Bird Populations

Bird Populations

Bird populations, like those of other animal groups, vary in size from year to year. Snowy owls, for example, are subject to population cycles that closely follow cycles in their food supply, mainly rodents. Voles, mice, and lemmings in the north have a fairly regular 4-year cycle of abundance; at population peaks, predator populations of foxes, weasels, and buzzards, as well as snowy owls, increase because there is abundant food for rearing their young. After a crash in the rodent population, snowy owls move south, seeking alternative food supplies. They occasionally appear in large numbers in southern Canada and the northern United States, where their total absence of fear of humans makes them easy targets for thoughtless hunters.

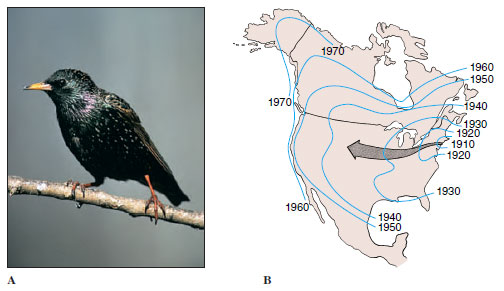

Occasionally the activities of people bring about spectacular changes in bird distribution. Both starlings (Figure 29-29) and house sparrows have been accidentally or deliberately introduced into numerous countries, to become the two most abundant bird species on earth, with the exception of domestic fowl.

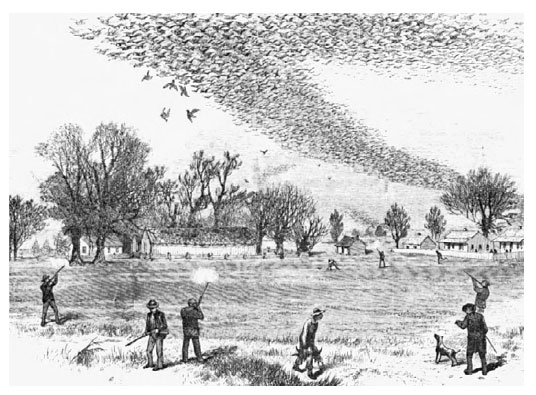

Humans also are responsible for the extinction of many bird species. More than 80 species of birds have, since 1695, followed the last dodo to extinction. Many were victims of changes in their habitat or competition with better-adapted species. But several have been hunted to extinction, among them the passenger pigeon, which only a century ago darkened the skies over North America in incredible numbers estimated in the billions (Figure 29-30).

Today, game bird hunting is a well-managed renewable resource in the United States and Canada, and while hunters kill millions of game birds each year, none of the 74 bird species legally hunted is endangered. Hunting interests, by acquiring large areas of wetlands for migratory bird refuges and sanctuaries, have contributed to the recovery of both game and nongame birds.

Of particular concern is the recent sharp decline of songbirds in the United States and southern Canada. Amateur birdwatchers and ornithologists have recorded that many songbird species that were abundant as recently as 40 years ago are now suddenly scarce. There are several reasons for the decline. Intensification of agriculture, permitted by the use of herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers, has deprived groundnesting birds of fields that were left fallow before the use of these agents. The excessive fragmentation of forests throughout much of the United States has increased exposure of nests of forest-dwelling species to nest predators such as blue jays, raccoons, and opossums, and to nest parasites such as the brown-headed cowbird. House cats also kill millions of small birds every year. From a study of radio-collared farm cats in Wisconsin, researchers estimated that in that state alone, cats may kill 19 million songbirds in a single year.

The rapid loss of tropical forests— approximately 170,000 square kilometers each year, an area about the size of the state of Washington—is depriving some 250 species of songbird migrants of their wintering homes. Recent studies indicate that stressors on the wintering grounds are seriously decreasing the physiological condition of birds, particularly songbirds, prior to northward migration. Of all the long-term threats facing songbird populations, tropical deforestation is the most serious and most intractable to change. If the rate of deforestation accelerates in the next few decades as expected, the world’s tropical forests will have disappeared by 2040 (Terborgh, 1992).

Some birds, such as robins, house sparrows, and starlings, can accommodate to these changes, and may even thrive on them. But for most the changes are adverse. Terborgh (1992) warns that unless we take leadership in managing our natural resources wisely we soon could be facing the silent spring that Rachel Carson envisioned in 1962.

Bird populations, like those of other animal groups, vary in size from year to year. Snowy owls, for example, are subject to population cycles that closely follow cycles in their food supply, mainly rodents. Voles, mice, and lemmings in the north have a fairly regular 4-year cycle of abundance; at population peaks, predator populations of foxes, weasels, and buzzards, as well as snowy owls, increase because there is abundant food for rearing their young. After a crash in the rodent population, snowy owls move south, seeking alternative food supplies. They occasionally appear in large numbers in southern Canada and the northern United States, where their total absence of fear of humans makes them easy targets for thoughtless hunters.

|

| Figure 29-29 A, Starling, Sturnus vulgaris. Starlings are omnivorous, eating mostly insects in spring and summer and shifting to wild fruits in the fall. B, Colonization of North America by starlings after the introduction of 120 birds into Central Park in New York City in 1890. There are now perhaps 100 million starlings in the United States alone, testimony to the great reproductive potential of birds. |

Occasionally the activities of people bring about spectacular changes in bird distribution. Both starlings (Figure 29-29) and house sparrows have been accidentally or deliberately introduced into numerous countries, to become the two most abundant bird species on earth, with the exception of domestic fowl.

Humans also are responsible for the extinction of many bird species. More than 80 species of birds have, since 1695, followed the last dodo to extinction. Many were victims of changes in their habitat or competition with better-adapted species. But several have been hunted to extinction, among them the passenger pigeon, which only a century ago darkened the skies over North America in incredible numbers estimated in the billions (Figure 29-30).

|

| Figure 29-30 Sport-shooting passenger pigeons in Louisiana during the nineteenth century. Relentless sport and market hunting, before the establishment of state and federal hunting regulations, eventually dropped the population too low to sustain colonial breeding. The last passenger pigeon died in captivity in 1914. |

Today, game bird hunting is a well-managed renewable resource in the United States and Canada, and while hunters kill millions of game birds each year, none of the 74 bird species legally hunted is endangered. Hunting interests, by acquiring large areas of wetlands for migratory bird refuges and sanctuaries, have contributed to the recovery of both game and nongame birds.

Of particular concern is the recent sharp decline of songbirds in the United States and southern Canada. Amateur birdwatchers and ornithologists have recorded that many songbird species that were abundant as recently as 40 years ago are now suddenly scarce. There are several reasons for the decline. Intensification of agriculture, permitted by the use of herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers, has deprived groundnesting birds of fields that were left fallow before the use of these agents. The excessive fragmentation of forests throughout much of the United States has increased exposure of nests of forest-dwelling species to nest predators such as blue jays, raccoons, and opossums, and to nest parasites such as the brown-headed cowbird. House cats also kill millions of small birds every year. From a study of radio-collared farm cats in Wisconsin, researchers estimated that in that state alone, cats may kill 19 million songbirds in a single year.

The rapid loss of tropical forests— approximately 170,000 square kilometers each year, an area about the size of the state of Washington—is depriving some 250 species of songbird migrants of their wintering homes. Recent studies indicate that stressors on the wintering grounds are seriously decreasing the physiological condition of birds, particularly songbirds, prior to northward migration. Of all the long-term threats facing songbird populations, tropical deforestation is the most serious and most intractable to change. If the rate of deforestation accelerates in the next few decades as expected, the world’s tropical forests will have disappeared by 2040 (Terborgh, 1992).

Some birds, such as robins, house sparrows, and starlings, can accommodate to these changes, and may even thrive on them. But for most the changes are adverse. Terborgh (1992) warns that unless we take leadership in managing our natural resources wisely we soon could be facing the silent spring that Rachel Carson envisioned in 1962.