Pseudocoelomates

|

| Male Trichinella spiralis, a nematode. |

Without any doubt, nematodes are the most important pseudocoelomate animals, in terms of both numbers and their impact on humans. Nematodes are abundant over most of the world, yet most people are only occasionally aware of them as parasites of humans or of their pets. We are not aware of the millions of these worms in the soil, in ocean and freshwater habitats, in plants, and in all kinds of other animals. Their dramatic abundance moved N. A. Cobb* to write in 1914:

If all the matter in the universe except the nematodes were swept away, our world would still be dimly recognizable, and if, as disembodied spirits, we could then investigate it, we should find its mountains, hills, vales, rivers, lakes and oceans represented by a thin film of nematodes. The location of towns would be decipherable, since for every massing of human beings there would be a corresponding massing of certain nematodes. Trees would still stand in ghostly rows representing our streets and highways. The location of the various plants and animals would still be decipherable, and, had we sufficient knowledge, in many cases even their species could be determined by an examination of their erstwhile nematode parasites.

Position in Animal Kingdom

In the nine phyla covered in this section, the original blastocoel of the embryo persists as a space, or body cavity, between the enteron and body wall. Because this cavity lacks the peritoneal lining found in true coelomates, it is called a pseudocoel, and the animals possessing it are called pseudocoelomates. Pseudocoelomates belong to the Protostomia division of bilateral animals, but they are polyphyletic (derived independently from more than one acoelomate ancestor).

Biological Contributions

- The pseudocoel is a distinct gradation in body plan compared with the solid body structure of acoelomates. The pseudocoel may be filled with fluid or may contain a gelatinous substance with some mesenchyme cells. In common with a true coelom, it presents certain adaptive potentials, although these are by no means realized in all members: (1) greater freedom of movement; (2) space for development and differentiation of digestive, excretory, and reproductive systems; (3) a simple means of circulation or distribution of materials throughout the body; (4) a storage place for waste products to be discharged to the outside by excretory ducts; and (5) a hydrostatic organ. Since most pseudocoelomates are quite small, the most important functions of the pseudocoel are probably in circulation and as a means to maintain a high internal hydrostatic pressure.

- A complete, mouth-to-anus digestive tract is found in these phyla and in all more complex phyla.

Pseudocoelomates

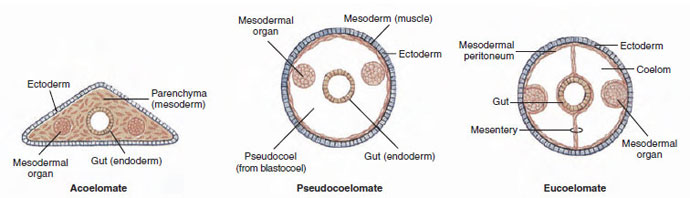

Vertebrates and more complex invertebrates have a true coelom, or peritoneal cavity, which is formed in the mesoderm during embryonic development and is therefore lined with a layer of mesodermal epithelium, the peritoneum (Figure 15-1). Pseudocoelomate phyla have a pseudocoel rather than a true coelom. It is derived from the embryonic blastocoel rather than from a secondary cavity within the mesoderm. It is a space between the gut and the mesodermal and ectodermal components of the body wall, and it is not lined with peritoneum.

|

| Figure 15-1 Acoelomate, pseudocoelomate, and eucoelomate body plans. |

Nine distinct groups of animals belong to the pseudocoelomate category: Rotifera, Gastrotricha, Kinorhyncha, Nematoda, Nematomorpha, Loricifera, Priapulida, Acanthocephala, and Entoprocta. Since the first five of these groups have certain similarities, they formerly were placed as classes in a phylum called Aschelminthes (as´kelmin ´theez) (Gr. askos, bladder, + helmins, worm). However, they differ so much that their phylogenetic relationships are highly debatable, and they are now considered separate phyla. Some group the five loosely as individual phyla under a superphylum Aschelminthes. The Entoprocta have sometimes been grouped with the Ectoprocta, together called the Bryozoa (moss animals). However, because the ectoprocts have a true coelom, they are usually considered a separate phylum, and the term “bryozoans” is currently taken to exclude the entoprocts.

Molecular evidence now suggests that Protostomia is composed of two large groups that diverged in the Precambrian: Lophotrochozoa and Ecdysozoa. Some pseudocoelomate phyla apparently belong in each of these groups.

However one classifies them, pseudocoelomates are a heterogeneous assemblage of animals. Most of them are small; some are microscopic; some are fairly large. Some, such as nematodes, are found in freshwater, marine, terrestrial, and parasitic habitats; others, such as Acanthocephala, are strictly parasitic. Some have unique characteristics, such as the lacunar system of acanthocephalans or the ciliated corona of rotifers.

Even in such a diversified grouping, some characteristics are shared. All have a body wall of epidermis (often syncytial), a dermis, and muscles surrounding the pseudocoel. The digestive tract is complete (except in Acanthocephala), and it, along with gonads and excretory organs, is within the pseudocoel and bathed in perivisceral fluid. The epidermis in many secretes a nonliving cuticle with some specializations such as bristles or spines.

A constant number of cells or nuclei in individuals of a species, or in parts of their bodies, is known as eutely, which is common to several of the groups. In most of them there is an emphasis on the longitudinal muscle layer.