Phylogeny and Adaptive Radiation

Phylogeny and

Adaptive Radiation

Phylogeny

There are so many similarities in early development of molluscs, annelids, and primitive arthropods that few biologists have doubted their close relationship. These three phyla were considered the sister group of flatworms. Many marine annelids and molluscs have an early embryogenesis typical of protostomes, in common with some marine flatworms, and that developmental pattern is probably a shared ancestral trait. Annelids share with arthropods a similar body plan and nervous system, as well as similarities in development. The most important resemblance probably lies in the metameric plans of annelid and arthropod body structures. These longaccepted evolutionary relationships are not supported, however, by a recent hypothesis based on analysis of the base sequence in the gene encoding small-subunit ribosomal RNA, which places annelids and molluscs in a superphylum Lophotrochozoa and arthropods in another protostome superphylum, Ecdysozoa.

Regardless of its relationship to other phyla, Annelida remains a wellaccepted monophyletic group. What can we infer about the common ancestor of annelids? Most hypotheses of annelid origin have assumed that metamerism arose in connection with development of lateral appendages (parapodia) resembling those of polychaetes. However, the oligochaete body is adapted to vagrant burrowing in a substratum with a peristaltic movement that is highly benefited by a metameric coelom. On the other hand, polychaetes with well-developed parapodia are generally adapted to swimming and crawling in a medium too fluid for effective peristaltic locomotion. Although parapodia do not prevent such locomotion, they do little to further it, and they seem likely to have evolved as an adaptation for swimming. Although polychaetes have the most primitive reproductive system, some authorities argue that the ancestral annelids were more similar to the oligochaetes in overall body plan and that those of polychaetes and leeches are more evolutionarily derived. Leeches are closely related to oligochaetes but have diverged from them by having a swimming existence and no burrowing. This relationship is shown by the cladogram in Figure 17-23.

Adaptive Radiation

Annelids are an ancient group that has undergone extensive adaptive radiation. The basic body structure, particularly of polychaetes, lends itself to almost endless modification. As marine worms, polychaetes have a wide range of habitats in an environment that is not physically or physiologically demanding. Unlike earthworms, whose environment imposes strict physical and physiological demands, polychaetes have been free to experiment and thus have achieved a wide range of adaptive features.

A basic adaptive feature in evolution of annelids is their septal arrangement, resulting in fluid-filled coelomic compartments. Fluid pressure in these compartments is used as a hydrostatic skeleton in precise movements such as burrowing and swimming. Powerful circular and longitudinal muscles can flex, shorten, and lengthen the body.

Feeding adaptations show great variation, from the sucking pharynx of oligochaetes and the chitinous jaws of carnivorous polychaetes to the specialized tentacles and radioles of particle feeders.

In polychaetes the parapodia have been adapted in many ways and for a variety of functions, chiefly locomotion and respiration.

In leeches many adaptations, such as suckers, cutting jaws, pumping pharynx, distensible gut, and production of hirudin, relate to their predatory and bloodsucking habits.

Classification of Phylum Annelida

Higher classification of annelids is based primarily on the presence or absence of parapodia, setae, and other morphological features. Because both oligochaetes and hirudineans (leeches) bear a clitellum, these two groups are often placed under the heading Clitellata (cli-tel-la´ta) and members are called clitellates. Alternatively, because both the Oligochaeta and the Polychaeta possess setae, some authorities place them together in a group called Chaetopoda (ke-top´o-da) (N.L. chaeta, bristle, from Gr. chaite, long hair, ´ pous, podos, foot).

Class Polychaeta (pol´e-ke´ta) (Gr. polys, many, + chaite, long hair). Mostly marine; head distinct and bearing eyes and tentacles; most segments with parapodia (lateral appendages) bearing tufts of many setae; clitellum absent; sexes usually separate; gonads transitory; asexual budding in some; trochophore larva usually present; mostly marine. Examples: Nereis, Aphrodita, Glycera, Arenicola, Chaetopterus, Amphitrite.

Class Oligochaeta (ol´i-go-ke´ta) (Gr. oligos, few, + chaite, long hair). Body with conspicuous segmentation; number of segments variable; setae few per metamere; no parapodia; head absent; coelom spacious and usually divided by intersegmental septa; hermaphroditic; development direct, no larva; chiefly terrestrial and freshwater. Examples: Lumbricus, Stylaria, Aeolosoma, Tubifex.

Class Hirudinea (hir´u-din´e-a) (L. hirudo, leech, ´ ea, characterized by): leeches. Body with fixed number of segments (normally 34; 15 or 30 in some groups) with many annuli; oral and posterior suckers usually present; clitellum present; no parapodia; setae absent (except in Acanthobdella); coelom closely packed with connective tissue and muscle; development direct; hermaphroditic; terrestrial, freshwater, and marine. Examples: Hirudo, Placobdella, Macrobdella.

Phylogeny

There are so many similarities in early development of molluscs, annelids, and primitive arthropods that few biologists have doubted their close relationship. These three phyla were considered the sister group of flatworms. Many marine annelids and molluscs have an early embryogenesis typical of protostomes, in common with some marine flatworms, and that developmental pattern is probably a shared ancestral trait. Annelids share with arthropods a similar body plan and nervous system, as well as similarities in development. The most important resemblance probably lies in the metameric plans of annelid and arthropod body structures. These longaccepted evolutionary relationships are not supported, however, by a recent hypothesis based on analysis of the base sequence in the gene encoding small-subunit ribosomal RNA, which places annelids and molluscs in a superphylum Lophotrochozoa and arthropods in another protostome superphylum, Ecdysozoa.

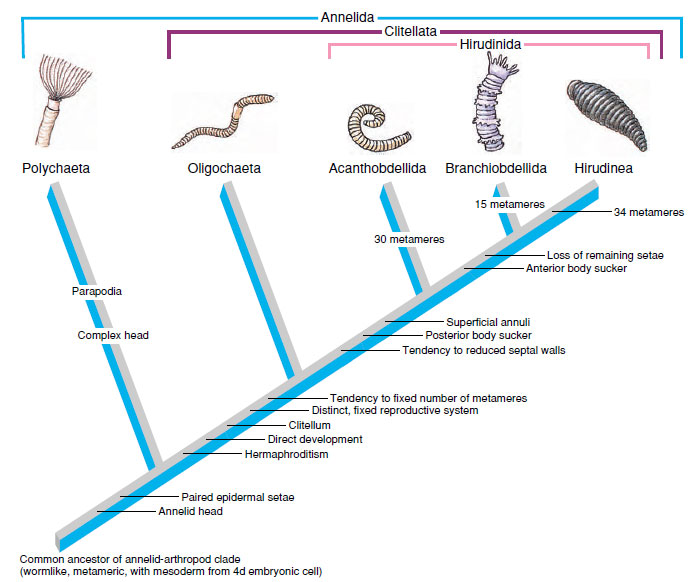

Regardless of its relationship to other phyla, Annelida remains a wellaccepted monophyletic group. What can we infer about the common ancestor of annelids? Most hypotheses of annelid origin have assumed that metamerism arose in connection with development of lateral appendages (parapodia) resembling those of polychaetes. However, the oligochaete body is adapted to vagrant burrowing in a substratum with a peristaltic movement that is highly benefited by a metameric coelom. On the other hand, polychaetes with well-developed parapodia are generally adapted to swimming and crawling in a medium too fluid for effective peristaltic locomotion. Although parapodia do not prevent such locomotion, they do little to further it, and they seem likely to have evolved as an adaptation for swimming. Although polychaetes have the most primitive reproductive system, some authorities argue that the ancestral annelids were more similar to the oligochaetes in overall body plan and that those of polychaetes and leeches are more evolutionarily derived. Leeches are closely related to oligochaetes but have diverged from them by having a swimming existence and no burrowing. This relationship is shown by the cladogram in Figure 17-23.

|

| Figure 17-23 Cladogram of annelids, showing the appearance of shared derived characters that specify the five monophyletic groups (based on Brusca and Brusca, 1990). The Acanthobdellida and the Branchiobdellida are two small groups. Brusca and Brusca place both groups, together with the Hirudinea (“true” leeches), within a single taxon, the Hirudinida. This clade has several synapomorphies: tendency toward reduction of septal walls, the appearance of a posterior sucker, and the subdivision of body segments by superficial annuli. Note also that, according to this scheme, the Oligochaeta have no defining synapomorphies, that is, they are defined solely by retention of plesiomorphies, and thus might be paraphyletic. |

Adaptive Radiation

Annelids are an ancient group that has undergone extensive adaptive radiation. The basic body structure, particularly of polychaetes, lends itself to almost endless modification. As marine worms, polychaetes have a wide range of habitats in an environment that is not physically or physiologically demanding. Unlike earthworms, whose environment imposes strict physical and physiological demands, polychaetes have been free to experiment and thus have achieved a wide range of adaptive features.

A basic adaptive feature in evolution of annelids is their septal arrangement, resulting in fluid-filled coelomic compartments. Fluid pressure in these compartments is used as a hydrostatic skeleton in precise movements such as burrowing and swimming. Powerful circular and longitudinal muscles can flex, shorten, and lengthen the body.

Feeding adaptations show great variation, from the sucking pharynx of oligochaetes and the chitinous jaws of carnivorous polychaetes to the specialized tentacles and radioles of particle feeders.

In polychaetes the parapodia have been adapted in many ways and for a variety of functions, chiefly locomotion and respiration.

In leeches many adaptations, such as suckers, cutting jaws, pumping pharynx, distensible gut, and production of hirudin, relate to their predatory and bloodsucking habits.

Classification of Phylum Annelida

Higher classification of annelids is based primarily on the presence or absence of parapodia, setae, and other morphological features. Because both oligochaetes and hirudineans (leeches) bear a clitellum, these two groups are often placed under the heading Clitellata (cli-tel-la´ta) and members are called clitellates. Alternatively, because both the Oligochaeta and the Polychaeta possess setae, some authorities place them together in a group called Chaetopoda (ke-top´o-da) (N.L. chaeta, bristle, from Gr. chaite, long hair, ´ pous, podos, foot).

Class Polychaeta (pol´e-ke´ta) (Gr. polys, many, + chaite, long hair). Mostly marine; head distinct and bearing eyes and tentacles; most segments with parapodia (lateral appendages) bearing tufts of many setae; clitellum absent; sexes usually separate; gonads transitory; asexual budding in some; trochophore larva usually present; mostly marine. Examples: Nereis, Aphrodita, Glycera, Arenicola, Chaetopterus, Amphitrite.

Class Oligochaeta (ol´i-go-ke´ta) (Gr. oligos, few, + chaite, long hair). Body with conspicuous segmentation; number of segments variable; setae few per metamere; no parapodia; head absent; coelom spacious and usually divided by intersegmental septa; hermaphroditic; development direct, no larva; chiefly terrestrial and freshwater. Examples: Lumbricus, Stylaria, Aeolosoma, Tubifex.

Class Hirudinea (hir´u-din´e-a) (L. hirudo, leech, ´ ea, characterized by): leeches. Body with fixed number of segments (normally 34; 15 or 30 in some groups) with many annuli; oral and posterior suckers usually present; clitellum present; no parapodia; setae absent (except in Acanthobdella); coelom closely packed with connective tissue and muscle; development direct; hermaphroditic; terrestrial, freshwater, and marine. Examples: Hirudo, Placobdella, Macrobdella.