Body Plan

Body Plan

The annelid body typically has an anterior prostomium, a segmented body, and a terminal portion bearing the anus (pygidium). The prostomium and pygidium are not considered metameres, but anterior segments often fuse with the prostomium to make up the head. New metameres form during development just in front of the pygidium; thus the oldest segments are at the anterior end and the youngest segments are at the posterior.

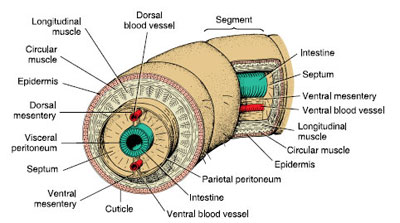

The body wall has strong circular and longitudinal muscles adapted for swimming, crawling, and burrowing and is covered with epidermis and a thin, outer layer of nonchitinous cuticle (Figure 17-1).

In most annelids the coelom develops embryonically as a split in the mesoderm on each side of the gut (schizocoel), forming a pair of coelomic compartments in each segment. Peritoneum (a layer of mesodermal epithelium) lines the body wall of each compartment, forms dorsal and ventral mesenteries, and covers all organs (Figure 17-1). Peritonea of adjacent segments meet to form septa. Septa are perforated by the gut and longitudinal blood vessels. Not only is the coelom metamerically arranged, but practically every body system is affected in some way by this segmental arrangement.

Except in leeches, the coelom is filled with fluid and serves as a hydrostatic skeleton. Because the volume of fluid is essentially constant, contraction of the longitudinal body-wall muscles causes the body to shorten and become larger in diameter, whereas contraction of the circular muscles causes it to lengthen and become thinner. Separation of the hydrostatic skeleton into a metameric series of coelomic cavities increases its efficiency greatly, because the force of local muscle contraction is not transferred throughout the length of the worm. Widening and elongation can occur in restricted areas. Crawling motions are effected by alternating waves of contraction of longitudinal and circular muscles (peristaltic contraction) passing down the body. Segments in which longitudinal muscles are contracted widen and anchor themselves against burrow walls or other substratum while other segments, in which circular muscles are contracted, elongate and stretch forward. Forces powerful enough for burrowing as well as locomotion can thus be generated. Swimming forms use undulatory rather than peristaltic movements in locomotion.

Characteristics of Phylum Annelida

|

| Figure 17-1 Annelid body plan. |

The annelid body typically has an anterior prostomium, a segmented body, and a terminal portion bearing the anus (pygidium). The prostomium and pygidium are not considered metameres, but anterior segments often fuse with the prostomium to make up the head. New metameres form during development just in front of the pygidium; thus the oldest segments are at the anterior end and the youngest segments are at the posterior.

The body wall has strong circular and longitudinal muscles adapted for swimming, crawling, and burrowing and is covered with epidermis and a thin, outer layer of nonchitinous cuticle (Figure 17-1).

In most annelids the coelom develops embryonically as a split in the mesoderm on each side of the gut (schizocoel), forming a pair of coelomic compartments in each segment. Peritoneum (a layer of mesodermal epithelium) lines the body wall of each compartment, forms dorsal and ventral mesenteries, and covers all organs (Figure 17-1). Peritonea of adjacent segments meet to form septa. Septa are perforated by the gut and longitudinal blood vessels. Not only is the coelom metamerically arranged, but practically every body system is affected in some way by this segmental arrangement.

Except in leeches, the coelom is filled with fluid and serves as a hydrostatic skeleton. Because the volume of fluid is essentially constant, contraction of the longitudinal body-wall muscles causes the body to shorten and become larger in diameter, whereas contraction of the circular muscles causes it to lengthen and become thinner. Separation of the hydrostatic skeleton into a metameric series of coelomic cavities increases its efficiency greatly, because the force of local muscle contraction is not transferred throughout the length of the worm. Widening and elongation can occur in restricted areas. Crawling motions are effected by alternating waves of contraction of longitudinal and circular muscles (peristaltic contraction) passing down the body. Segments in which longitudinal muscles are contracted widen and anchor themselves against burrow walls or other substratum while other segments, in which circular muscles are contracted, elongate and stretch forward. Forces powerful enough for burrowing as well as locomotion can thus be generated. Swimming forms use undulatory rather than peristaltic movements in locomotion.

Characteristics of Phylum Annelida

- Body metameric; symmetry bilateral

- Body wall with outer circular and inner longitudinal muscle layers; outer transparent moist cuticle secreted by epithelium

- Chitinous setae often present; setae absent in leeches

- Coelom (schizocoel) well developed and divided by septa, except in leeches; coelomic fluid supplies turgidity and functions as hydrostatic skeleton

- Circulatory system closed and segmentally arranged; respiratory pigments (hemoglobin, hemerythrin, or chlorocruorin) often present; amebocytes in blood plasma

- Digestive system complete and not metamerically arranged

- Respiratory gas exchange through skin, gills, or parapodia

- Excretory system typically a pair of nephridia for each metamere

- Nervous system with a double ventral nerve cord and a pair of ganglia with lateral nerves in each metamere; brain a pair of dorsal cerebral ganglia with connectives to cord

- Sensory system of tactile organs, taste buds, statocysts (in some), photoreceptor cells, and eyes with lenses (in some)

- Hermaphroditic or separate sexes; larvae, if present, are trochophore type; asexual reproduction by budding in some; spiral cleavage and mosaic development