Genetic imprinting

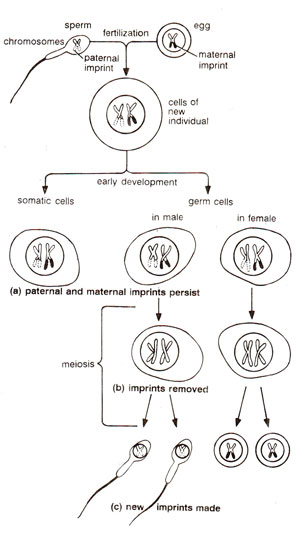

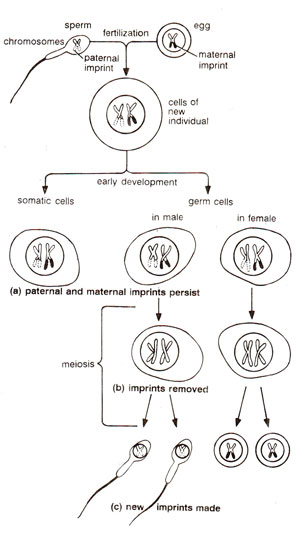

Fig. 17.24. Genetic imprinting of chromosomes, so that they are identifiable as having been donated to an individual (a) by its father (dotted screen) or (b) by its mother (solid black). This imprinting may persist for many cell generations, but disappears in germ cells during meiosis.

Any epigenetic changes in the germ cells, such as the inactivation of an X-chromosome, are reversed or altered during or just before meiosis, which leads to the production of sperms and eggs. After this reversal of epigenetic changes, the eggs and sperms are differentially imprinted. As a consequence of this, even if a chromosome in a sperm happens to have been inherited from the fathers’ mother, it would still bear the male imprint (Fig. 17.24). Such imprinting has been found to be crucial to normal development in mice and other mammals, because it silences and activates different sets of genes in the maternal and paternal chromosomes. These differences in paternal and maternal chromosomes complement each other in directing normal development. This differentiation or reprogramming of the genome is believed to be achieved through changes in methylation patterns. In mice, differential methylation of paternal and maternal chromosomes has actually been demonstrated.

Fig. 17.24. Genetic imprinting of chromosomes, so that they are identifiable as having been donated to an individual (a) by its father (dotted screen) or (b) by its mother (solid black). This imprinting may persist for many cell generations, but disappears in germ cells during meiosis.