Aggression and Dominance

Many animal species are social because of the numerous benefits that sociality offers. Sociality requires cooperation. At the same time animals, like governments, tend to look out for their own interests. In short, they are in competition with one another because of limitations in the common resources that all require for life. Animals may compete for food, water, sexual mates, or shelter when such requirements are limited in quantity and are therefore worth a fight.

Much of what animals do to resolve competition is called aggression, which we may define as an offensive physical action, or threat, to force others to abandon something they own or might attain. Many behaviorists consider aggression part of a somewhat more inclusive interaction called agonistic (Gr. contest) behavior, referring to any activity related to fighting, whether it be aggression, defense, submission, or retreat.

Contrary to the widely held notion that aggressive behavior aims at the destruction or at least defeat of an opponent, most aggressive encounters are duels that lack the violence that we usually associate with fighting. Many species possess specialized weapons such as sharpened teeth, beaks, claws, or horns that are used for protection from, or predation on, other species. Although potentially dangerous, such weapons are seldom used in any severely damaging way against members of their own species.

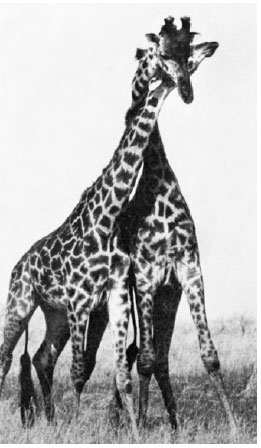

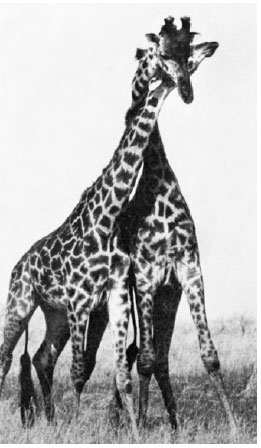

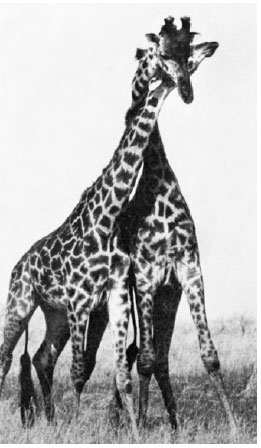

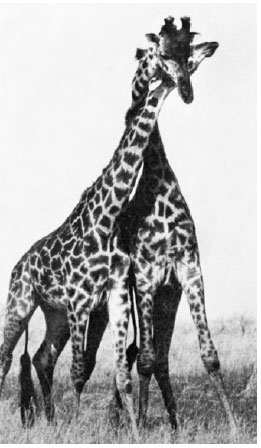

Animal aggression within the species seldom results in injury or death because animals have evolved many symbolic ritualized displays that carry mutually understood meanings. A ritualized display is a behavior that has been modified through evolution to make it increasingly effective in serving a communicative function. Through ritualization, simple movements or traits become more intensive, conspicuous, or precise, and acquire the function of a signal. The result of such intensification is to reduce the possibility of misunderstanding. Fights over mates, food, or territory become ritualized jousts rather than bloody, no-holds-barred battles. When fiddler crabs spar for territory, their large claws usually are only slightly opened, Even in intense fighting when the claws are used, the crabs grasp each other in a way that prevents reciprocal injury. Rival male poisonous snakes engage in stylized bouts by winding themselves together; each attempts to butt the other’s head with its own until one becomes so fatigued that it retreats. The rivals never bite each other. Many species of fish contest territorial boundaries with lateral displays, the males puffing themselves to look as threatening as possible. The encounter is usually settled when either animal perceives itself obviously inferior, folds up its fins, and swims away. Rival giraffes engage in largely symbolic “necking” matches in which two males standing side by side wrap and unwrap their necks around each other (Figure 38-14). Neither uses its potentially lethal hooves on the other, and neither is injured.

Animal aggression within the species seldom results in injury or death because animals have evolved many symbolic ritualized displays that carry mutually understood meanings. A ritualized display is a behavior that has been modified through evolution to make it increasingly effective in serving a communicative function. Through ritualization, simple movements or traits become more intensive, conspicuous, or precise, and acquire the function of a signal. The result of such intensification is to reduce the possibility of misunderstanding. Fights over mates, food, or territory become ritualized jousts rather than bloody, no-holds-barred battles. When fiddler crabs spar for territory, their large claws usually are only slightly opened, Even in intense fighting when the claws are used, the crabs grasp each other in a way that prevents reciprocal injury. Rival male poisonous snakes engage in stylized bouts by winding themselves together; each attempts to butt the other’s head with its own until one becomes so fatigued that it retreats. The rivals never bite each other. Many species of fish contest territorial boundaries with lateral displays, the males puffing themselves to look as threatening as possible. The encounter is usually settled when either animal perceives itself obviously inferior, folds up its fins, and swims away. Rival giraffes engage in largely symbolic “necking” matches in which two males standing side by side wrap and unwrap their necks around each other (Figure 38-14). Neither uses its potentially lethal hooves on the other, and neither is injured.

Thus animals fight as though programmed by rules that prevent serious injury. Fights between rival bighorn rams are spectacular to watch, and the sound of clashing horns may be heard for hundreds of meters (Figure 38-15). But the skull is so well protected by the massive horns that injury occurs only by accident. Nevertheless, despite these constraints, aggressive encounters on occasion can be true fights to the death. If African male elephants are unable to resolve dominance conflicts painlessly with ritual postures, they may resort to incredibly violent battles, with each trying to plunge its tusks into the most vulnerable parts of the opponent’s body.

Thus animals fight as though programmed by rules that prevent serious injury. Fights between rival bighorn rams are spectacular to watch, and the sound of clashing horns may be heard for hundreds of meters (Figure 38-15). But the skull is so well protected by the massive horns that injury occurs only by accident. Nevertheless, despite these constraints, aggressive encounters on occasion can be true fights to the death. If African male elephants are unable to resolve dominance conflicts painlessly with ritual postures, they may resort to incredibly violent battles, with each trying to plunge its tusks into the most vulnerable parts of the opponent’s body.

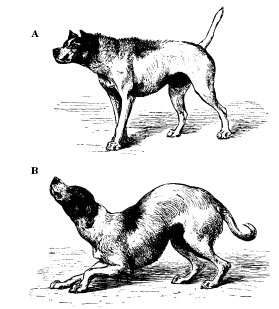

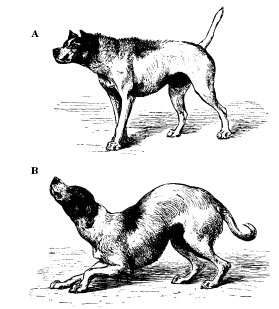

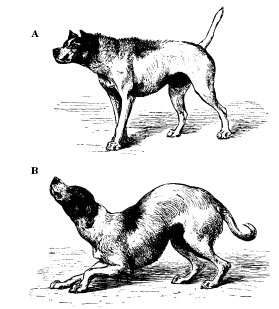

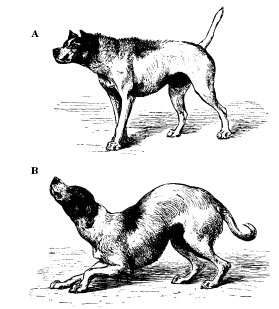

More commonly, however, the loser of a ritualized encounter may simply run away, or signal defeat by a specialized subordination ritual. If it becomes evident to him that he is going to lose anyway, he profits by communicating his submission as quickly as possible, thereby avoiding the cost of a real thrashing. Such submissive displays that signal the end of a fight may be almost the opposite of threat displays (Figure 38-16). In his book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Charles Darwin described the seemingly opposite nature of threat and appeasement displays as the “principle of antithesis.” The principle remains accepted by animal behaviorists today.

More commonly, however, the loser of a ritualized encounter may simply run away, or signal defeat by a specialized subordination ritual. If it becomes evident to him that he is going to lose anyway, he profits by communicating his submission as quickly as possible, thereby avoiding the cost of a real thrashing. Such submissive displays that signal the end of a fight may be almost the opposite of threat displays (Figure 38-16). In his book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Charles Darwin described the seemingly opposite nature of threat and appeasement displays as the “principle of antithesis.” The principle remains accepted by animal behaviorists today.

The winner of an aggressive competition is dominant to the loser, the subordinate. For the victor, dominance means enhanced access to all contested resources that contribute to reproductive success: food, mates, and territory. In a social species, dominance interactions often take the form of a dominance hierarchy. One animal at the top wins encounters with all other members in the social group; the second in rank wins all but those with the top-ranking individual.

Such a simple, ordered hierarchy was first observed in chickens by Schjelderup-Ebbe, who called the hierarchy a “peck-order.” Once social ranking is established, actual pecking diminishes and is replaced by threats, bluffs, and bows. Top hens and cocks get unquestioned access to feed and water, dusting areas, and the roost. The system works because it reduces social tensions that would constantly surface if animals had to fight all the time over social position. However, not all dominance hierarchies have clear-cut dominant and subordinate individuals. In some hierarchies, dominant animals are frequently challenged by subordinates. The subordinates in any social order may be expendable. In many systems they never get a chance to reproduce, and when times get difficult they are often the first to die. During times of food scarcity, death of weaker members helps to protect the resource for stronger members. Rather than sharing food, the excess population is sacrificed. This sacrifice is not viewed by contemporary behaviorists as resulting from some direct, purposeful process ensuring “good for the species”; it is a consequence of the individual advantage that the stronger, dominant individuals possess during such circumstances.

Much of what animals do to resolve competition is called aggression, which we may define as an offensive physical action, or threat, to force others to abandon something they own or might attain. Many behaviorists consider aggression part of a somewhat more inclusive interaction called agonistic (Gr. contest) behavior, referring to any activity related to fighting, whether it be aggression, defense, submission, or retreat.

Contrary to the widely held notion that aggressive behavior aims at the destruction or at least defeat of an opponent, most aggressive encounters are duels that lack the violence that we usually associate with fighting. Many species possess specialized weapons such as sharpened teeth, beaks, claws, or horns that are used for protection from, or predation on, other species. Although potentially dangerous, such weapons are seldom used in any severely damaging way against members of their own species.

Figure 38-14 Male Masai giraffes. Giraffa camelopardalis, fight for social dominance. Such fights are largely symbolic, seldom resulting in injury.

Figure 38-14 Male Masai giraffes. Giraffa camelopardalis, fight for social dominance. Such fights are largely symbolic, seldom resulting in injury.

Figure 38-15 Male bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis, fight for social dominance during the breeding season.

Figure 38-15 Male bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis, fight for social dominance during the breeding season.

Figure 38-16 Darwin's principle of antithesis as exemplified by the postures of dogs. A) A dog approaches another dog with hostile, aggressive intentions. B) The same dog is in a humble and conciliatory state of mind. The signals of aggressive display have been reversed.

Figure 38-16 Darwin's principle of antithesis as exemplified by the postures of dogs. A) A dog approaches another dog with hostile, aggressive intentions. B) The same dog is in a humble and conciliatory state of mind. The signals of aggressive display have been reversed.

The winner of an aggressive competition is dominant to the loser, the subordinate. For the victor, dominance means enhanced access to all contested resources that contribute to reproductive success: food, mates, and territory. In a social species, dominance interactions often take the form of a dominance hierarchy. One animal at the top wins encounters with all other members in the social group; the second in rank wins all but those with the top-ranking individual.

Such a simple, ordered hierarchy was first observed in chickens by Schjelderup-Ebbe, who called the hierarchy a “peck-order.” Once social ranking is established, actual pecking diminishes and is replaced by threats, bluffs, and bows. Top hens and cocks get unquestioned access to feed and water, dusting areas, and the roost. The system works because it reduces social tensions that would constantly surface if animals had to fight all the time over social position. However, not all dominance hierarchies have clear-cut dominant and subordinate individuals. In some hierarchies, dominant animals are frequently challenged by subordinates. The subordinates in any social order may be expendable. In many systems they never get a chance to reproduce, and when times get difficult they are often the first to die. During times of food scarcity, death of weaker members helps to protect the resource for stronger members. Rather than sharing food, the excess population is sacrificed. This sacrifice is not viewed by contemporary behaviorists as resulting from some direct, purposeful process ensuring “good for the species”; it is a consequence of the individual advantage that the stronger, dominant individuals possess during such circumstances.