Phylum Brachiopoda

Phylum

Brachiopoda

Brachiopoda (brak-i-op´o-da) (Gr. brachion, arm, + pous, podos, foot), or lamp shells, are an ancient group.

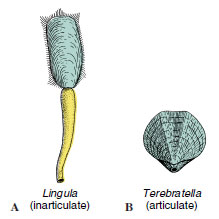

Although about 325 species are now living, some 12,000 fossil species, which once flourished in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic seas, have been described. Modern forms have changed little from early ones. The genus Lingula (L. tongue) (Figure 22-7A) is probably the most ancient of these “living fossils,” having existed virtually unchanged since Ordovician times. Most modern brachiopod shells range between 5 to 80 mm in length, but some fossil forms reached 30 cm.

Brachiopods are attached, bottomdwelling, marine forms that mostly prefer shallow water. Externally brachiopods resemble bivalved molluscs in having two calcareous shell valves secreted by a mantle. They were, in fact, classed with molluscs until the middle of the nineteenth century, and their name refers to the arms of the lophophore, which were thought homologous to the mollusc foot. Brachiopods, however, have dorsal and ventral valves instead of right and left lateral valves as do bivalve molluscs and, unlike bivalves, most of them are attached to a substrate either directly or by means of a fleshy stalk called a pedicel (or pedicle). Some, such as Lingula, live in vertical burrows in sand or mud. Muscles open and close the valves and provide movement for the stalk and tentacles.

In most brachiopods the ventral (pedicel) valve is slightly larger than the dorsal (brachial) valve, and one end projects in the form of a short, pointed beak that is perforated where the fleshy stalk passes through the shell to attach to the substratum (Figure 22-7B). In many the shape of the pedicel valve is like that of a classic oil lamp of ancient Greece and Rome, so that brachiopods came to be known as “lamp shells.”

There are two classes of brachiopods, based on shell structure. Shell valves of Articulata have a connecting hinge with an interlocking tooth-and-socket arrangement, as in Terebratella (L. terebratus, a boring, + ella, dim. suffix); those of Inarticulata lack the hinge and are held together by muscles only, as in Lingula and Glottidia (Gr. glottidos, mouth of windpipe).

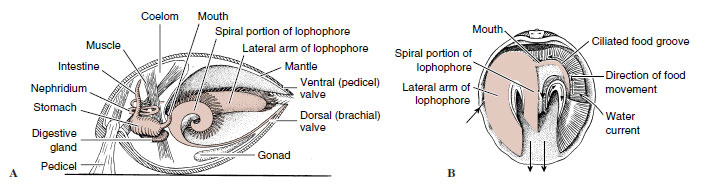

The body occupies only the posterior part of the space between the valves (Figure 22-8), and extensions of the body wall form mantle lobes that line and secrete the shell. The large horseshoe-shaped lophophore in the anterior mantle cavity bears long, ciliated tentacles used in respiration and feeding. Ciliary water currents carry food particles between the gaping valves and over the lophophore. The tentacles catch food particles, and ciliated grooves carry the particles along the arm of the lophophore to the mouth. Rejection tracts carry unwanted particles to the mantle lobe where they are swept out in ciliary currents. Organic detritus and some algae are apparently the primary food sources. The brachiopod lophophore not only can create food currents, as do other lophophorates, but also seems able to absorb dissolved nutrients directly from environmental seawater.

There is no cavity in the epistome of articulates, but in inarticulates there is a protocoel in the epistome that opens into the mesocoel. As in other lophophorates, the posterior metacoel bears the viscera. One or two pairs of nephridia open into the coelom and empty into the mantle cavity. Coelomocytes, which ingest particulate wastes, are expelled by the nephridia. There is an open circulatory system with a contractile heart. The lophophore and mantle are probably the chief sites of gaseous exchange. There is a nerve ring with a small dorsal and a larger ventral ganglion.

Sexes are separate, and paired gonads discharge gametes through the nephridia. Most fertilization is external, but a few species brood their eggs and young.

Cleavage is radial, and coelom and mesoderm formation in at least some brachiopods is enterocoelic. The blastopore closes, but its relationship to the mouth is uncertain. In articulates, metamorphosis of the larva occurs after it has attached by a pedicel. In inarticulates, juveniles resemble a minute brachiopod with a coiled pedicel in the mantle cavity. There is no metamorphosis. As the larva settles, the pedicel attaches to the substratum, and adult existence begins.

Brachiopoda (brak-i-op´o-da) (Gr. brachion, arm, + pous, podos, foot), or lamp shells, are an ancient group.

Although about 325 species are now living, some 12,000 fossil species, which once flourished in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic seas, have been described. Modern forms have changed little from early ones. The genus Lingula (L. tongue) (Figure 22-7A) is probably the most ancient of these “living fossils,” having existed virtually unchanged since Ordovician times. Most modern brachiopod shells range between 5 to 80 mm in length, but some fossil forms reached 30 cm.

|

| Figure 22-7 Brachiopods. A, Lingula, an inarticulate brachiopod that normally occupies a burrow. The contractile pedicel can withdraw the body into the burrow. B, An articulate brachiopod, Terebratella. The valves have a tooth-andsocket articulation, and a short pedicel projects through the pedicel valve to attach to the substratum. |

Brachiopods are attached, bottomdwelling, marine forms that mostly prefer shallow water. Externally brachiopods resemble bivalved molluscs in having two calcareous shell valves secreted by a mantle. They were, in fact, classed with molluscs until the middle of the nineteenth century, and their name refers to the arms of the lophophore, which were thought homologous to the mollusc foot. Brachiopods, however, have dorsal and ventral valves instead of right and left lateral valves as do bivalve molluscs and, unlike bivalves, most of them are attached to a substrate either directly or by means of a fleshy stalk called a pedicel (or pedicle). Some, such as Lingula, live in vertical burrows in sand or mud. Muscles open and close the valves and provide movement for the stalk and tentacles.

In most brachiopods the ventral (pedicel) valve is slightly larger than the dorsal (brachial) valve, and one end projects in the form of a short, pointed beak that is perforated where the fleshy stalk passes through the shell to attach to the substratum (Figure 22-7B). In many the shape of the pedicel valve is like that of a classic oil lamp of ancient Greece and Rome, so that brachiopods came to be known as “lamp shells.”

There are two classes of brachiopods, based on shell structure. Shell valves of Articulata have a connecting hinge with an interlocking tooth-and-socket arrangement, as in Terebratella (L. terebratus, a boring, + ella, dim. suffix); those of Inarticulata lack the hinge and are held together by muscles only, as in Lingula and Glottidia (Gr. glottidos, mouth of windpipe).

The body occupies only the posterior part of the space between the valves (Figure 22-8), and extensions of the body wall form mantle lobes that line and secrete the shell. The large horseshoe-shaped lophophore in the anterior mantle cavity bears long, ciliated tentacles used in respiration and feeding. Ciliary water currents carry food particles between the gaping valves and over the lophophore. The tentacles catch food particles, and ciliated grooves carry the particles along the arm of the lophophore to the mouth. Rejection tracts carry unwanted particles to the mantle lobe where they are swept out in ciliary currents. Organic detritus and some algae are apparently the primary food sources. The brachiopod lophophore not only can create food currents, as do other lophophorates, but also seems able to absorb dissolved nutrients directly from environmental seawater.

|

| Figure 22-8 Phylum Brachiopoda. A, An articulate brachiopod (longitudinal section). B, Feeding and respiratory currents. Large arrows show water flow over lophophore; small arrows indicate food movement toward mouth in ciliated food groove. |

There is no cavity in the epistome of articulates, but in inarticulates there is a protocoel in the epistome that opens into the mesocoel. As in other lophophorates, the posterior metacoel bears the viscera. One or two pairs of nephridia open into the coelom and empty into the mantle cavity. Coelomocytes, which ingest particulate wastes, are expelled by the nephridia. There is an open circulatory system with a contractile heart. The lophophore and mantle are probably the chief sites of gaseous exchange. There is a nerve ring with a small dorsal and a larger ventral ganglion.

Sexes are separate, and paired gonads discharge gametes through the nephridia. Most fertilization is external, but a few species brood their eggs and young.

Cleavage is radial, and coelom and mesoderm formation in at least some brachiopods is enterocoelic. The blastopore closes, but its relationship to the mouth is uncertain. In articulates, metamorphosis of the larva occurs after it has attached by a pedicel. In inarticulates, juveniles resemble a minute brachiopod with a coiled pedicel in the mantle cavity. There is no metamorphosis. As the larva settles, the pedicel attaches to the substratum, and adult existence begins.