Phylum Tardigrada

Phylum Tardigrada

Tardigrada (tar-di-gray´da) (L. tardus, slow, + gradus, step), or “water bears,” are minute organisms usually less than a millimeter in length. Most of the 300 to 400 species are terrestrial forms that live in the water film surrounding mosses and lichens. Some live in freshwater algae or mosses or in bottom debris, and a few are marine, inhabiting interstitial spaces between sand grains, in both deep and shallow seawater. They share many characteristics with arthropods.

They have an elongated, cylindrical, or a long oval body that is unsegmented. The head is merely the anterior part of the trunk. The trunk bears four pairs of short, stubby, unjointed legs, each armed with four to eight claws (Figure 21-13). The body is covered by a nonchitinous cuticle that is molted along with the claws and buccal apparatus four or more times in the life history. Cilia are absent. Common American genera are Macrobiotus (Gr. makros, large, + biotos, life), Echiniscus (Gr. echinos, hedgehog, + iskos, dim. suffix), and Hypsibius (Gr. hypsos, high, height, + bios, life).

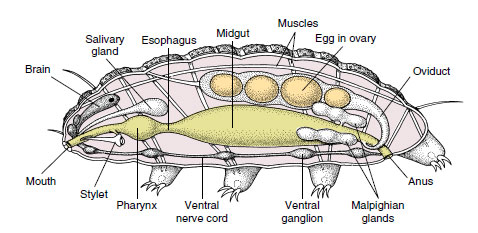

The mouth opens into a buccal tube that empties into a muscular pharynx that is adapted for sucking (Figure 21-14). Two needlelike stylets flanking the buccal tube can be protruded through the mouth. The stylets pierce the cellulose walls of plant cells, and the pharynx sucks in the liquid contents. Some tardigrades suck body juices of nematodes, rotifers, and other small animals. Some, such as Echiniscus, expel feces when molting, leaving the feces in the discarded cuticle. At the junction of stomach and rectum, three glands, thought to be excretory and often called malpighian tubules, empty into the digestive system.

Most of the body cavity is a hemocoel, with the true coelom restricted to the gonadal cavity. There are no circulatory or respiratory systems, gaseous exchange occurring through the body surface.

The muscular system consists of a number of long muscle bands. Circular muscles are absent, but hydrostatic pressure of the body fluid may act as a skeleton. Being unable to swim, water bears creep about with apparent awkwardness, clinging to the substrate with their claws.

The brain is relatively large and covers most of the dorsal surface of the pharynx. Circumpharyngeal connectives link it to the subpharyngeal ganglion, from which the double ventral nerve cord extends posteriorly as a chain of four ganglia.

Sexes are separate in tardigrades. In some freshwater and moss-dwelling species, males are unknown and parthenogenesis seems to be the rule. In marine species, however, males and females occur with approximately equal frequency. Eggs of some species are highly ornate (Figure 21-15). Egg laying, like defecation, apparently occurs only at molting, when the volume of coelomic fluid is reduced. Females of some species deposit eggs in the molted cuticle (Figure 21-16). Males gather around the old cuticle and shed sperm into it. Fertilization in other species is internal but only at the time of molting.

Cleavage is holoblastic but atypical, and a stereogastrula is formed. Six pairs of coelomic pouches arise from the gut, but all except the last pair disaggregate to form the buccal apparatus, pharynx, and body musculature. The last pair fuses to form the gonad. Thus the gonocoel (which is enterocoelic) is the only true coelom left in adults. Development is direct.

One of the most intriguing features of terrestrial tardigrades is their capacity to enter a state of suspended animation, called cryptobiosis, during which metabolism is virtually imperceptible; the organism can withstand harsh environmental conditions. Under gradual drying conditions, the water content of the body decreases from 85% to only 3%, movement ceases, and the body becomes barrel shaped. In a cryptobiotic state tardigrades can resist temperature extremes, ionizing radiation, oxygen deficiency, and other adverse conditions and may survive for years. Activity resumes when moisture is again available.

Tardigrada (tar-di-gray´da) (L. tardus, slow, + gradus, step), or “water bears,” are minute organisms usually less than a millimeter in length. Most of the 300 to 400 species are terrestrial forms that live in the water film surrounding mosses and lichens. Some live in freshwater algae or mosses or in bottom debris, and a few are marine, inhabiting interstitial spaces between sand grains, in both deep and shallow seawater. They share many characteristics with arthropods.

|

| Figure 21-13 Scanning electron micrograph of an aquatic tardigrade, Pseudobiotus. |

They have an elongated, cylindrical, or a long oval body that is unsegmented. The head is merely the anterior part of the trunk. The trunk bears four pairs of short, stubby, unjointed legs, each armed with four to eight claws (Figure 21-13). The body is covered by a nonchitinous cuticle that is molted along with the claws and buccal apparatus four or more times in the life history. Cilia are absent. Common American genera are Macrobiotus (Gr. makros, large, + biotos, life), Echiniscus (Gr. echinos, hedgehog, + iskos, dim. suffix), and Hypsibius (Gr. hypsos, high, height, + bios, life).

The mouth opens into a buccal tube that empties into a muscular pharynx that is adapted for sucking (Figure 21-14). Two needlelike stylets flanking the buccal tube can be protruded through the mouth. The stylets pierce the cellulose walls of plant cells, and the pharynx sucks in the liquid contents. Some tardigrades suck body juices of nematodes, rotifers, and other small animals. Some, such as Echiniscus, expel feces when molting, leaving the feces in the discarded cuticle. At the junction of stomach and rectum, three glands, thought to be excretory and often called malpighian tubules, empty into the digestive system.

|

| Figure 21-14 Internal anatomy of a tardigrade. |

Most of the body cavity is a hemocoel, with the true coelom restricted to the gonadal cavity. There are no circulatory or respiratory systems, gaseous exchange occurring through the body surface.

The muscular system consists of a number of long muscle bands. Circular muscles are absent, but hydrostatic pressure of the body fluid may act as a skeleton. Being unable to swim, water bears creep about with apparent awkwardness, clinging to the substrate with their claws.

The brain is relatively large and covers most of the dorsal surface of the pharynx. Circumpharyngeal connectives link it to the subpharyngeal ganglion, from which the double ventral nerve cord extends posteriorly as a chain of four ganglia.

|

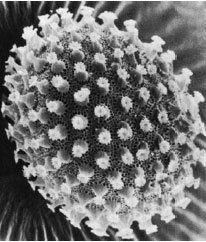

| Figure 21-15 Scanning electron micrograph of the highly ornate egg of the tardigrade, Macrobiotus hufelandii. |

Sexes are separate in tardigrades. In some freshwater and moss-dwelling species, males are unknown and parthenogenesis seems to be the rule. In marine species, however, males and females occur with approximately equal frequency. Eggs of some species are highly ornate (Figure 21-15). Egg laying, like defecation, apparently occurs only at molting, when the volume of coelomic fluid is reduced. Females of some species deposit eggs in the molted cuticle (Figure 21-16). Males gather around the old cuticle and shed sperm into it. Fertilization in other species is internal but only at the time of molting.

Cleavage is holoblastic but atypical, and a stereogastrula is formed. Six pairs of coelomic pouches arise from the gut, but all except the last pair disaggregate to form the buccal apparatus, pharynx, and body musculature. The last pair fuses to form the gonad. Thus the gonocoel (which is enterocoelic) is the only true coelom left in adults. Development is direct.

One of the most intriguing features of terrestrial tardigrades is their capacity to enter a state of suspended animation, called cryptobiosis, during which metabolism is virtually imperceptible; the organism can withstand harsh environmental conditions. Under gradual drying conditions, the water content of the body decreases from 85% to only 3%, movement ceases, and the body becomes barrel shaped. In a cryptobiotic state tardigrades can resist temperature extremes, ionizing radiation, oxygen deficiency, and other adverse conditions and may survive for years. Activity resumes when moisture is again available.

|

| Figure 21-16 Molted cuticle of a tardigrade, containing a number of fertilized eggs. |