Advantages of Sociality

Living together may be beneficial in many ways. One obvious benefit for social aggregations is defense, both passive and active, from predators. Musk-oxen that form a passive defensive circle when threatened by a wolf pack are much less vulnerable than an individual facing the wolves alone.

As an example of active defense, a breeding colony of gulls, alerted by the alarm calls of a few, attack predators en masse; this collective attack is certain to discourage a predator more effectively than individual attacks. Members of a town of prairie dogs, although divided into social units called coteries, cooperate by warning each other with a special bark when danger threatens. Thus every individual in a social organization benefits from the eyes, ears, and noses of all other members of the group. Experimental tests using a wide variety of predators and prey support the notion that the more animals there are in a group, the less likely an individual within the group will be eaten.

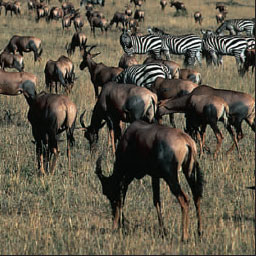

Sociality offers several benefits to animals reproduction. It facilitates encounters between males and females, which, for solitary animals, may consume much time and energy. Sociality also helps synchronize reproductive behavior through the mutual stimulation that individuals have on one another. Among colonial birds the sounds and displays of courting individuals set in motion prereproductive endocrine changes in other individuals. Because there is more social stimulation, large colonies of gulls produce more young per nest than do small colonies. Furthermore, parental care that social animals provide their offspring increases survival of the brood (Figure 38-12). Social living provides opportunities for individuals to give aid and to share food with young other than their own. Such interactions within a social network have produced some intricate cooperative behavior among parents, their young, and their kin.

Of the many other advantages of social organization noted by behaviorists, we will mention only a few in this brief treatment: cooperation in hunting for food; huddling for mutual protection from severe weather; opportunities for division of labor, which is especially well developed in the social insects with their caste systems; and the potential for learning and transmitting useful information through the society.

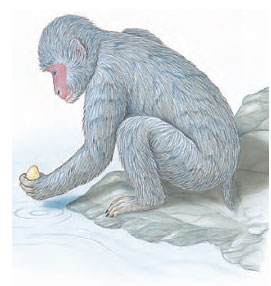

Observers of a seminatural colony of macaque monkeys in Japan recount an interesting example of acquiring and passing tradition in a society. The macaques were provisioned with sweet potatoes and wheat at a feeding station on the beach of an island colony. One day a young female named Imo was observed washing the sand off a sweet potato in seawater. The behavior was quickly imitated by Imo’s playmates and later by Imo’s mother. Still later when the young members of the troop became mothers they waded into the sea to wash their potatoes; their offspring imitated them without hesitation. The tradition was firmly established in the troop (Figure 38-13).

Some years later, Imo, an adult, discovered that she could separate wheat from sand by tossing a handfulof sandy wheat in the water; allowing the sand to sink, she could scoop up the floating wheat to eat. Again, within a few years, wheat-sifting became a tradition in the troop.

Imo’s peers and social inferiors copied her innovations most readily. The adult males, her superiors in the social hierarchy, would not adopt the practice but continued laboriously to pick wet sand grains off their sweet potatoes and scout the beach for single grains of wheat.

Social living also has some disadvantages as compared with a solitary existence for some animals. Species that survive by camouflage from potential predators profit by being dispersed. Large predators benefit from a solitary existence for a different reason, their requirement for a large supply of prey. Thus there is no overriding adaptive advantage to sociality that inevitably selects against the solitary way of life. It depends on the ecological situation.

As an example of active defense, a breeding colony of gulls, alerted by the alarm calls of a few, attack predators en masse; this collective attack is certain to discourage a predator more effectively than individual attacks. Members of a town of prairie dogs, although divided into social units called coteries, cooperate by warning each other with a special bark when danger threatens. Thus every individual in a social organization benefits from the eyes, ears, and noses of all other members of the group. Experimental tests using a wide variety of predators and prey support the notion that the more animals there are in a group, the less likely an individual within the group will be eaten.

Sociality offers several benefits to animals reproduction. It facilitates encounters between males and females, which, for solitary animals, may consume much time and energy. Sociality also helps synchronize reproductive behavior through the mutual stimulation that individuals have on one another. Among colonial birds the sounds and displays of courting individuals set in motion prereproductive endocrine changes in other individuals. Because there is more social stimulation, large colonies of gulls produce more young per nest than do small colonies. Furthermore, parental care that social animals provide their offspring increases survival of the brood (Figure 38-12). Social living provides opportunities for individuals to give aid and to share food with young other than their own. Such interactions within a social network have produced some intricate cooperative behavior among parents, their young, and their kin.

Of the many other advantages of social organization noted by behaviorists, we will mention only a few in this brief treatment: cooperation in hunting for food; huddling for mutual protection from severe weather; opportunities for division of labor, which is especially well developed in the social insects with their caste systems; and the potential for learning and transmitting useful information through the society.

Observers of a seminatural colony of macaque monkeys in Japan recount an interesting example of acquiring and passing tradition in a society. The macaques were provisioned with sweet potatoes and wheat at a feeding station on the beach of an island colony. One day a young female named Imo was observed washing the sand off a sweet potato in seawater. The behavior was quickly imitated by Imo’s playmates and later by Imo’s mother. Still later when the young members of the troop became mothers they waded into the sea to wash their potatoes; their offspring imitated them without hesitation. The tradition was firmly established in the troop (Figure 38-13).

Some years later, Imo, an adult, discovered that she could separate wheat from sand by tossing a handfulof sandy wheat in the water; allowing the sand to sink, she could scoop up the floating wheat to eat. Again, within a few years, wheat-sifting became a tradition in the troop.

Imo’s peers and social inferiors copied her innovations most readily. The adult males, her superiors in the social hierarchy, would not adopt the practice but continued laboriously to pick wet sand grains off their sweet potatoes and scout the beach for single grains of wheat.

Social living also has some disadvantages as compared with a solitary existence for some animals. Species that survive by camouflage from potential predators profit by being dispersed. Large predators benefit from a solitary existence for a different reason, their requirement for a large supply of prey. Thus there is no overriding adaptive advantage to sociality that inevitably selects against the solitary way of life. It depends on the ecological situation.