Phylogeny and Adaptive Radiation

Phylogeny and

Adaptive Radiation

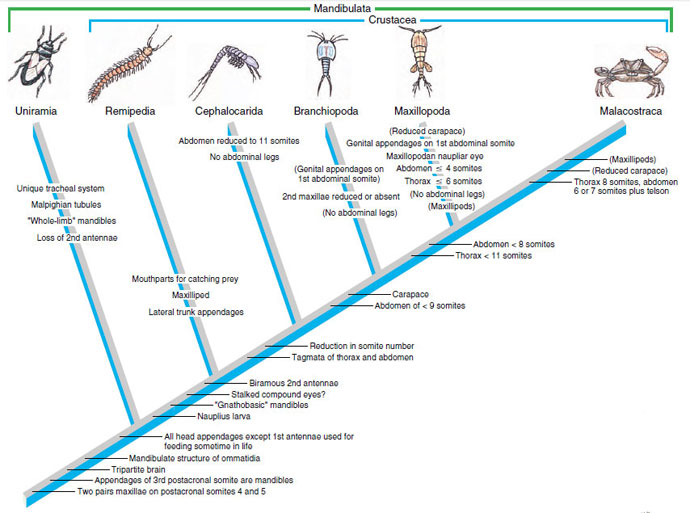

Phylogeny The relationship of crustaceans to other arthropods has long been a puzzle. The controversy over whether Arthropoda is polyphyletic was mentioned in Arthropods . Crustaceans have traditionally been allied with uniramians (insects, myriapods, see Terrestrial Mandibulates) in a group known as Mandibulata because they both have mandibles, as contrasted with chelicerae. Critics of this traditional grouping have argued that the mandibles in each group are so different that they could not have been inherited from a common ancestor. In addition to some differences in the muscles, mandibles of crustaceans are multijointed, and chewing and biting surfaces are at the bases (“gnathobasic mandible”). Uniramian mandibles, on the other hand, are of a single joint, and the biting surface is on the distal portion (“entire limb mandible”). However, advocates of the “mandibulate hypothesis” maintain that these differences are not so fundamental that they could not have arisen during the 550-million-year history of mandibulate taxa. They also emphasize the numerous other similarities between crustaceans and uniramians, such as basic structure of ommatidia, tripartite brain, and head primitively of five somites, each with a pair of appendages. This mandibulate hypothesis can be depicted in a cladogram (Figure 19-30).

Among Crustacea, Remipedia seem to be the most primitive in many characteristics (Figure 19-30). They have a long body, with no tagmatization behind the head, a double ventral nerve cord, and serially arranged digestive ceca. Fossils of a puzzling arthropod from the Mississippian period seem to be the sister group of remipedians and may shed light on the origin of biramous appendages. They have two pairs of uniramous limbs on each somite. It is possible that each somite actually represents two ancestral somites that fused (diplopodous condition).* We see such a condition in Diplopoda, a uniramian class with two pairs of legs on each somite. In ancestral crustaceans, the bases of the pairs of limbs on diplopodous somites would have fused together to become a biramous appendage, with two branches on a common protopod.

Adaptive Radiation

Adaptive radiation demonstrated by crustaceans is great, with all manner of aquatic niches exploited. They are unquestionably the dominant arthropod group in marine environments, and they share dominance of freshwater habitats with insects. Invasions of terrestrial environments have been much more limited, with isopods being the only notable success. There are a few other terrestrial examples, such as land crabs. The most diverse class is Malacostraca, and the most abundant group is Copepoda. Members of both taxa include planktonic suspension feeders and numerous scavengers. Copepods have been particularly successful as parasites of both vertebrates and invertebrates, and it is clear that present parasitic copepods are products of numerous invasions of such niches.

Phylogeny The relationship of crustaceans to other arthropods has long been a puzzle. The controversy over whether Arthropoda is polyphyletic was mentioned in Arthropods . Crustaceans have traditionally been allied with uniramians (insects, myriapods, see Terrestrial Mandibulates) in a group known as Mandibulata because they both have mandibles, as contrasted with chelicerae. Critics of this traditional grouping have argued that the mandibles in each group are so different that they could not have been inherited from a common ancestor. In addition to some differences in the muscles, mandibles of crustaceans are multijointed, and chewing and biting surfaces are at the bases (“gnathobasic mandible”). Uniramian mandibles, on the other hand, are of a single joint, and the biting surface is on the distal portion (“entire limb mandible”). However, advocates of the “mandibulate hypothesis” maintain that these differences are not so fundamental that they could not have arisen during the 550-million-year history of mandibulate taxa. They also emphasize the numerous other similarities between crustaceans and uniramians, such as basic structure of ommatidia, tripartite brain, and head primitively of five somites, each with a pair of appendages. This mandibulate hypothesis can be depicted in a cladogram (Figure 19-30).

Among Crustacea, Remipedia seem to be the most primitive in many characteristics (Figure 19-30). They have a long body, with no tagmatization behind the head, a double ventral nerve cord, and serially arranged digestive ceca. Fossils of a puzzling arthropod from the Mississippian period seem to be the sister group of remipedians and may shed light on the origin of biramous appendages. They have two pairs of uniramous limbs on each somite. It is possible that each somite actually represents two ancestral somites that fused (diplopodous condition).* We see such a condition in Diplopoda, a uniramian class with two pairs of legs on each somite. In ancestral crustaceans, the bases of the pairs of limbs on diplopodous somites would have fused together to become a biramous appendage, with two branches on a common protopod.

|

| Figure 19-30 Cladogram showing hypothetical ancestordescendant relationships of uniramians and classes of crustaceans. Uniramians and crustaceans (mandibulates) are hypothetical sister groups evolving from a common ancestor defined by numerous shared derived characteristics. Characters followed by a question mark may be primitive rather than shared derived features. The acron corresponds to the prostomium of the annelids and is the anterior closure, not counted as a somite. Characters in parentheses presumably originated within the group subsequent to the origin of the group itself. These would thus be examples of parallel or convergent features that arose in more than one class. |

Adaptive Radiation

Adaptive radiation demonstrated by crustaceans is great, with all manner of aquatic niches exploited. They are unquestionably the dominant arthropod group in marine environments, and they share dominance of freshwater habitats with insects. Invasions of terrestrial environments have been much more limited, with isopods being the only notable success. There are a few other terrestrial examples, such as land crabs. The most diverse class is Malacostraca, and the most abundant group is Copepoda. Members of both taxa include planktonic suspension feeders and numerous scavengers. Copepods have been particularly successful as parasites of both vertebrates and invertebrates, and it is clear that present parasitic copepods are products of numerous invasions of such niches.