Oceans

Oceans

By almost any measure, oceans represent by far the largest portion of the earth’s biosphere. They cover 71% of the earth’s surface to an average depth of 3.75 km (2.3 miles), with their greatest depths reaching to more than 11.5 km (7.2 miles) below sea level. The marine world is relatively uniform as compared with land, and in many respects it is less demanding on life forms. However, the evident monotony of the ocean’s surface belies the variety of life below. Oceans are the cradle of life, and this is reflected by the variety of organisms living there— more than 200,000 species of unicellular forms, plants, and animals. The vast majority of these forms, about 98%, live on the seabed (benthic); only 2% live freely in the open ocean (pelagic). Of the benthic forms, most occur in the intertidal zone or shallow depths of the oceans. Less than 1% live in the deep ocean below 2000 m.

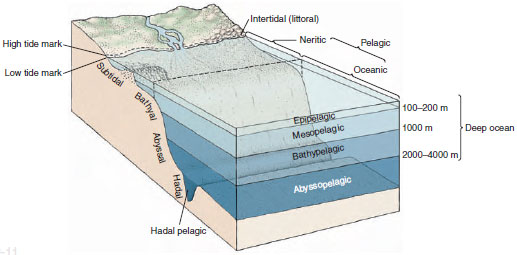

The most productive areas are concentrated along continental margins and a few areas where the waters are enriched by organic nutrients and debris lifted by upwelling currents into the sunlit, or photic, zone, where photosynthetic activity occurs. With certain notable exceptions (see Animal Ecology), all life below the photic zone must be supported by the light “rain” of organic particles from above. Life in the ocean is divided into regions, or provinces, each with its own distinctive life forms (Figures 39-11 and 39-12). The littoral, or intertidal, zone, where sea and land meet, is paradoxically both the harshest and the richest of all marine environments. It, as well as the animals living there, is subjected to pounding surf, sun, wind, rain, extreme temperature fluctuations, erosion, and sedimentation. Yet because of the diversity of available habitats and the bounteous supply of nutrients, animals such as barnacles, snails, chitons, limpets, mussels, sea urchins, sea stars, and many others flourish there. Below the littoral zone is the sublittoral, or subtidal zone, which is always submerged. It also supports a rich variety of animal life, as well as forests of brown algae.

An estuary is a semienclosed transition zone where fresh water flows into the sea. Despite an unstable salinity caused by the variable entry of fresh water, the estuary is a nutrient-rich habitat that supports a diverse fauna.

The neritic, or shallow water, zone surrounds the continents and extends to the edge of the continental shelf—approximately to a depth of 200 m (Figure 39-11). This zone is more productive than the open ocean because it benefits from nutrients delivered by rivers and by upwelling at the edge of the continental shelf. Algal growth is prolific, which in turn supports a diverse animal life, including most of the world’s fisheries.

Areas of upwelling, although small and restricted to a few regions, are vital sources of nutrient renewal for the surface photic zone. Some of the world’s most productive fisheries are— or were—centered on upwelling regions. Before its collapse in 1972, the Peruvian anchovy fishery, which depended on the Peru Current, provided 22% of all fish caught in the world! Earlier, the California sardine fishery and the Japanese herring fishery, both fisheries of upwelling regions, were intensively harvested to the point of collapse and have never recovered. The world’s fisheries today are seriously imperiled due to overfishing, degradation of fish habitats by trawling, wasteful fishing methods, and marine pollution. Some of the world’s greatest fishing grounds, such as the Grand Banks and Georges Banks of eastern North America, have been fished to total collapse. As our demand for food from the sea rises, fish are being extracted much faster than fish populations can reproduce.

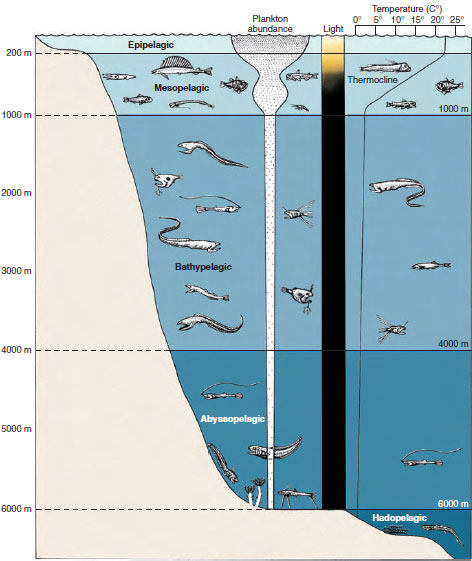

The vast open ocean is known as the pelagic realm (Figure 39-12). Despite its size (comprising 90% of the total oceanic area), the pelagic realm is relatively impoverished biologically because, as organisms die, they sink out of the photic zone, carrying nutrients into the bathypelagic zone where they are immobilized. However, in areas of upwelling and where oceanic currents converge, nutrients are replenished and productivity may be high. The enormously productive polar seas are an example. Before their populations were overexploited by humans, baleen whales probably consumed around 77 million tons of Antarctic krill per year, far more than the entire catch of all fish,crustaceans, and molluscs taken by all the world’s fishing fleet in any single year. The enormous krill population was sustained by phytoplankton, the base of the food chain, which in turn flourished because of the abundance of nutrients in the Antarctic sea.

Below the surface, or epipelagic, layers of the pelagic realm are the great ocean depths, characterized by enormous pressure, perpetual darkness, and a constant temperature near 0° C. It remained a world unknown to humans until recently, when baited cameras, bathyscaphs, and deepwater trawls have been lowered to view and sample the ocean bottom. There are several distinct habitats in the ocean depths (Figure 39-12). The mesopelagic is the “twilight zone,” which receives dim light and supports a varied community of animals. Below the mesopelagic is a world of perpetual darkness, divided into three depth zones as shown in Figure 39- 12: bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadopelagic. Deep-sea forms depend on that meager portion of the gentle rain of organic debris from above that escapes consumption by organisms in the water column. On the sea floor exists the benthos, represented by sea anemones, sea urchins, crustaceans, polychaete worms, and fishes— indeed nearly all major metazoan groups. Most are deposit feeders characterized by very slow growth (because of scarcity of food) and long lives.

Recently self-contained benthic communities of animals that are completely independent of solar energy and the rain of organic debris from above were discovered adjacent to vents of hot water issuing from rifts in the ocean floor (see Animal Ecology).

By almost any measure, oceans represent by far the largest portion of the earth’s biosphere. They cover 71% of the earth’s surface to an average depth of 3.75 km (2.3 miles), with their greatest depths reaching to more than 11.5 km (7.2 miles) below sea level. The marine world is relatively uniform as compared with land, and in many respects it is less demanding on life forms. However, the evident monotony of the ocean’s surface belies the variety of life below. Oceans are the cradle of life, and this is reflected by the variety of organisms living there— more than 200,000 species of unicellular forms, plants, and animals. The vast majority of these forms, about 98%, live on the seabed (benthic); only 2% live freely in the open ocean (pelagic). Of the benthic forms, most occur in the intertidal zone or shallow depths of the oceans. Less than 1% live in the deep ocean below 2000 m.

|

| Figure 39-11 Major marine zones. |

The most productive areas are concentrated along continental margins and a few areas where the waters are enriched by organic nutrients and debris lifted by upwelling currents into the sunlit, or photic, zone, where photosynthetic activity occurs. With certain notable exceptions (see Animal Ecology), all life below the photic zone must be supported by the light “rain” of organic particles from above. Life in the ocean is divided into regions, or provinces, each with its own distinctive life forms (Figures 39-11 and 39-12). The littoral, or intertidal, zone, where sea and land meet, is paradoxically both the harshest and the richest of all marine environments. It, as well as the animals living there, is subjected to pounding surf, sun, wind, rain, extreme temperature fluctuations, erosion, and sedimentation. Yet because of the diversity of available habitats and the bounteous supply of nutrients, animals such as barnacles, snails, chitons, limpets, mussels, sea urchins, sea stars, and many others flourish there. Below the littoral zone is the sublittoral, or subtidal zone, which is always submerged. It also supports a rich variety of animal life, as well as forests of brown algae.

|

| Figure 39-12 Life of the pelagic zones. Each zone supports a distinct community of organisms. Animals in zones below the mesopelagic depend on the meager rain of food that sinks out of the epipelagic and mesopelagic zones. |

An estuary is a semienclosed transition zone where fresh water flows into the sea. Despite an unstable salinity caused by the variable entry of fresh water, the estuary is a nutrient-rich habitat that supports a diverse fauna.

The neritic, or shallow water, zone surrounds the continents and extends to the edge of the continental shelf—approximately to a depth of 200 m (Figure 39-11). This zone is more productive than the open ocean because it benefits from nutrients delivered by rivers and by upwelling at the edge of the continental shelf. Algal growth is prolific, which in turn supports a diverse animal life, including most of the world’s fisheries.

Areas of upwelling, although small and restricted to a few regions, are vital sources of nutrient renewal for the surface photic zone. Some of the world’s most productive fisheries are— or were—centered on upwelling regions. Before its collapse in 1972, the Peruvian anchovy fishery, which depended on the Peru Current, provided 22% of all fish caught in the world! Earlier, the California sardine fishery and the Japanese herring fishery, both fisheries of upwelling regions, were intensively harvested to the point of collapse and have never recovered. The world’s fisheries today are seriously imperiled due to overfishing, degradation of fish habitats by trawling, wasteful fishing methods, and marine pollution. Some of the world’s greatest fishing grounds, such as the Grand Banks and Georges Banks of eastern North America, have been fished to total collapse. As our demand for food from the sea rises, fish are being extracted much faster than fish populations can reproduce.

The vast open ocean is known as the pelagic realm (Figure 39-12). Despite its size (comprising 90% of the total oceanic area), the pelagic realm is relatively impoverished biologically because, as organisms die, they sink out of the photic zone, carrying nutrients into the bathypelagic zone where they are immobilized. However, in areas of upwelling and where oceanic currents converge, nutrients are replenished and productivity may be high. The enormously productive polar seas are an example. Before their populations were overexploited by humans, baleen whales probably consumed around 77 million tons of Antarctic krill per year, far more than the entire catch of all fish,crustaceans, and molluscs taken by all the world’s fishing fleet in any single year. The enormous krill population was sustained by phytoplankton, the base of the food chain, which in turn flourished because of the abundance of nutrients in the Antarctic sea.

Below the surface, or epipelagic, layers of the pelagic realm are the great ocean depths, characterized by enormous pressure, perpetual darkness, and a constant temperature near 0° C. It remained a world unknown to humans until recently, when baited cameras, bathyscaphs, and deepwater trawls have been lowered to view and sample the ocean bottom. There are several distinct habitats in the ocean depths (Figure 39-12). The mesopelagic is the “twilight zone,” which receives dim light and supports a varied community of animals. Below the mesopelagic is a world of perpetual darkness, divided into three depth zones as shown in Figure 39- 12: bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadopelagic. Deep-sea forms depend on that meager portion of the gentle rain of organic debris from above that escapes consumption by organisms in the water column. On the sea floor exists the benthos, represented by sea anemones, sea urchins, crustaceans, polychaete worms, and fishes— indeed nearly all major metazoan groups. Most are deposit feeders characterized by very slow growth (because of scarcity of food) and long lives.

Recently self-contained benthic communities of animals that are completely independent of solar energy and the rain of organic debris from above were discovered adjacent to vents of hot water issuing from rifts in the ocean floor (see Animal Ecology).