Disjunct Distributions

Disjunct Distributions

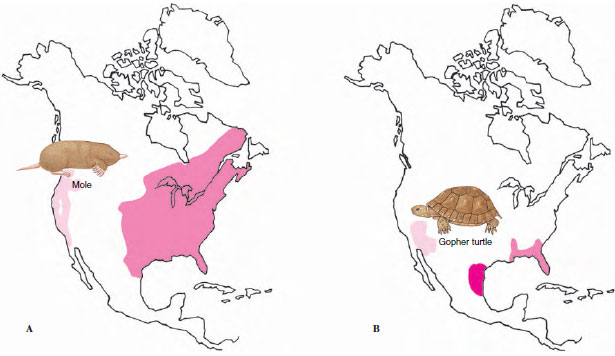

A major problem for zoogeographers is to explain the numerous instances of discontinuous or disjunct distributions: closely related species living in widely separated areas of a continent, or even the world (Figure 39-13). How could a group of animals become so dispersed geographically? There are two possible ways for a disjunct distribution to arise. Either a population moves from its place of origin to a new location (dispersal), traversing intervening territory that is unsuited for long-term colonization, or the environment changes, breaking a once continuously-distributed species into geographically separated populations (vicariance). Vicariance may involve climatic changes that contract and fragment the areas of habitat favorable for a species, or it may involve physical movement of landmasses or waterways that carry different populations of a species away from each other.

A major problem for zoogeographers is to explain the numerous instances of discontinuous or disjunct distributions: closely related species living in widely separated areas of a continent, or even the world (Figure 39-13). How could a group of animals become so dispersed geographically? There are two possible ways for a disjunct distribution to arise. Either a population moves from its place of origin to a new location (dispersal), traversing intervening territory that is unsuited for long-term colonization, or the environment changes, breaking a once continuously-distributed species into geographically separated populations (vicariance). Vicariance may involve climatic changes that contract and fragment the areas of habitat favorable for a species, or it may involve physical movement of landmasses or waterways that carry different populations of a species away from each other.

|

| Figure 39-13 Disjunct distributions in North America. A, Moles of the family Talpidae probably entered North America across the Bering land bridge that once joined North America and Asia during the Tertiary period. Eastern and western populations are now separated by the Rocky Mountains. B, Gopher turtles of the genus Gopherus are now separated into three fully isolated populations. |