Phylum Pogonophora

|

| Figure 21-6 A colony of giant beardworms (phylum Pogonophora) at great depth near a hydrothermal vent along the Galápagos Trench, eastern Pacific Ocean. |

Phylum Pogonophora

Phylum Pogonophora (po´go-nof´e-ra) (Gr. pogon, beard, + phora, bearing), or beardworms, was entirely unknown before the twentieth century. The first specimens to be described were collected from deep-sea dredgings off the coast of Indonesia in 1900. They have since been discovered in several seas, including the western Atlantic off the U.S. eastern coast. Some 145 species have been described so far. We recognize two classes, Perviata and Vestimentifera, but some authorities consider Vestimentifera a separate phylum. The usual length of perviatans is from 5 to 85 cm, with a diameter usually of less than a millimeter. Vestimentiferans, however, live around deepwater hydrothermal vents and grow much larger: up to 1.5 m long and 5 cm in diameter (Figure 21-6).

These elongated tube-dwelling forms have left no known fossil record. Their closest affinity seems to be to annelids.

Most pogonophores live in ooze on the ocean floor, always below the intertidal zone and usually at depths of more than 200 m. This location accounts for their delayed discovery, for they are obtained only by dredging. They are sessile animals that secrete very long chitinous tubes in which they live, probably extending the anterior end of the body only for absorbing nutrients. The tubes are generally oriented upright in the bottom ooze. The tube is usually about the same length as the animal, which can move up or down inside the tube but cannot turn around.

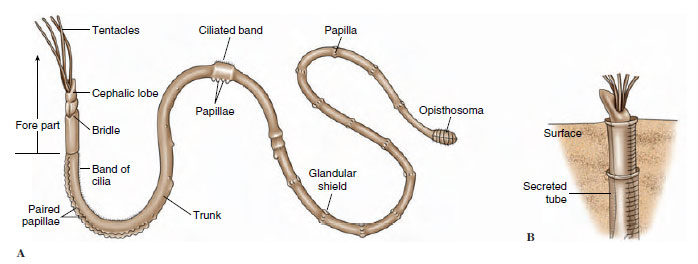

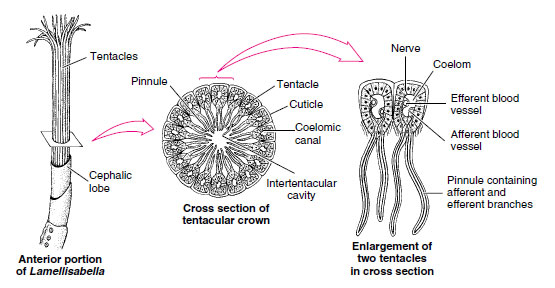

Beardworms have a long, cylindrical body covered with cuticle. The body is divided into a short anterior forepart; a long, very slender trunk; and a small, segmented opisthosoma (Figure 21-7). At its anterior, the cephalic lobe bears from 1 to 260 long tentacles (the “beard” that gives the phylum its name), depending on species. Tentacles are hollow extensions of the coelom and bear minute pinnules. For a part or all of their length, the tentacles lie parallel with each other, enclosing a cylindrical intertentacular space into which the pinnules project (Figure 21-8).

|

| Figure 21-7 Diagram of a typical pogonophoran. A, External features. In life, the body is much more elongated than shown in this diagram. B, Position in tube. |

|

| Figure 21-8 Cross section of tentacular crown of pogonophore Lamellisabella. Tentacles arise from ventral side of forepart at base of cephalic lobe. Tentacles (which vary in number in different species) enclose a cylindrical space, with the pinnules forming a kind of food-catching network. Food molecules may be absorbed into the blood supply of tentacles and pinnules. |

The long trunk bears papillae and, about midway back, two rings of shorttoothed setae called girdles, which grip the tube wall, allowing the two halves of the body to contract or extend independently in the tube. Posterior to the girdles, the trunk is very thin and easily broken when the animals are collected. In fact, the segmented tail end of the animal, or opisthosoma, was not found and described until after 1963! It is thicker than the trunk and has 5 to 23 short segments that bear setae.

Cuticle, epidermis, and circular and longitudinal muscles compose the body wall. The cuticle is similar in structure to that of annelids and sipunculans.

Pogonophores are remarkable in having no mouth or digestive tract, making their mode of nutrition a puzzling matter. They absorb some nutrients dissolved in seawater, such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids, through the pinnules and microvilli of their tentacles. Most of their energy, however, apparently is derived from a mutualistic association with chemoautotrophic bacteria. These bacteria oxidize hydrogen sulfide to provide energy to produce organic compounds from carbon dioxide. Pogonophores bear the bacteria in an organ called the trophosome, which is derived embryonically from the midgut (all traces of the foregut and hindgut are absent in adults).

Sexes are separate, with a pair of gonads and a pair of gonoducts in the trunk section. Cleavage is unequal and atypical. It seems to be closer to radial than to spiral. Development of the apparent coelom is schizocoelic, not enterocoelic as was originally described. The worm-shaped embryo is ciliated but a poor swimmer. It is probably swept along by water currents until it settles.

Because the first specimens of Pogonophora that were dredged up lacked the segmented opisthosoma, Ivanov and other early workers, who believed they were working with whole specimens, described the coelom as trimeric (composed of three parts), like that of the hemichordates, and assumed that the organisms were deuterostomes. Ivanov also described the larval coelom as being trimeric. The later discovery of the segmented posterior end caused some revision of the hypothesis. The adult coelom has proved to be polymeric, not trimeric. That fact and schizocoelic development of larvae point toward an affinity with protostomes rather than deuterostomes. Pogonophore tubes were originally thought to resemble those of hemichordate pterobranchs, but analysis of their amino acid and chitin content shows no relationship to pterobranchs. Pogonophores have photoreceptor cells very similar to those of annelids (oligochaetes and leeches), and structure of the cuticle, makeup of the setae, and segmentation of the opisthosoma all strongly suggest a relationship with the annelids. However, the phylogenetic position of the Pogonophora must be considered still unsettled until the embryology of more species of more than one family is studied.

Adaptive radiation has not been extensive. The chief areas of diversity are in the structure of the tentacular crown and the tube.