Arteries

|

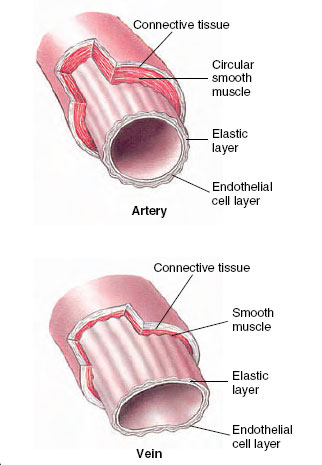

| Figure 33-15 Artery and vein, showing layers. Note greater thickness of the muscularis layer (tunica media) in the artery. |

Arteries

All vessels leaving the heart are called arteries whether they carry oxygenated blood (aorta) or deoxygenated blood (pulmonary artery). To withstand high, pounding pressures, arteries are invested with layers of both elastic and tough inelastic connective fibers (Figure 33-15). The elasticity of arteries allows them to yield to the surge of blood leaving the heart during ventricular systole and then to compress the fluid column during ventricular diastole. This elasticity prevents large changes in blood pressure. Thus the normal arterial pressure in humans varies only between 120 mm Hg (systole) and 80 mm Hg (diastole) (usually expressed as 120/80 or 120 over 80), rather than dropping to zero during diastole as we might expect in a fluid system with an intermittent pump.

As arteries branch and narrow into arterioles, the walls become mostly smooth muscle. Contraction of this muscle narrows the arterioles and reduces the flow of blood. Arterioles thus control blood flow to body organs, diverting it to where it is most needed. Blood must be pumped with a hydrostatic pressure sufficient to overcome resistance of the narrow passages through which it must flow. Consequently, large animals tend to have higher blood pressure than do small animals.

Blood pressure was first measured in 1733 by Stephan Hales, an English clergyman with unusual inventiveness and curiosity. He tied his mare, which was “to have been killed as unfit for service,” on her back and exposed the femoral artery. This he cannulated with a brass tube, connecting it to a tall glass tube with the windpipe of a goose. The use of the windpipe was both imaginative and practical; it gave the apparatus flexibility “to avoid inconveniences that might arise if the mare struggled.” The blood rose 8 feet in the glass tube and bobbed up and down with systolic and diastolic beats of the heart. The weight of the 8-foot column of blood was equal to the blood pressure. We now express blood pressure as the height of a column of mercury (Hg), which is 13.6 times heavier than water. Hales’ figures, expressed in millimeters of mercury, indicate that he measured a blood pressure of 180 to 200 mm Hg, about normal for a horse.

Today, we measure blood pressure in humans most commonly and easily with an instrument called a sphygmomanometer. We inflate a cuff on the upper arm with air to a pressure sufficient to close the arteries in the arm. Holding a stethoscope over the brachial artery (in the crook of the elbow) and slowly releasing air from the cuff, we can hear the first spurts of blood through the artery as it opens slightly. This is equivalent to systolic pressure. As pressure in the cuff decreases, the sound finally disappears as blood runs smoothly through the artery. The pressure at which the sound disappears is diastolic pressure.