Terrestrial Environments: Biomes

|

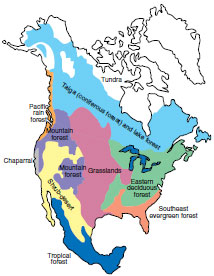

| Figure 39-4 Major biomes of North America. Boundaries between biomes are not distinct as shown but grade into one another over broad areas. |

Terrestrial Environments: Biomes

A biome is a major biotic unit bearing a characteristic and easily recognized array of plant life. Botanists long ago recognized that the terrestrial environment of the earth could be divided into large units having a distinctive vegetation, such as forests, prairies, and deserts. Animal distribution has always been more difficult to map, because plant and animal distributions do not exactly coincide. Over time zoogeographers came to accept plant distributions as the basic biotic units and recognized biomes as distinctive combinations of plants and animals. A biome is therefore identified by its dominant plant formation (Figure 39-4), but, since animals depend on plants, each biome supports a characteristic fauna.

Each biome is distinctive, but its borders are not. Anyone who has traveled across North America knows that plant communities grade into one another over broad areas. The moist deciduous forests of the Appalachians give way gradually to the drier oak forests of the upper Mississippi Valley, and then to oak woodlands with grassy understory. This yields to tall and mixed prairies (now corn and wheatlands), then to desert grasslands, and finally to desert shrublands. The indistinct boundaries where the dominant plants of adjacent biomes are mixed together form an almost continuous gradient called an ecocline. Thus biomes are in some sense abstractions, a convenient way for us to organize our concepts about different communities. Nevertheless, anyone

|

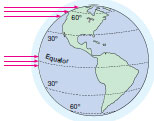

| Figure 39-5 The earth’s climate is determined by differential solar radiation between the higher latitudes and equator. Solar energy is spread across a much larger, slanting surface area at high latitudes than is an equivalent amount of energy at the equator. |

can distinguish a grassland, deciduous forest, coniferous forest, or shrub desert by the dominant plants in each. And we can make reasonable assumptions about the kinds of animals that live in each biome.

Distinctiveness of a biome is determined mainly by climate, the characteristic pattern of rainfall and temperature of each region, and the solar radiation it receives. Global variation in climate arises from uneven heating of the atmosphere by the sun. Because of the lower angle of the sun’s rays striking higher latitudes, atmospheric heating is less there than at the equator (Figure 39-5). Air warmed at the equator rises and moves toward the poles. It is replaced by cold air moving away from the poles at lower levels. This pattern is complicated by the earth’s rotation, which produces a Coriolis effect that deflects moving air to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Air circulation in each hemisphere isbroken into three latitudinal zones, called cells (Figure 39-6). In the Northern Hemisphere, for example, hot moist air at the equator cools and condenses as it rises, providing rainfall for the lush vegetation of the equatorial rain forests. Warm air then flows northward at high levels, cools, and sinks at 20° to 30° latitude. This air is very dry, having lost its moisture at the equator. As it heats it takes up even more moisture, causing intense evaporation at the earth’s surface and producing a subtropical belt of deserts centered between 15° and 30° north (deserts of the American southwest, Saharan Africa, Arabian Peninsula, and India). The air then flows southward toward the equator, picking up moisture as it moves across the ocean,

|

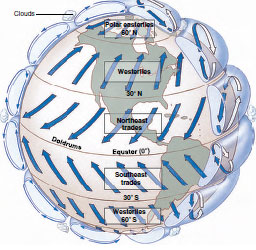

| Figure 39-6 The earth as a heat engine. As the result of unequal heating across the earth’s surface, together with other factors such as the earth’s rotation, circulation of the oceans, and presence of landmasses, the earth acts like a giant heat engine that imposes a complex patchwork of climates on the earth . See text for explanation. |

and being deflected to the right as the northeast trade winds. The cycle in this cell is completed when the air, now laden with moisture, reaches the equator.

A second circulation cell between 30° and 60° north arises when cool air sinking at around 30° moves northward at the surface. At 50° to 60° north it encounters cold air moving south from the North Pole, producing an unstable stormy area with abundant precipitation. The warmer air from the south is deflected upward and turns south at high altitude to complete the second cell. A third, polar cell formswhen cold, southward-moving Arctic air returns to the pole at high altitude.

The principal terrestrial biomes are temperate deciduous forest, temperate coniferous forest, tropical forest, grassland, tundra, and desert. In this brief survey, we will refer especially to the biomes of North America and will consider predominant features of each.