillopodan eye.

Subclass Ostracoda

Members of Ostracoda are, like conchostracans, enclosed in a bivalve carapace and resemble tiny clams, 0.25 to 8 mm long (Figure 19-17). Ostracods show considerable fusion of trunk somites, and numbers of thoracic appendages are reduced to two or none. Feeding and locomotion are principally by use of the head appendages. Most ostracods live on the bottom or climb on plants, but some are planktonic or burrowing, and a few are parasitic. Feeding habits are diverse; there are particle, plant, and carrion feeders and predators. They are widespread in both marine and freshwater habitats. Development is gradual metamorphosis.

Subclass Mystacocarida Mystacocarida is a class of tiny crustaceans (less than 0.5 mm long) that live in interstitial water between sand grains of marine beaches (psammolittoral habitat) (Figure 19-18). Only 10 species have been described, but mystacocarids are widely distributed through many parts of the world.

Subclass Mystacocarida Mystacocarida is a class of tiny crustaceans (less than 0.5 mm long) that live in interstitial water between sand grains of marine beaches (psammolittoral habitat) (Figure 19-18). Only 10 species have been described, but mystacocarids are widely distributed through many parts of the world.

Subclass Copepoda

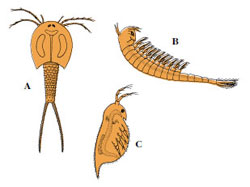

This group is second only to Malacostraca in numbers of species. Copepods are small (usually a few millimeters or less in length) and rather elongate, tapering toward the posterior. They lack a carapace and retain the simple, median, nauplius (maxillopodan) eye in adults (Figure 19-19). They have a single pair of uniramous maxillipeds and four pairs of rather flattened, biramous, thoracic swimming appendages. The fifth pair of legs is reduced. The posterior part of the body is usually separated from the anterior, appendage-bearing portion by a major articulation. Antennules are often longer than other appendages. Copepoda have become very diverse and evolutionarily enterprising, with large numbers of symbiotic as well as freeliving species. Many parasites are highly modified, and adults may be so highly modified (and may depart so far from the description just given) that they can hardly be recognized as arthropods, let alone crustaceans.

Ecologically, free-living copepods are of extreme importance, often dominating the primary consumer level in aquatic communities. In many marine localities the copepod Calanus is the most abundant organism in the zooplankton and has the greatest proportion of the total biomass. In other localities it may be surpassed in the biomass only by euphausids. Calanus forms a major portion of the diet of such economically and ecologically important fish as herring, menhaden, sardines, and larvae of larger fish and (along with euphausids) is an important food item for some whales and sharks. Other genera commonly occur in marine zooplankton, and some forms such as Cyclops and Diaptomus may form an important segment of freshwater plankton. Many species of copepods are parasites of a wide variety of other marine invertebrates and marine and freshwater fish, and some of the latter are of economic importance. Some species of free-living copepods serve as intermediate hosts of parasites of humans, such as Diphyllobothrium (a tapeworm) and Dracunculus (a nematode), and of other animals.

Development in copepods is indirect, and some highly modified parasites show striking metamorphoses.

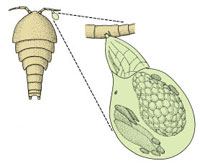

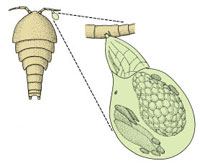

Subclass Tantulocarida

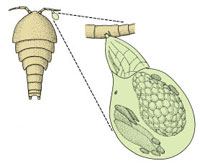

Tantulocarida (Figure 19-20) is the most recently described class (here considered a subclass) of crustaceans (1983). Only about 12 species are known so far. They are tiny (0.15 to 0.2 mm) copepod-like ectoparasites of other deep-sea benthic crustaceans. They have no recognizable head appendages except one pair of antennae on sexual females. The life cycle is not known with certainty, but present evidence suggests that there is a parthenogenetic cycle and a bisexual cycle with fertilization. Tantulus larvae penetrate the cuticle of their hosts by a mouth tube. Then their abdomen and all thoracic limbs are lost during metamorphosis to the adult. Alone among maxillopodans, juveniles bear six to seven abdominal somites, but other evidence supports inclusion in this class.

Tantulocarida (Figure 19-20) is the most recently described class (here considered a subclass) of crustaceans (1983). Only about 12 species are known so far. They are tiny (0.15 to 0.2 mm) copepod-like ectoparasites of other deep-sea benthic crustaceans. They have no recognizable head appendages except one pair of antennae on sexual females. The life cycle is not known with certainty, but present evidence suggests that there is a parthenogenetic cycle and a bisexual cycle with fertilization. Tantulus larvae penetrate the cuticle of their hosts by a mouth tube. Then their abdomen and all thoracic limbs are lost during metamorphosis to the adult. Alone among maxillopodans, juveniles bear six to seven abdominal somites, but other evidence supports inclusion in this class.

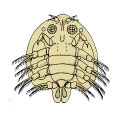

Subclass Branchiura

Branchiurans are a small group of primarily fish parasites, which, despite their name, have no gills (Figure 19-21). Members of this group are usually between 5 and 10 mm long and may be found on marine or freshwater fish. They typically have a broad, shieldlike carapace, compound eyes, four biramous thoracic appendages for swimming, and a short, unsegmented abdomen. Second maxillae have become modified as suction cups, enabling the parasites to move about on their fish host or even from fish to fish. Development is almost direct: there is no nauplius, and young resemble adults except in size and degree of development of appendages.

Subclass Cirripedia

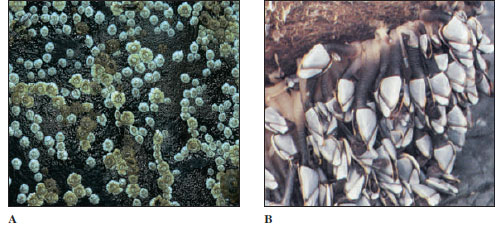

Cirripedia includes barnacles (order Thoracica), which are usually enclosed in a shell of calcareous plates, as well as three smaller orders of burrowing or parasitic forms. Barnacles are sessile as adults and may be attached to the substrate by a stalk (gooseneck barnacles) (Figure 19-22B) or directly (acorn barnacles) (Figure 19-22A). Typically the carapace (mantle) surrounds the body and secretes a shell of calcareous plates. The head is reduced, the abdomen is absent, and the thoracic legs are long, many-jointed cirri with hairlike setae. The cirri are extended through an opening between the calcareous plates to filter from the water the small particles on which the animal feeds (Figure 19-22). Although all barnacles are marine, they are often found in the intertidal zone and are therefore exposed to drying and sometimes fresh water for some periods of time. During these periods the aperture between the plates closes to a very narrow slit.

Barnacles are hermaphroditic and undergo a striking metamorphosis during development. Most hatch as nauplii, which soon become cyprid larvae, so called because of their resemblance to an ostracod genus Cypris. They have a bivalve carapace and compound eyes. Cyprids attach to the substrate by means of their first antennae, which have adhesive glands, and begin their metamorphosis. This involves several dramatic changes, including secretion of the calcareous plates, loss of eyes, and transformation of the swimming appendages to cirri.

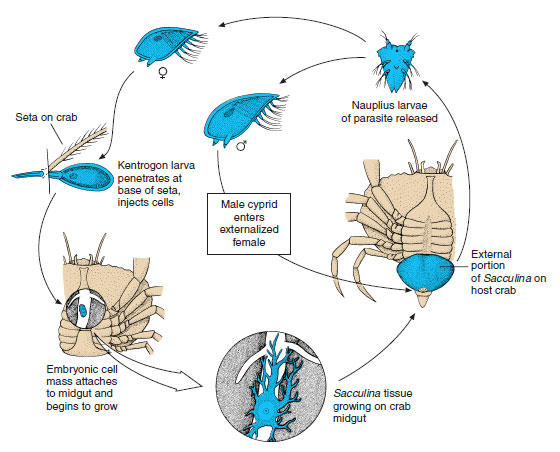

Members of order Rhizocephala, such as Sacculina, are highly modified parasites of crabs. They start life as cyprid larvae, just as other cirripedes, but when they find a host, most species metamorphose into a kentrogon (Gr. kentron, a point, spine, + gonos, progeny) which injects cells of the parasite into the hemocoel of the crab (Figure 19-23). Eventually, rootlike absorptive processes grow throughout the crab’s body, and the parasite’s reproductive structures become externalized between the cephalothorax and the reflexed abdomen of the crab.

Class Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the largest class of Crustacea and shows great diversity. The diversity is indicated by the higher classification of the group, which includes three subclasses, 14 orders, and many suborders, infraorders, and superfamilies. We confine our coverage to mentioning a few of the most important orders.

Order Isopoda

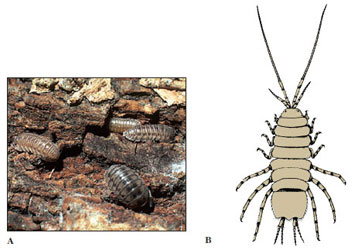

Isopods are one of the few crustacean groups to have successfully invaded terrestrial habitats in addition to freshwater and seawater habitats and the only crustaceans to have become truly terrestrial.

They are commonly dorsoventrally flattened, lack a carapace, and have sessile compound eyes; maxillipeds are their first pair of thoracic limbs. The remaining thoracic limbs lack exopods and are similar, while the abdominal appendages bear the gills and, except the uropods, also are similar to each other (hence the name isopods).

Common land forms are the sow bugs, or pill bugs (Porcellio and Armadillidium, Figure 19-24A), which live under stones and in damp places. Although they are terrestrial, they do lack an efficient cuticular covering and other adaptations possessed by insects to conserve water; therefore they must live in moist conditions. Caecidotea (Figure 19-24B) is a common freshwater form found under rocks and among aquatic plants. Ligia is a common marine form that scurries about on the beach or rocky shore. Some isopods are parasites of fish (Figure 19-25) or crustaceans and some are highly modified. Development is essentially direct but may be highly metamorphic in specialized parasites.

Order Amphipoda

Amphipods resemble isopods in that the members lack a carapace and have sessile compound eyes and one pair of maxillipeds (Figure 19-26). However, they are usually compressed laterally, and their gills are in the typical thoracic position. Furthermore, their thoracic and abdominal limbs are each arranged in two or more groups that differ in form and function. For example, one group of abdominal legs may be for swimming and another for jumping. There are many marine amphipods, including some beachdwelling forms (for example, Orchestia, a beach hopper), numerous freshwater genera (Hyalella and Gammarus), and a few parasites. Development is direct.

Order Euphausiacea

Euphausiacea is a group of only about 90 species, but they are important as the oceanic plankton known as “krill” (Figure 19-27). They are about 3 to 6 cm long, have a carapace that is fused with all thoracic segments but does not entirely enclose the gills, have no maxillipeds, and have all thoracic limbs with exopods. Most are bioluminescent, with a light-producing substance in an organ called a photophore. Some species may occur in enormous swarms, covering up to 45 m2 and extending up to 500 m in one direction. They form a major portion of the diet of baleen whales and many fishes. Eggs hatch as nauplii, and development is indirect.

Order Decapoda

Order Decapoda

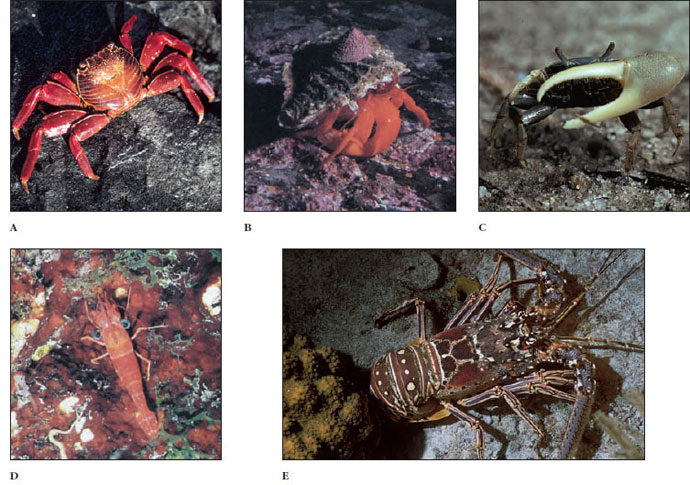

Decapods have three pairs of maxillipeds and five pairs of walking legs, of which the first is modified in many to form pincers (chelae). They range in size from a few millimeters to the largest of all arthropods, Japanese spider crabs, whose chelae span 4 m. Crayfishes, lobsters, crabs, and “true” shrimp belong in this group (Figures 19-28 and 19-29). There are about 10,000 species of decapods, and the order is extremely diverse. They are very important ecologically and economically, and numerous species are relished as items of food for humans.

Crabs, especially, exist in a great variety of forms. Although resembling crayfishes, they differ from the latter in having a broader cephalothorax and reduced abdomen. Familiar examples along the seashore are hermit crabs (Figure 19-28B), which live in snail shells because their abdomens are not protected by the same heavy exoskeleton as are the anterior parts, fiddler crabs, Uca (Figure 19-28C), which burrow in sand just below the high-tide level and come out to run about over the sand while the tide is out; and spider crabs such as Libinia and interesting decorator crabs Oregonia and others, which cover their carapaces with sponges and sea anemones for protective camouflage (Figure 19-29).

Classification of Subphylum Crustacea

Higher classification of Crustacea is complex and subject to change as new data become available. The following relies on several sources. We are omitting many smaller taxa.

Class Remipedia

(ri-mi-pee´dee-a) (L. remipedes, oar-footed). No carapace; one-segmented protopods; biramous antennules and antennae; all trunk appendages similar; cephalic appendages large and raptorial; maxilliped somite fused to head; trunk unregionalized. Example: Speleonectes.

Class Cephalocarida

(sef´a-lo-kar´i-da) (Gr. kephale, head, + karis, shrimp, + ida, pl. suffix). No carapace; phyllopodia, one-segmented protopods; uniramous antennules and biramous antennae; compound eyes lacking; no abdominal appendages; maxilliped similar to thoracic leg. Example: Hutchinsoniella.

Class Branchiopoda

(bran´kee-op´oda) (Gr. branchia, gills, + pous, podos, foot). Phyllopodia; carapace present or absent; no maxillipeds; antennules reduced; compound eyes present; no abdominal appendages; maxillae reduced.

Class Maxillopoda (maks-i-lah´po-da) (L. maxilla, the jawbone, + pous, podos, a foot). Usually five cephalic, six thoracic, and four abdominal somites plus a telson, but reductions common; no typical appendages on abdomen; naupliar eye of unique structure (maxillopodan eye); carapace present or absent.

Class Malacostraca (mal-a-kos´tra-ka) (Gr. malakos, soft, + ostrakon, shell). Usually with eight somites in thorax and six plus telson in abdomen; all segments with appendages; antennules often biramous; first one to three thoracic appendages often maxillipeds; carapace covering head and part or all of thorax, sometimes absent; gills usually thoracic epipods.

Crustaceans are an extensive group with many subdivisions. They have many structures, habitats, and modes of living. Some are much larger than crayfishes; others are smaller, even microscopic. Some are highly developed and specialized; others have simpler organization.

Class Remipedia

Remipedia (Figure 19-14) is a very small, recently described class of Crustacea. The 10 species described so far have come from caves with connections to the sea. Remipedes have some very primitive features. There are 25 to 38 trunk segments (thorax and abdomen), all bearing paired, biramous, swimming appendages that are all essentially alike. Antennules are biramous. Both pairs of maxillae and a pair of maxillipeds, however, are prehensile and apparently adapted for feeding. The shape of the swimming appendages is similar to that found in Copepoda, but unlike copepods and cephalocarids, swimming legs are directed laterally rather than ventrally.

Class Cephalocarida

Cephalocarida (Figure 19-15) is also a small group, with only nine species known. Cephalocarids occur along both coasts of the United States, in the West Indies, and in Japan. They are 2 to 3 mm long and have been found in bottom sediments from the intertidal zone to a depth of 300 m. Some of their features are quite primitive. Thoracic limbs are very similar to each other, and second maxillae are similar to thoracic limbs. The second maxillae and the first seven thoracic legs have a large epipod on their protopod, and the protopod is a single joint. Cephalocarids have no eyes, carapace, or abdominal appendages. True hermaphrodites, they are unique among Arthropoda in discharging both eggs and sperm through a common duct.

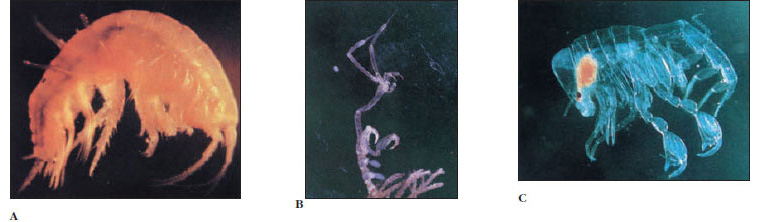

Figure 19-16 Examples of class Branchiopoda. A) Tadpole shrimp, order Notostraca; B) Fairy shrimp, order Anostraca; C) Daphnia, order Cladocera.

Branchiopoda also represents a crustacean type with some primitive characters. Four orders are recognized: Anostraca (fairy shrimp and brine shrimp, Figure 19-16B), with no carapace; Notostraca (tadpole shrimp, Figure 19-16A), whose carapace forms a large dorsal shield; Conchostraca (clam shrimp), with a bivalve carapace usually enclosing the entire body; and Cladocera (water fleas, Figure 19-16C), typically with a carapace that encloses the body but not the head. Branchiopods have reduced first antennae and second maxillae. Their legs are flattened and leaflike (phyllopodia) and are the chief respiratory organs (hence the name branchiopods). Most branchiopods also use their legs for suspension feeding, and in groups other than the cladocerans, they use their legs for locomotion as well.

Most branchiopods are freshwater forms. The most important and abundant order is Cladocera, which often forms a large segment of freshwater zooplankton. Their reproduction is very interesting and is reminiscent of that occurring in some rotifers (Pseudocoelomate Animals). During summer they often produce only females, by parthenogenesis, rapidly increasing the population.

With the onset of unfavorable conditions, some males are produced, and eggs that must be fertilized are produced by normal meiosis. Fertilized eggs are highly resistant to cold and desiccation, and they are very important for survival of the species over winter and for passive transfer to new habitats. Most cladocerans have direct development, whereas other branchiopods have gradual metamorphosis.

Figure 19-16 Examples of class Branchiopoda. A) Tadpole shrimp, order Notostraca; B) Fairy shrimp, order Anostraca; C) Daphnia, order Cladocera.

Class Maxillopoda

Class Maxillopoda includes a number of crustacean groups traditionally considered classes themselves. Specialists have recognized evidence that these groups descended from a common ancestor and thus form a monophyletic group within Crustacea. They basically have five cephalic, six thoracic, and usually four abdominal somites plus a telson, but reductions are common. There are no typical appendages on the abdomen. The eye of the nauplius (when present) has a unique structure and is referred to as a maxillopodan eye.

Subclass Ostracoda

Members of Ostracoda are, like conchostracans, enclosed in a bivalve carapace and resemble tiny clams, 0.25 to 8 mm long (Figure 19-17). Ostracods show considerable fusion of trunk somites, and numbers of thoracic appendages are reduced to two or none. Feeding and locomotion are principally by use of the head appendages. Most ostracods live on the bottom or climb on plants, but some are planktonic or burrowing, and a few are parasitic. Feeding habits are diverse; there are particle, plant, and carrion feeders and predators. They are widespread in both marine and freshwater habitats. Development is gradual metamorphosis.

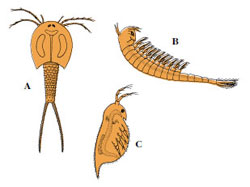

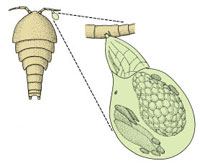

Figure 19-18 A mystacocarid crustacean of subclass Mystacocarida, class Maxillopoda.

Figure 19-19 A copepod with attached ovisacs; subclass Copepoda, class Maxillopoda.

Subclass Copepoda

This group is second only to Malacostraca in numbers of species. Copepods are small (usually a few millimeters or less in length) and rather elongate, tapering toward the posterior. They lack a carapace and retain the simple, median, nauplius (maxillopodan) eye in adults (Figure 19-19). They have a single pair of uniramous maxillipeds and four pairs of rather flattened, biramous, thoracic swimming appendages. The fifth pair of legs is reduced. The posterior part of the body is usually separated from the anterior, appendage-bearing portion by a major articulation. Antennules are often longer than other appendages. Copepoda have become very diverse and evolutionarily enterprising, with large numbers of symbiotic as well as freeliving species. Many parasites are highly modified, and adults may be so highly modified (and may depart so far from the description just given) that they can hardly be recognized as arthropods, let alone crustaceans.

Ecologically, free-living copepods are of extreme importance, often dominating the primary consumer level in aquatic communities. In many marine localities the copepod Calanus is the most abundant organism in the zooplankton and has the greatest proportion of the total biomass. In other localities it may be surpassed in the biomass only by euphausids. Calanus forms a major portion of the diet of such economically and ecologically important fish as herring, menhaden, sardines, and larvae of larger fish and (along with euphausids) is an important food item for some whales and sharks. Other genera commonly occur in marine zooplankton, and some forms such as Cyclops and Diaptomus may form an important segment of freshwater plankton. Many species of copepods are parasites of a wide variety of other marine invertebrates and marine and freshwater fish, and some of the latter are of economic importance. Some species of free-living copepods serve as intermediate hosts of parasites of humans, such as Diphyllobothrium (a tapeworm) and Dracunculus (a nematode), and of other animals.

Development in copepods is indirect, and some highly modified parasites show striking metamorphoses.

Figure 19-18 A mystacocarid crustacean of subclass Mystacocarida, class Maxillopoda.

Figure 19-19 A copepod with attached ovisacs; subclass Copepoda, class Maxillopoda.

Subclass Tantulocarida

Figure 19-20 A tantulocarid. This curious little parasite is shown attached to the first antenna of its copepod host at left; subclass Tantulocarida, class Maxillopoda.

Figure 19-20 A tantulocarid. This curious little parasite is shown attached to the first antenna of its copepod host at left; subclass Tantulocarida, class Maxillopoda.

Subclass Branchiura

Branchiurans are a small group of primarily fish parasites, which, despite their name, have no gills (Figure 19-21). Members of this group are usually between 5 and 10 mm long and may be found on marine or freshwater fish. They typically have a broad, shieldlike carapace, compound eyes, four biramous thoracic appendages for swimming, and a short, unsegmented abdomen. Second maxillae have become modified as suction cups, enabling the parasites to move about on their fish host or even from fish to fish. Development is almost direct: there is no nauplius, and young resemble adults except in size and degree of development of appendages.

Subclass Cirripedia

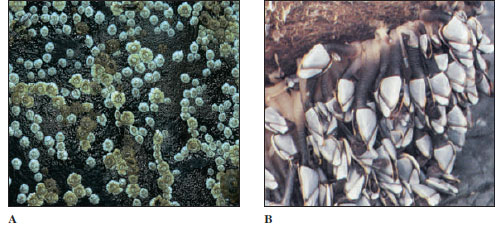

Cirripedia includes barnacles (order Thoracica), which are usually enclosed in a shell of calcareous plates, as well as three smaller orders of burrowing or parasitic forms. Barnacles are sessile as adults and may be attached to the substrate by a stalk (gooseneck barnacles) (Figure 19-22B) or directly (acorn barnacles) (Figure 19-22A). Typically the carapace (mantle) surrounds the body and secretes a shell of calcareous plates. The head is reduced, the abdomen is absent, and the thoracic legs are long, many-jointed cirri with hairlike setae. The cirri are extended through an opening between the calcareous plates to filter from the water the small particles on which the animal feeds (Figure 19-22). Although all barnacles are marine, they are often found in the intertidal zone and are therefore exposed to drying and sometimes fresh water for some periods of time. During these periods the aperture between the plates closes to a very narrow slit.

Figure 19-22 Barnacles; order Thoracica, subclass Cirripedia, class Maxillopoda. A, Acorn barnacles, Balanus balanoides, on an intertidal rock await the return of the tide. B, Common gooseneck barnacles, Lepas anatifera. Note the feeding legs, or cirri, on Lepas. Barnacles attach themselves to a variety of firm substrates, including rocks, pilings, and boat bottoms.

Barnacles are hermaphroditic and undergo a striking metamorphosis during development. Most hatch as nauplii, which soon become cyprid larvae, so called because of their resemblance to an ostracod genus Cypris. They have a bivalve carapace and compound eyes. Cyprids attach to the substrate by means of their first antennae, which have adhesive glands, and begin their metamorphosis. This involves several dramatic changes, including secretion of the calcareous plates, loss of eyes, and transformation of the swimming appendages to cirri.

Members of order Rhizocephala, such as Sacculina, are highly modified parasites of crabs. They start life as cyprid larvae, just as other cirripedes, but when they find a host, most species metamorphose into a kentrogon (Gr. kentron, a point, spine, + gonos, progeny) which injects cells of the parasite into the hemocoel of the crab (Figure 19-23). Eventually, rootlike absorptive processes grow throughout the crab’s body, and the parasite’s reproductive structures become externalized between the cephalothorax and the reflexed abdomen of the crab.

Class Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the largest class of Crustacea and shows great diversity. The diversity is indicated by the higher classification of the group, which includes three subclasses, 14 orders, and many suborders, infraorders, and superfamilies. We confine our coverage to mentioning a few of the most important orders.

Order Isopoda

Isopods are one of the few crustacean groups to have successfully invaded terrestrial habitats in addition to freshwater and seawater habitats and the only crustaceans to have become truly terrestrial.

They are commonly dorsoventrally flattened, lack a carapace, and have sessile compound eyes; maxillipeds are their first pair of thoracic limbs. The remaining thoracic limbs lack exopods and are similar, while the abdominal appendages bear the gills and, except the uropods, also are similar to each other (hence the name isopods).

Common land forms are the sow bugs, or pill bugs (Porcellio and Armadillidium, Figure 19-24A), which live under stones and in damp places. Although they are terrestrial, they do lack an efficient cuticular covering and other adaptations possessed by insects to conserve water; therefore they must live in moist conditions. Caecidotea (Figure 19-24B) is a common freshwater form found under rocks and among aquatic plants. Ligia is a common marine form that scurries about on the beach or rocky shore. Some isopods are parasites of fish (Figure 19-25) or crustaceans and some are highly modified. Development is essentially direct but may be highly metamorphic in specialized parasites.

Order Amphipoda

Amphipods resemble isopods in that the members lack a carapace and have sessile compound eyes and one pair of maxillipeds (Figure 19-26). However, they are usually compressed laterally, and their gills are in the typical thoracic position. Furthermore, their thoracic and abdominal limbs are each arranged in two or more groups that differ in form and function. For example, one group of abdominal legs may be for swimming and another for jumping. There are many marine amphipods, including some beachdwelling forms (for example, Orchestia, a beach hopper), numerous freshwater genera (Hyalella and Gammarus), and a few parasites. Development is direct.

Figure 19-26 Marine amphipods. A) Free-swimming amphipod, Anisogammarus sp. B) Skeleton shrimp, Caprella sp., shown on a bryozoan colony, resemble praying mantids. C) Phronima, a marine pelagic amphipod, takes over the tunic of a salp (subphylum Urochordata, Chordates). Swimming by means of its abdominal swimmerets, which protrude from the opening of the barrel-shaped tunic, the amphipod maneuvers to catch its prey. The tunic is not seen. (order Amphipoda, class Malacostraca)

Order Euphausiacea

Euphausiacea is a group of only about 90 species, but they are important as the oceanic plankton known as “krill” (Figure 19-27). They are about 3 to 6 cm long, have a carapace that is fused with all thoracic segments but does not entirely enclose the gills, have no maxillipeds, and have all thoracic limbs with exopods. Most are bioluminescent, with a light-producing substance in an organ called a photophore. Some species may occur in enormous swarms, covering up to 45 m2 and extending up to 500 m in one direction. They form a major portion of the diet of baleen whales and many fishes. Eggs hatch as nauplii, and development is indirect.

Figure 19-29 Sponge crab, Dromidia antillensis. This crab is one of several species that deliberately mask themselves with material from their immediate environment.

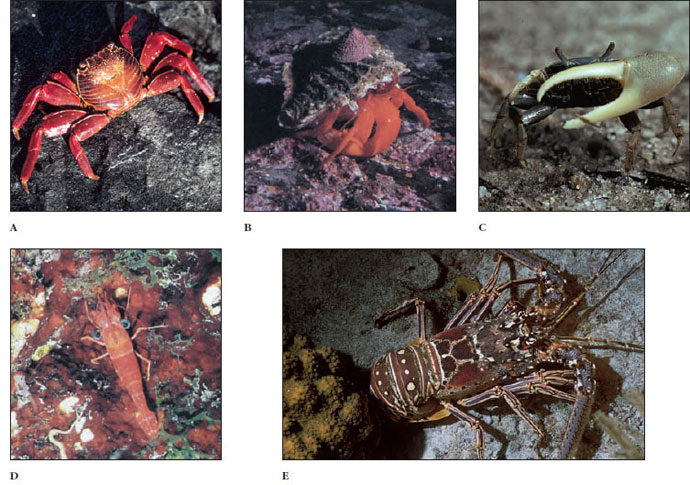

Decapods have three pairs of maxillipeds and five pairs of walking legs, of which the first is modified in many to form pincers (chelae). They range in size from a few millimeters to the largest of all arthropods, Japanese spider crabs, whose chelae span 4 m. Crayfishes, lobsters, crabs, and “true” shrimp belong in this group (Figures 19-28 and 19-29). There are about 10,000 species of decapods, and the order is extremely diverse. They are very important ecologically and economically, and numerous species are relished as items of food for humans.

Crabs, especially, exist in a great variety of forms. Although resembling crayfishes, they differ from the latter in having a broader cephalothorax and reduced abdomen. Familiar examples along the seashore are hermit crabs (Figure 19-28B), which live in snail shells because their abdomens are not protected by the same heavy exoskeleton as are the anterior parts, fiddler crabs, Uca (Figure 19-28C), which burrow in sand just below the high-tide level and come out to run about over the sand while the tide is out; and spider crabs such as Libinia and interesting decorator crabs Oregonia and others, which cover their carapaces with sponges and sea anemones for protective camouflage (Figure 19-29).

Figure 19-29 Sponge crab, Dromidia antillensis. This crab is one of several species that deliberately mask themselves with material from their immediate environment.

Figure 19-28 Decapod crustaceans. A) A bright orange tropical rock crab, Grapsus grapsus, is a conspicuous exception to the rule that most crabs bear cryptic coloration. B) A hermit crab, Elassochirus gilli, which has a soft abdominal exoskeleton, lives in a snail shell that it carries about and into which it can withdraw for protection. C) A male fiddler crab, Uca sp., uses its enlarged cheliped to wave territorial displays and in threat and combat. D) A red night shrimp, Rhynchocinetes rigens, prowls caves and overhangs of coral reefs, but only at night. E) A spiny lobster, Panulirus argus, (shown here) and the northern lobster, Homarus americanus, are consumed with gusto by many people. (order Decapoda, class Malacostraca)

Classification of Subphylum Crustacea

Higher classification of Crustacea is complex and subject to change as new data become available. The following relies on several sources. We are omitting many smaller taxa.

Class Remipedia

(ri-mi-pee´dee-a) (L. remipedes, oar-footed). No carapace; one-segmented protopods; biramous antennules and antennae; all trunk appendages similar; cephalic appendages large and raptorial; maxilliped somite fused to head; trunk unregionalized. Example: Speleonectes.

Class Cephalocarida

(sef´a-lo-kar´i-da) (Gr. kephale, head, + karis, shrimp, + ida, pl. suffix). No carapace; phyllopodia, one-segmented protopods; uniramous antennules and biramous antennae; compound eyes lacking; no abdominal appendages; maxilliped similar to thoracic leg. Example: Hutchinsoniella.

Class Branchiopoda

(bran´kee-op´oda) (Gr. branchia, gills, + pous, podos, foot). Phyllopodia; carapace present or absent; no maxillipeds; antennules reduced; compound eyes present; no abdominal appendages; maxillae reduced.

- Order Anostraca (an-os´tra-ka) Gr. an-, prefix meaning without, + ostrakon, shell): fairy shrimp and brine shrimp. No carapace; no abdominal appendages; uniramous antennae. Examples: Artemia, Branchinecta.

Order Notostraca (no-tos´tra-ka) (Gr. notos, the back, + ostrakon, shell): tadpole shrimp. Carapace forming large dorsal shield; abdominal appendages present, reduced posteriorly; antennae vestigial. Examples: Triops, Lepidurus.

Order Cladocera (kla-dah´se-ra) (Gr. klados, a branch, + keras, a horn): water fleas. Carapace folded, usually enclosing trunk but not head; biramous antennae; abdominal appendages absent. Examples: Daphnia, Leptodora.

Order Conchostraca (konkos ´tra-ka) (Gr. konche, shell + ostrakon, shell): clam shrimp. Bivalved carapace enclosing entire body; biramous antennae; all trunk appendages similar. Example: Lynceus.

Class Maxillopoda (maks-i-lah´po-da) (L. maxilla, the jawbone, + pous, podos, a foot). Usually five cephalic, six thoracic, and four abdominal somites plus a telson, but reductions common; no typical appendages on abdomen; naupliar eye of unique structure (maxillopodan eye); carapace present or absent.

- Subclass Ostracoda (os-trak´o-da) (Gr. ostrakodes, having a shell): ostracods. Bivalve carapace entirely encloses body; body unsegmented or indistinctly segmented; no more than two pairs of trunk appendages. Examples: Cypris, Cypridina, Gigantocypris.

Subclass Mystacocarida (mis-tak´okar´i-da) (Gr. mystax, mustache, + karis, shrimp, + ida, pl. suffix): mustache shrimps. No carapace; body of cephalon and ten-segmented trunk; telson with clawlike caudal rami; cephalic appendages nearly identical, but antennae and mandibles biramous, other head appendages uniramous; second through fifth trunk somites with short, single-segment appendages. Example: Derocheilocaris.

Subclass Copepoda (ko-pep´o-da) (Gr. kope, oar, + pous, podos, foot): copepods. No carapace; thorax typically of seven somites, of which first and sometimes second fuse with head to form cephalothorax; antennules uniramous; antennae bi- or uniramous; four to five pairs swimming legs; parasitic forms often highly modified. Examples:Cyclops, Diaptomus, Calanus, Ergasilus, Lernaea, Salmincola, Caligus.

Subclass Tantulocarida (tan´tu-lokar ´i-da) (L. tantulus, so small, + caris, shrimp). No recognizable cephalic appendages except antennae on sexual female; solid median cephalic stylet; six free thoracic somites, each with pair of appendages, anterior five biramous; six abdominal somites; minute copepod-like ectoparasites. Examples: Basipodella, Deoterthron.

Subclass Branchiura (bran-ki-ur´a) (Gr. branchia, gills, + ura, tail): fish lice. Body oval, head and most of trunk covered by flattened carapace, incompletely fused to first thoracic somite; thorax with four pairs of appendages, biramous; abdomen unsegmented, bilobed; eyes compound; antennae and antennules reduced; maxillules often forming suctoral discs. Examples: Argulus, Chonopeltis.

Subclass Cirripedia (sir-i-ped&cute;i-a) (L. cirrus, curl of hair, + pes, pedis, foot): barnacles. Sessile or parasitic as adults; head reduced and abdomen rudimentary; paired compound eyes absent; body segmentation indistinct; usually hermaphroditic; in free-living forms carapace becomes mantle, which secretes calcareous plates; antennules become organs of attachment, then disappear. Examples: Balanus, Policipes, Sacculina.

Class Malacostraca (mal-a-kos´tra-ka) (Gr. malakos, soft, + ostrakon, shell). Usually with eight somites in thorax and six plus telson in abdomen; all segments with appendages; antennules often biramous; first one to three thoracic appendages often maxillipeds; carapace covering head and part or all of thorax, sometimes absent; gills usually thoracic epipods.

Order Isopoda (i-sop´o-da) (Gr. isos, equal, + pous, podos, foot): isopods. No carapace; antennules usually uniramous, sometimes vestigial; eyes sessile (not stalked); gills on abdominal appendages; body commonly dorso-ventrally flattened; second thoracic appendages usually not prehensile. Examples: Armadillidium, Caecidotea, Ligia, Porcellio.

Order Amphipoda (am-fip´o-da) (Gr. amphis, on both sides, + pous, podos, foot): amphipods. No carapace; antennules often biramous; eyes usually sessile; gills on thoracic coxae; second and third thoracic limbs usually prehensile; typically bilaterally compressed body form. Examples: Orchestia, Hyalella, Gammarus.

Order Euphausiacea (yu-faws-ia ´si-a) (Gr. eu, well, + phausi, shining bright, + L. acea, suffix, pertaining to): krill. Carapace fused to all thoracic segments but not entirely enclosing gills, no maxillipeds; all thoracic limbs with exopods. Example: Meganyctiphanes.

Order Decapoda (de-kap´o-da) (Gr. deka, ten, pous, podos, foot): shrimps, crabs, lobsters. All thoracic segments fused with and covered by carapace; eyes on stalks; first three pairs of thoracic appendages modified to maxillipeds. Examples: Penaeus, Cancer, Pagurus, Grapsus, Homarus, Panulirus.