Social Behavior and Reproduction

Social Behavior and

Reproduction

The adage says “birds of a feather flock together,” and many birds are indeed highly social creatures. Especially during the breeding season, sea birds gather, often in enormous colonies, to nest and rear young (Figure 29-22). Land birds, with some conspicuous exceptions, such as starlings and rooks, tend to be less gregarious than sea birds during breeding and to seek isolation for rearing their brood. But species that covet separation from their kind during breeding may aggregate for migration or feeding. Togetherness offers advantages: mutual protection from enemies, greater ease in finding mates, less opportunity for individual straying during migration, and mass huddling for protection against low night temperatures during migration. Certain species, such as pelicans (Figure 29-23), may use highly organized cooperative behavior to feed. At no time are the highly organized social interactions of birds more evident than during the breeding season, as they stake out territorial claims, select mates, build nests, incubate and hatch their eggs, and rear their young.

Reproductive System

During most of the year the testes of the male are tiny bean-shaped bodies. But during the breeding season they enlarge greatly, as much as 300 times larger than their nonbreeding size, afterward shrinking again to tiny bodies. Before discharge, the millions of sperm are stored in a seminal vesicle, which, like the testes, enlarges greatly during the breeding season. Since males of most species lack a penis, copulation is a matter of bringing cloacal surfaces into contact, usually while the male stands on the back of the female (Figure 29-24). Some swifts and hawks copulate in flight.

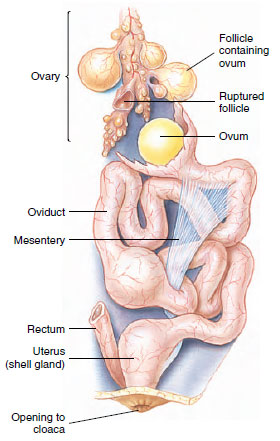

In the female of most birds, only the left ovary and oviduct develop; those on the right dwindle to vestigial structures. Eggs discharged from the ovary are picked up by the expanded end of the oviduct, the infundibulum (Figure 29-25 (below)). The oviduct runs posteriorly to the cloaca. While eggs are passing down the oviduct, albumin, or egg white, from special glands is added to them; farther down the oviduct, the shell membrane, shell, and shell pigments are also secreted about the egg. Fertilization takes place in the upper oviduct several hours before the layers of albumin, shell membranes, and shell are added. Sperm remain alive in the female oviduct for many days after a single mating. Hen eggs show good fertility for 5 or 6 days after mating, but then fertility drops rapidly. However, the occasional egg will be fertile as long as 30 days after separation of the hen from the rooster.

Mating Systems

The two most common types of mating systems in animals are monogamy, in which an individual mates with only one partner each breeding season, and polygamy, in which an individual mates with two or more partners each breeding period. Monogamy is rare in most animal groups, but in birds it is the general rule: more than 90% are monogamous. In a few bird species such as swans and geese, partners are chosen for life and often remain together throughout the year. Seasonal monogamy is more common, however; the great majority of migrant birds pair up during the breeding season but lead independent lives the rest of the year.

One reason that monogamy is much more common among birds than among mammals is that female birds are not equipped, as mammals are, with a built-in food supply for the young. Accordingly, the ability of the two sexes to provide parental care, especially food for the young, is more equal in birds than in mammals. A female bird will choose a male whose parental investment in their young is apt to be high and avoid a male that has mated with another female. If the male had mated with another female, he could at best divide his time between his two mates and might even devote most of his attention to the alternate mate. Consequently, females enforce monogamy.

Monogamy in birds is also encouraged by the need for the male to secure and defend a territory before he can attract a mate. The male may sing a great deal to announce his presence to females and to discourage rival males from entering his territory. The female moves from one territory to another, seeking a male with foraging territory that offers the best chances for reproductive success. Usually a male is able to defend an area that provides just enough resources for one nesting female.

The most common form of polygamy in birds, when it occurs, is polygyny (“many females”), in which a male mates with more than one female. In many species of grouse, males gather in a collective display ground, the lek, which is divided into individual territories, each vigorously defended by a displaying male (Figure 29-26). There is nothing of value in the lek to the female except the male, and all he can offer are his genes, for only the females care for the young. Usually there are a dominant male and several subordinate males in the lek. Competition among males for females is intense, but females appear to choose the dominant male for mating because, presumably, social rank correlates with genetic quality.

Nesting and Care of Young

To produce offspring, all birds lay eggs that must be incubated by one or both parents. The eggs of most songbirds (order Passeriformes) require approximately 14 days for hatching; those of ducks and geese require at least twice that long. Most of the duties of incubation fall on the female, although in many instances both parents share the task, and occasionally only the male incubates the young.

Most birds build some form of nest in which to rear their young. Some birds simply lay their eggs on the bare ground or rocks, making no pretense of nest building. Others build elaborate nests such as pendant nests constructed by orioles, delicate lichen-covered mud nests of hummingbirds (Figure 29-27) and flycatchers, chimney-shaped mud nests of cliff swallows, floating nests of rednecked grebes, and huge brush-pile nests of Australian brush turkeys. Most birds take considerable pains to conceal their nests from enemies. Woodpeckers, chickadees, bluebirds, and many others place their nests in tree hollows or other cavities; kingfishers excavate tunnels in the banks of streams for their nests; and birds of prey build high in lofty trees or on inaccessible cliffs. Nest parasites such as the brown-headed cowbird and the European cuckoo build no nests at all but simply lay their eggs in the nests of birds smaller than themselves. When the eggs hatch, the foster parents care for the cowbird young which outcompete the host’s own hatchlings.

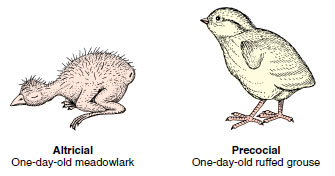

Newly hatched birds are of two types: precocial and altricial. Precocial young, such as quail, fowl, ducks, and most water birds, are covered with down when hatched and can run or swim as soon as their plumage is dry (Figure 29-28). Altricial ones, on the other hand, are naked and helpless at birth and remain in the nest for a week or more. Young of both types require care from parents for some time after hatching. They must be fed, guarded, and protected against rain and sun. Parents of altricial species must carry food to their young almost constantly, for most young birds will eat more than their weight each day. This enormous food consumption explains the rapid growth of the young and their quick exit from the nest. The food of the young, depending on the species, includes worms, insects, seeds, and fruit.

Nesting success is very low with many birds, especially in altricial species. One investigation several years ago of 170 altricial bird nests reported that only 21% produced at least one young. Annual censusing of birds shows that nesting success is even lower today. Of the many causes of nesting failures, predation by raccoons, skunks, opossums, blue jays, crows, and others, especially in suburban and rural woodlots, and nest parasitism by the brown-headed cowbird are the most important factors. Birds of prey probably have a much higher percentage of reproductive success than songbirds.

|

| Figure 29-22 Part of a colony of Northern gannets, Morus bassanus, showing extremely close spacing between pairs in this highly social bird. Order Pelecaniformes. |

The adage says “birds of a feather flock together,” and many birds are indeed highly social creatures. Especially during the breeding season, sea birds gather, often in enormous colonies, to nest and rear young (Figure 29-22). Land birds, with some conspicuous exceptions, such as starlings and rooks, tend to be less gregarious than sea birds during breeding and to seek isolation for rearing their brood. But species that covet separation from their kind during breeding may aggregate for migration or feeding. Togetherness offers advantages: mutual protection from enemies, greater ease in finding mates, less opportunity for individual straying during migration, and mass huddling for protection against low night temperatures during migration. Certain species, such as pelicans (Figure 29-23), may use highly organized cooperative behavior to feed. At no time are the highly organized social interactions of birds more evident than during the breeding season, as they stake out territorial claims, select mates, build nests, incubate and hatch their eggs, and rear their young.

|

| Figure 29-23 Cooperative feeding behavior by the white pelican, Pelecanus onocrotalus. A, Pelicans form a horseshoe to drive fish together. B, Then they plunge simultaneously to scoop fish in their huge bills. These photographs were taken 2 seconds apart. |

|

| Figure 29-24 Copulation in birds. In most bird species the male lacks a penis. The male copulates by standing on the back of the female, pressing his cloaca against that of the female, and passing sperm to the female. |

During most of the year the testes of the male are tiny bean-shaped bodies. But during the breeding season they enlarge greatly, as much as 300 times larger than their nonbreeding size, afterward shrinking again to tiny bodies. Before discharge, the millions of sperm are stored in a seminal vesicle, which, like the testes, enlarges greatly during the breeding season. Since males of most species lack a penis, copulation is a matter of bringing cloacal surfaces into contact, usually while the male stands on the back of the female (Figure 29-24). Some swifts and hawks copulate in flight.

In the female of most birds, only the left ovary and oviduct develop; those on the right dwindle to vestigial structures. Eggs discharged from the ovary are picked up by the expanded end of the oviduct, the infundibulum (Figure 29-25 (below)). The oviduct runs posteriorly to the cloaca. While eggs are passing down the oviduct, albumin, or egg white, from special glands is added to them; farther down the oviduct, the shell membrane, shell, and shell pigments are also secreted about the egg. Fertilization takes place in the upper oviduct several hours before the layers of albumin, shell membranes, and shell are added. Sperm remain alive in the female oviduct for many days after a single mating. Hen eggs show good fertility for 5 or 6 days after mating, but then fertility drops rapidly. However, the occasional egg will be fertile as long as 30 days after separation of the hen from the rooster.

Mating Systems

|

| Figure 29-25 Reproductive system of a female bird. |

The two most common types of mating systems in animals are monogamy, in which an individual mates with only one partner each breeding season, and polygamy, in which an individual mates with two or more partners each breeding period. Monogamy is rare in most animal groups, but in birds it is the general rule: more than 90% are monogamous. In a few bird species such as swans and geese, partners are chosen for life and often remain together throughout the year. Seasonal monogamy is more common, however; the great majority of migrant birds pair up during the breeding season but lead independent lives the rest of the year.

One reason that monogamy is much more common among birds than among mammals is that female birds are not equipped, as mammals are, with a built-in food supply for the young. Accordingly, the ability of the two sexes to provide parental care, especially food for the young, is more equal in birds than in mammals. A female bird will choose a male whose parental investment in their young is apt to be high and avoid a male that has mated with another female. If the male had mated with another female, he could at best divide his time between his two mates and might even devote most of his attention to the alternate mate. Consequently, females enforce monogamy.

Monogamy in birds is also encouraged by the need for the male to secure and defend a territory before he can attract a mate. The male may sing a great deal to announce his presence to females and to discourage rival males from entering his territory. The female moves from one territory to another, seeking a male with foraging territory that offers the best chances for reproductive success. Usually a male is able to defend an area that provides just enough resources for one nesting female.

The most common form of polygamy in birds, when it occurs, is polygyny (“many females”), in which a male mates with more than one female. In many species of grouse, males gather in a collective display ground, the lek, which is divided into individual territories, each vigorously defended by a displaying male (Figure 29-26). There is nothing of value in the lek to the female except the male, and all he can offer are his genes, for only the females care for the young. Usually there are a dominant male and several subordinate males in the lek. Competition among males for females is intense, but females appear to choose the dominant male for mating because, presumably, social rank correlates with genetic quality.

Nesting and Care of Young

To produce offspring, all birds lay eggs that must be incubated by one or both parents. The eggs of most songbirds (order Passeriformes) require approximately 14 days for hatching; those of ducks and geese require at least twice that long. Most of the duties of incubation fall on the female, although in many instances both parents share the task, and occasionally only the male incubates the young.

Most birds build some form of nest in which to rear their young. Some birds simply lay their eggs on the bare ground or rocks, making no pretense of nest building. Others build elaborate nests such as pendant nests constructed by orioles, delicate lichen-covered mud nests of hummingbirds (Figure 29-27) and flycatchers, chimney-shaped mud nests of cliff swallows, floating nests of rednecked grebes, and huge brush-pile nests of Australian brush turkeys. Most birds take considerable pains to conceal their nests from enemies. Woodpeckers, chickadees, bluebirds, and many others place their nests in tree hollows or other cavities; kingfishers excavate tunnels in the banks of streams for their nests; and birds of prey build high in lofty trees or on inaccessible cliffs. Nest parasites such as the brown-headed cowbird and the European cuckoo build no nests at all but simply lay their eggs in the nests of birds smaller than themselves. When the eggs hatch, the foster parents care for the cowbird young which outcompete the host’s own hatchlings.

|

|

|

| Figure 29-26 Dominant male sage grouse, Centrocercus urophasianus, surrounded by several hens that have been attracted by his “booming” display. |

Figure 29-27 Anna’s hummingbird, Calypte anna, feeding its young in its nest of plant down and spiderwebs and decorated on the outside with lichens. The female builds the nest, incubates the two pea-sized eggs, and rears the young with no assistance from the male. Anna’s hummingbird is a common resident of California. It is the only hummer to overwinter in the United States. |

Newly hatched birds are of two types: precocial and altricial. Precocial young, such as quail, fowl, ducks, and most water birds, are covered with down when hatched and can run or swim as soon as their plumage is dry (Figure 29-28). Altricial ones, on the other hand, are naked and helpless at birth and remain in the nest for a week or more. Young of both types require care from parents for some time after hatching. They must be fed, guarded, and protected against rain and sun. Parents of altricial species must carry food to their young almost constantly, for most young birds will eat more than their weight each day. This enormous food consumption explains the rapid growth of the young and their quick exit from the nest. The food of the young, depending on the species, includes worms, insects, seeds, and fruit.

Nesting success is very low with many birds, especially in altricial species. One investigation several years ago of 170 altricial bird nests reported that only 21% produced at least one young. Annual censusing of birds shows that nesting success is even lower today. Of the many causes of nesting failures, predation by raccoons, skunks, opossums, blue jays, crows, and others, especially in suburban and rural woodlots, and nest parasitism by the brown-headed cowbird are the most important factors. Birds of prey probably have a much higher percentage of reproductive success than songbirds.

|

| Figure 29-28 Comparison of 1-day-old altricial and precocial young. The altricial meadowlark (left) is born nearly naked, blind, and helpless. The precocial ruffed grouse (right) is covered with down, alert, strong legged, and able to feed itself. |