Linnaeus and the Development of Classification

Linnaeus and the Development of Classification

The Greek philosopher and biologist Aristotle was the first to classify organisms on the basis of their structural similarities. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the English naturalist John Ray (1627 to 1705) introduced a more comprehensive system of classification and a new concept of species. The flowering of systematics in the eighteenth century culminated in the work of Carolus Linnaeus (1707 to 1778; Figure 10-1), who gave us our current scheme of classification.

Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist at the University of Uppsala. He had a Carolus Linnaeus (1707 to 1778). This portrait was made of Linnaeus at age 68, three years before his death.

great talent for collecting and classifying objects, especially flowers. Linnaeus produced an extensive system of classification for both plants and animals. This scheme, published in his great work, Systema Naturae, used morphology (the comparative study of organismal form) for arranging specimens in collections. He divided the animal kingdom into species and gave each one a distinctive name. He grouped species into genera, genera into orders, and orders into classes. Because his knowledge of animals was limited, his lower categories, such as genera, often were very broad and included animals that are only distantly related. Much of his classification has been drastically altered, but the basic principle of his scheme is still followed.

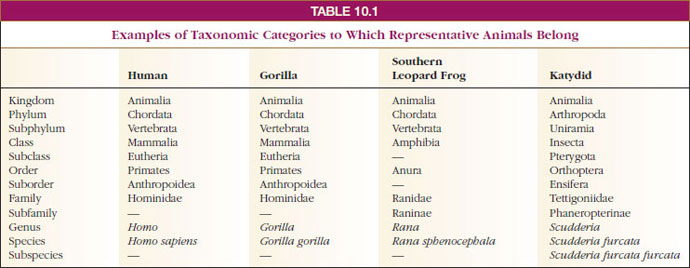

Linnaeus’s scheme of arranging organisms into an ascending series of groups of ever-increasing inclusiveness is a hierarchical system of classification. Major categories, or taxa (sing., taxon), into which organisms are grouped were given one of several standard taxonomic ranks to indicate the general degree of inclusiveness of the group. The hierarchy of taxonomic ranks has been expanded considerably since Linnaeus’s time (Table 10-1). It now includes seven mandatory ranks for the animal kingdom, in descending series: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. All organisms being classified must be placed into at least seven taxa, one at each of the mandatory ranks. Taxonomists have the option of subdividing these seven ranks further to recognize more than seven taxa (superclass, subclass, infraclass, superorder, suborder, etc.) for any particular group of organisms. In all, more than 30 taxonomic ranks are recognized. For very large and complex groups, such as fishes and insects, these additional ranks are needed to express different degrees of evolutionary divergence. Unfortunately, they also contribute complexity to the system.

Linnaeus’s system for naming species is known as binomial nomenclature. Each species has a latinized name composed of two words (hence binomial) written in italics (underlined if handwritten or typed). The first word is the name of the genus, written with a capital initial letter; the second word is the species epithet, which is peculiar to the species within the genus and is written with a small initial letter (see Table 10- 1). The genus name is always a noun, and the species epithet is usually an adjective that must agree in gender with the genus. For instance, the scientific name of the common robin is Turdus migratorius (L. turdus, thrush; migratorius, of migratory habit). The species epithet never stands alone; the complete binomial must be used to name a species. Names of genera must refer only to single groups of organisms; the same name cannot be given to two different genera of animals. The same species epithet may be used in different genera, however, to denote different and unrelated species. For example, the scientific name of the white-breasted nuthatch is Sitta carolinensis. The species epithet “carolinensis” is used in other genera, including Parus carolinensis (Carolina chickadee) and Anolis carolinensis (green anole, a lizard) to mean “of Carolina.” All ranks above the species are designated using uninomial nouns, written with a capital initial letter.

|

| Figure 10-1 Carolus Linnaeus (1707 to 1778). This portrait was made of Linnaeus at age 68, three years before his death. |

The Greek philosopher and biologist Aristotle was the first to classify organisms on the basis of their structural similarities. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the English naturalist John Ray (1627 to 1705) introduced a more comprehensive system of classification and a new concept of species. The flowering of systematics in the eighteenth century culminated in the work of Carolus Linnaeus (1707 to 1778; Figure 10-1), who gave us our current scheme of classification.

Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist at the University of Uppsala. He had a Carolus Linnaeus (1707 to 1778). This portrait was made of Linnaeus at age 68, three years before his death.

great talent for collecting and classifying objects, especially flowers. Linnaeus produced an extensive system of classification for both plants and animals. This scheme, published in his great work, Systema Naturae, used morphology (the comparative study of organismal form) for arranging specimens in collections. He divided the animal kingdom into species and gave each one a distinctive name. He grouped species into genera, genera into orders, and orders into classes. Because his knowledge of animals was limited, his lower categories, such as genera, often were very broad and included animals that are only distantly related. Much of his classification has been drastically altered, but the basic principle of his scheme is still followed.

Linnaeus’s scheme of arranging organisms into an ascending series of groups of ever-increasing inclusiveness is a hierarchical system of classification. Major categories, or taxa (sing., taxon), into which organisms are grouped were given one of several standard taxonomic ranks to indicate the general degree of inclusiveness of the group. The hierarchy of taxonomic ranks has been expanded considerably since Linnaeus’s time (Table 10-1). It now includes seven mandatory ranks for the animal kingdom, in descending series: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. All organisms being classified must be placed into at least seven taxa, one at each of the mandatory ranks. Taxonomists have the option of subdividing these seven ranks further to recognize more than seven taxa (superclass, subclass, infraclass, superorder, suborder, etc.) for any particular group of organisms. In all, more than 30 taxonomic ranks are recognized. For very large and complex groups, such as fishes and insects, these additional ranks are needed to express different degrees of evolutionary divergence. Unfortunately, they also contribute complexity to the system.

Linnaeus’s system for naming species is known as binomial nomenclature. Each species has a latinized name composed of two words (hence binomial) written in italics (underlined if handwritten or typed). The first word is the name of the genus, written with a capital initial letter; the second word is the species epithet, which is peculiar to the species within the genus and is written with a small initial letter (see Table 10- 1). The genus name is always a noun, and the species epithet is usually an adjective that must agree in gender with the genus. For instance, the scientific name of the common robin is Turdus migratorius (L. turdus, thrush; migratorius, of migratory habit). The species epithet never stands alone; the complete binomial must be used to name a species. Names of genera must refer only to single groups of organisms; the same name cannot be given to two different genera of animals. The same species epithet may be used in different genera, however, to denote different and unrelated species. For example, the scientific name of the white-breasted nuthatch is Sitta carolinensis. The species epithet “carolinensis” is used in other genera, including Parus carolinensis (Carolina chickadee) and Anolis carolinensis (green anole, a lizard) to mean “of Carolina.” All ranks above the species are designated using uninomial nouns, written with a capital initial letter.

|

| TABLE 10.1 |