Describing Behavior: Principles of Classical Ethology

Describing

Behavior: Principles

of Classical Ethology

Early behaviorists, through step-bystep analysis of the behavior of animals in nature, focused on the relatively invariant components of behavior. From such studies emerged several concepts that were first popularized in Tinbergen’s influential book. The Study of Instinct (1951).

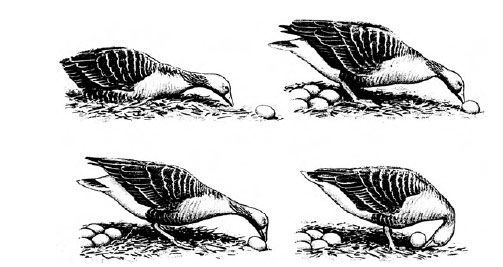

Some basic concepts of animal behavior can be illustrated by considering the egg-retrieval response of the greylag goose (Figure 38-2), described by Lorenz and Tinbergen in a famous paper published in 1938. If Lorenz and Tinbergen presented a female greylag goose with an egg a short distance from her nest, she would rise, extend her neck until the bill was just over the egg and then bend her neck, pulling the egg carefully into the nest.

Although this behavior appeared to be intelligent, Tinbergen and Lorenz noticed that if they removed the egg once the goose had begun her retrieval, or if the egg being retrieved slipped away and rolled down the outer slope of the nest, the goose would continue the retrieval movement without the egg until she was again settled comfortably on her nest. Then, seeing that the egg had not been retrieved, she would begin the eggrolling pattern all over again. Thus the bird performed eggrolling behavior as if it were a program that, once initiated, had to run to completion. Lorenz and Tinbergen viewed egg-retrieval as a “fixed” pattern of behavior: a motor pattern that is mostly invariable in its performance. A behavior of this type, carried out in an orderly, predictable sequence is often called stereotypical behavior. Of course, stereotyped behavior may not be performed identically on all occasions. But it should be recognizable, even when performed inappropriately. Further experiments by Tinbergen disclosed that the greylag goose was not particularly discriminating about what she retrieved. Almost any smooth and rounded object placed outside the nest would trigger the egg-rolling behavior; even a small toy dog and a large yellow balloon were dutifully retrieved. But once the goose settled down on such objects, they obviously did not feel right and she discarded them.

Lorenz and Tinbergen realized that presence of an egg outside the nest must act as a stimulus, or trigger, that released egg-retrieval behavior. Lorenz termed the triggering stimulus a releaser; a simple feature in the environment that would trigger a certain innate behavior. Or, because the animal usually responded to some specific aspect of the releaser (sound, shape, or color, for example) the effective stimulus was called a sign stimulus. Behaviorists have described hundreds of examples of sign stimuli. In every case the response is highly predictable. For example, the alarm call of adult herring gulls always releases a crouching freezeresponse in their chicks. Or, to cite an example given in an earlier section , certain nocturnal moths take evasive maneuvers or drop to the ground when they hear the ultrasonic cries of bats that feed on them; most other sounds do not release this response.

These examples illustrate the predictable

and programmed nature of

much animal behavior. This is even

more evident when stereotyped behavior

is released inappropriately. In the

spring the male three-spined stickleback,

a small fish, selects a territory

that it defends vigorously against other

males. The underside of the male

becomes bright red, and the approach

of another red-bellied male will release

a threat posture or even an aggressive

attack. Tinbergen’s suspicion that the

red belly of the male served as a

releaser for aggression was reinforced

when a passing red postal truck

evoked attack behavior from the males

in his aquarium. Tinbergen then carried

out experiments using a series of

models, which he presented to the

males. He found that they vigorously

attacked any model bearing a red

stripe, even a plump lump of wax with

a red underside. Yet a carefully made

model that closely resembled a male

stickleback but lacked the red belly

was ignored (Figure 38-3). Tinbergen

discovered other examples of stereotyped

behavior released by simple sign

stimuli. Male English robins furiously

attacked a bundle of red feathers

placed in their territory but ignored a

stuffed juvenile robin without the red

feathers (Figure 38-4).

We have seen in the examples above that there are costs to programmed behavior because it may lead to improper responses. Fortunately for red-bellied sticklebacks and red-breasted English robins, their aggressive response toward red works appropriately most of the time because red objects are uncommon in the worlds of these animals. But why don’t these and other animals simply use reasoning to choose the correct response rather than relying mostly on automatic responses? Under conditions that are relatively consistent and predictable, automatic preprogrammed responses may be most efficient. Even if they can or could, thinking about or learning the correct response may take too much time. Releasers have the advantage of focusing the animal’s attention on the relevant signal, and the release of a preprogrammed stereotyped behavior will enable an animal to respond rapidly when speed may be essential for survival.

Early behaviorists, through step-bystep analysis of the behavior of animals in nature, focused on the relatively invariant components of behavior. From such studies emerged several concepts that were first popularized in Tinbergen’s influential book. The Study of Instinct (1951).

|

| Figure 38-2 Egg-rolling behavior of the greylag goose (Anser anser) |

Some basic concepts of animal behavior can be illustrated by considering the egg-retrieval response of the greylag goose (Figure 38-2), described by Lorenz and Tinbergen in a famous paper published in 1938. If Lorenz and Tinbergen presented a female greylag goose with an egg a short distance from her nest, she would rise, extend her neck until the bill was just over the egg and then bend her neck, pulling the egg carefully into the nest.

Although this behavior appeared to be intelligent, Tinbergen and Lorenz noticed that if they removed the egg once the goose had begun her retrieval, or if the egg being retrieved slipped away and rolled down the outer slope of the nest, the goose would continue the retrieval movement without the egg until she was again settled comfortably on her nest. Then, seeing that the egg had not been retrieved, she would begin the eggrolling pattern all over again. Thus the bird performed eggrolling behavior as if it were a program that, once initiated, had to run to completion. Lorenz and Tinbergen viewed egg-retrieval as a “fixed” pattern of behavior: a motor pattern that is mostly invariable in its performance. A behavior of this type, carried out in an orderly, predictable sequence is often called stereotypical behavior. Of course, stereotyped behavior may not be performed identically on all occasions. But it should be recognizable, even when performed inappropriately. Further experiments by Tinbergen disclosed that the greylag goose was not particularly discriminating about what she retrieved. Almost any smooth and rounded object placed outside the nest would trigger the egg-rolling behavior; even a small toy dog and a large yellow balloon were dutifully retrieved. But once the goose settled down on such objects, they obviously did not feel right and she discarded them.

Lorenz and Tinbergen realized that presence of an egg outside the nest must act as a stimulus, or trigger, that released egg-retrieval behavior. Lorenz termed the triggering stimulus a releaser; a simple feature in the environment that would trigger a certain innate behavior. Or, because the animal usually responded to some specific aspect of the releaser (sound, shape, or color, for example) the effective stimulus was called a sign stimulus. Behaviorists have described hundreds of examples of sign stimuli. In every case the response is highly predictable. For example, the alarm call of adult herring gulls always releases a crouching freezeresponse in their chicks. Or, to cite an example given in an earlier section , certain nocturnal moths take evasive maneuvers or drop to the ground when they hear the ultrasonic cries of bats that feed on them; most other sounds do not release this response.

|

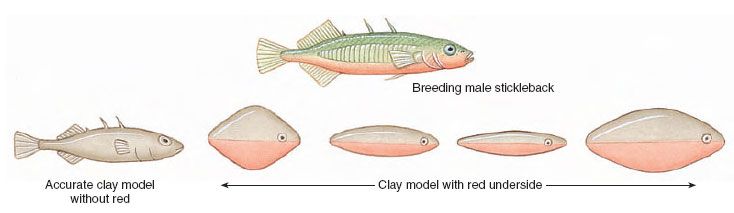

| Figure 38-3 Stickleback models used to study territorial behavior. The carefully made model of a stickleback (left), without a red belly, is attacked much less frequently by a territorial male stickleback than the four simple red-bellied models. |

|

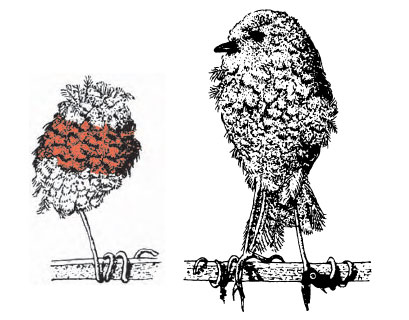

| Figure 38-4 Two models of an English robin. The bundle of red feathers is attacked by male robins, whereas the stuffed juvenile bird (right) without a red breast is ignored. |

We have seen in the examples above that there are costs to programmed behavior because it may lead to improper responses. Fortunately for red-bellied sticklebacks and red-breasted English robins, their aggressive response toward red works appropriately most of the time because red objects are uncommon in the worlds of these animals. But why don’t these and other animals simply use reasoning to choose the correct response rather than relying mostly on automatic responses? Under conditions that are relatively consistent and predictable, automatic preprogrammed responses may be most efficient. Even if they can or could, thinking about or learning the correct response may take too much time. Releasers have the advantage of focusing the animal’s attention on the relevant signal, and the release of a preprogrammed stereotyped behavior will enable an animal to respond rapidly when speed may be essential for survival.