Superclass Agnatha: Jawless Fishes

Superclass Agnatha:

Jawless Fishes

Living jawless fishes are represented by approximately 84 species divided between two classes: Myxini (hagfishes) with about 43 species and Cephalaspidomorphi (lampreys) with 41 species (Figures 26-3 and 26-4). Members of both groups lack jaws, internal ossification, scales, and paired fins, and both groups share porelike gill openings and an eel-like body form. In other respects, however, the two groups are morphologically very different. Hagfishes are certainly the least derived of the two, while lampreys bear many derived morphological characters that place them phylogenetically much closer to gnathostomes than to hagfishes. Because of these differences, hagfishes and lampreys have been assigned to separate vertebrate classes, leaving the grouping “agnatha” as a paraphyletic assemblage of jawless fishes.

Class Myxini: Hagfishes Hagfishes are an entirely marine group that feeds on annelids, molluscs, crustaceans, and dead or dying fishes. Thus they are not parasitic like lampreys but are scavengers and predators. There are 43 described species of hagfishes, of which the best known in North America are the Atlantic hagfish Myxine glutinosa (Gr. myxa, slime) (Figure 26-3) and the Pacific hagfish Eptatretus stouti (N. L. ept, Gr. hepta, seven + tretos, perforated). Although almost completely blind, the hagfish is quickly attracted to food, especially dead or dying fishes, by its keenly developed senses of smell and touch. The hagfish enters a dead or dying animal through an orifice or by digging inside. Using two toothed, keratinized plates on the tongue that fold together in a pincerlike action, the hagfish rasps away bits of flesh from its prey. For extra leverage, the hagfish often ties a knot in its tail, then passes it forward along the body until it is pressed securely against the side of its prey.

Hagfishes are renowned for their ability to generate enormous quantities of slime. If disturbed or roughly handled, the hagfish exudes a milky fluid from special glands positioned along the body. On contact with seawater, the fluid forms a slime so slippery that the animal is almost impossible to grasp.

Unlike any other vertebrate, the body fluids of hagfishes are in osmotic equilibrium with seawater, as in most marine invertebrates. Hagfishes have several other anatomical and physiological peculiarities, including a lowpressure circulatory system served by three accessory hearts in addition to the main heart positioned behind the gills.

The reproductive biology of hagfishes remains largely a mystery, despite a still unclaimed prize offered more than 100 years ago by the Copenhagen Academy of Science for information on the animal’s breeding habits. It is known that females, which in some species outnumber males 100 to one, produce small numbers of surprisingly large, yolky eggs 2 to 7 cm in diameter depending on the species. There is no larval stage.

Characteristics of Class Myxini

Class Cephalaspidomorphi (Petromyzontes): Lampreys

All the lampreys of the Northern Hemisphere belong to the family Petromyzontidae (Gr. petros, stone, + myzon, sucking). The group name refers to the lamprey’s habit of grasping a stone with its mouth to hold position in a current. The destructive marine lamprey Petromyzon marinus is found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean (in America and Europe) and may attain a length of 1 m (Figure 26-4). Lampetra (L. lambo, to lick or lap up) also has a wide distribution in North America and Eurasia and ranges from 15 to 60 cm long. There are 22 species of lampreys in North America. About half of these belong to the nonparasitic brook type; the others are parasitic. The genus Ichthyomyzon (Gr. ichthyos, fish, + myzon, sucking), which includes three parasitic and three nonparasitic species, is restricted to eastern North America. On the west coast of North America the chief marine form is Lampetra tridentatus.

All lampreys ascend freshwater streams to breed. The marine forms are anadromous (Gr. anadromos, running upward); that is, they leave the sea where they spend their adult lives to swim up streams to spawn. In North America all lampreys spawn in winter or spring. Males begin nest building and are joined later by females. Using their oral discs to lift stones and pebbles and vigorous body vibrations to sweep away light debris, they form an oval depression (Figure 26-5). At spawning, with the female attached to a rock to maintain her position over the nest, the male attaches to the dorsal side of her head. As eggs are shed into the nest, they are fertilized by the male. The sticky eggs adhere to pebbles in the nest and quickly become covered with sand. The adults die soon after spawning.

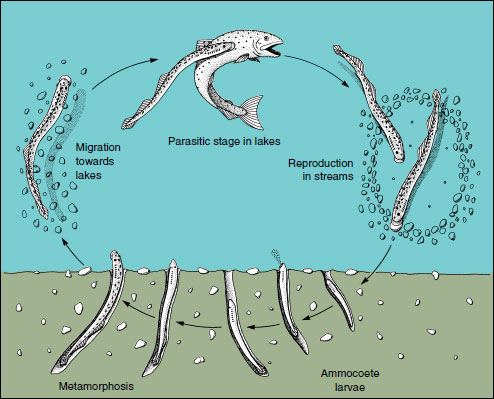

The eggs hatch in about 2 weeks,

releasing small larvae (ammocoetes),

which are so unlike their parents that

early biologists thought they were

a separate species. The larva bears a

remarkable resemblance to amphioxus

and possesses the basic chordate

characteristics in such simplified and

easily visualized form that it has been

considered a chordate archetype. After absorbing the remainder

of its yolk supply, the young

ammocoete, now about 7 mm long,

leaves the nest gravel and drifts

downstream to burrow in some suitable

sandy, low-current area. The

larva takes up a suspension-feeding

existence while growing slowly for 3

to 7 or more years, then rapidly metamorphoses

into an adult. This change

involves the eruption of eyes, replacement

of the hood by the oral disc with

keratinized teeth, enlargement of fins,

maturation of gonads, and modification

of the gill openings.

Parasitic lampreys either migrate to the sea, if marine, or remain in fresh water, where they attach themselves by their suckerlike mouth to a fish and, with their sharp keratinized teeth, rasp away the flesh and suck out body fluids (Figure 26-6). To promote the flow of blood, the lamprey injects an anticoagulant into the wound. When gorged, the lamprey releases its hold but leaves the fish with a large, gaping wound that is sometimes fatal. The parasitic freshwater adults live 1 to 2 years before spawning and then die; the anadromous forms live 2 to 3 years.

Nonparasitic lampreys do not feed after emerging as adults and their alimentary canal degenerates to a nonfunctional strand of tissue. Within a few months they also spawn and die.

The invasion of the Great Lakes by the landlocked sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus in this century has had a devastating effect on the fisheries. No lampreys were present in the Great Lakes west of Niagara Falls until the Welland Ship Canal was built in 1829. Even then nearly 100 years elapsed before sea lampreys were first seen in Lake Erie. After that the sea lamprey spread rapidly and was causing extraordinary damage in all the Great Lakes by the middle 1940s. No fish species was immune from attack, but the lampreys preferred lake trout, and this multimillion dollar fishing industry was brought to total collapse in the late 1950s. Lampreys then turned to rainbow trout, whitefish, burbot, yellow perch, and lake herring, all important commercial species. These stocks were decimated in turn. The lampreys then began attacking chubs and suckers. Coincident with decline in attacked species, sea lampreys themselves began to decline after reaching a peak abundance in 1951 in Lakes Huron and Michigan and in 1961 in Lake Superior. The fall has been attributed both to depletion of food and to the effectiveness of control measures (mainly chemical larvicides in selected spawning streams). Lake trout, aided by a restocking program, are now recovering. Wounding rates are low in Lake Michigan but still high in some lakes. Fishery organizations are now experimenting with the release of sterilized male lampreys into spawning streams; when fertile females mate with sterilized males the female’s eggs fail to develop.

Characteristics of Class Cephalaspidomorphi

Characteristics of Class Chondrichthyes

Living jawless fishes are represented by approximately 84 species divided between two classes: Myxini (hagfishes) with about 43 species and Cephalaspidomorphi (lampreys) with 41 species (Figures 26-3 and 26-4). Members of both groups lack jaws, internal ossification, scales, and paired fins, and both groups share porelike gill openings and an eel-like body form. In other respects, however, the two groups are morphologically very different. Hagfishes are certainly the least derived of the two, while lampreys bear many derived morphological characters that place them phylogenetically much closer to gnathostomes than to hagfishes. Because of these differences, hagfishes and lampreys have been assigned to separate vertebrate classes, leaving the grouping “agnatha” as a paraphyletic assemblage of jawless fishes.

|

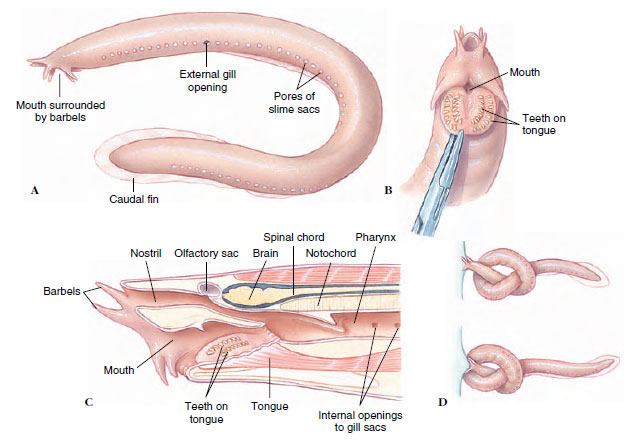

| Figure 26-3 The Atlantic hagfish Myxine glutinosa (class Myxini). A, External anatomy; B, Ventral view of head, showing horny plates used to grasp food during feeding; C, Sagittal section of head region (note retracted position of rasping tongue and internal openings into a row of gill sacs); D, Hagfish knotting, showing how it obtains leverage to tear flesh from prey. |

Class Myxini: Hagfishes Hagfishes are an entirely marine group that feeds on annelids, molluscs, crustaceans, and dead or dying fishes. Thus they are not parasitic like lampreys but are scavengers and predators. There are 43 described species of hagfishes, of which the best known in North America are the Atlantic hagfish Myxine glutinosa (Gr. myxa, slime) (Figure 26-3) and the Pacific hagfish Eptatretus stouti (N. L. ept, Gr. hepta, seven + tretos, perforated). Although almost completely blind, the hagfish is quickly attracted to food, especially dead or dying fishes, by its keenly developed senses of smell and touch. The hagfish enters a dead or dying animal through an orifice or by digging inside. Using two toothed, keratinized plates on the tongue that fold together in a pincerlike action, the hagfish rasps away bits of flesh from its prey. For extra leverage, the hagfish often ties a knot in its tail, then passes it forward along the body until it is pressed securely against the side of its prey.

Hagfishes are renowned for their ability to generate enormous quantities of slime. If disturbed or roughly handled, the hagfish exudes a milky fluid from special glands positioned along the body. On contact with seawater, the fluid forms a slime so slippery that the animal is almost impossible to grasp.

Unlike any other vertebrate, the body fluids of hagfishes are in osmotic equilibrium with seawater, as in most marine invertebrates. Hagfishes have several other anatomical and physiological peculiarities, including a lowpressure circulatory system served by three accessory hearts in addition to the main heart positioned behind the gills.

The reproductive biology of hagfishes remains largely a mystery, despite a still unclaimed prize offered more than 100 years ago by the Copenhagen Academy of Science for information on the animal’s breeding habits. It is known that females, which in some species outnumber males 100 to one, produce small numbers of surprisingly large, yolky eggs 2 to 7 cm in diameter depending on the species. There is no larval stage.

Characteristics of Class Myxini

- Body slender, eel-like, rounded, with naked skin containing slime glands

- No paired appendages, no dorsal fin (the caudal fin extends anteriorly along the dorsal surface)

- Fibrous and cartilaginous skeleton; notochord persistent

- Biting mouth with two rows of eversible teeth

- Heart with sinus venosus, atrium, and ventricle; accessory hearts, aortic arches in gill region

- Five to 16 pairs of gills with a variable number of gill openings

- Segmented mesonephric kidney; marine, body fluids isosmotic with seawater

- Digestive system without stomach; no spiral valve or cilia in intestinal tract

- Dorsal nerve cord with differentiated brain; no cerebellum; 10 pairs of cranial nerves; dorsal and ventral nerve roots united

- Sense organs of taste, smell, and hearing; eyes degenerate; one pair semicircular canals

- Sexes separate (ovaries and testes in same individual but only one is functional); external fertilization; large yolky eggs, no larval stage

|

| Figure 26-4 Sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus, feeding on the body fluids of a dying fish. |

Class Cephalaspidomorphi (Petromyzontes): Lampreys

All the lampreys of the Northern Hemisphere belong to the family Petromyzontidae (Gr. petros, stone, + myzon, sucking). The group name refers to the lamprey’s habit of grasping a stone with its mouth to hold position in a current. The destructive marine lamprey Petromyzon marinus is found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean (in America and Europe) and may attain a length of 1 m (Figure 26-4). Lampetra (L. lambo, to lick or lap up) also has a wide distribution in North America and Eurasia and ranges from 15 to 60 cm long. There are 22 species of lampreys in North America. About half of these belong to the nonparasitic brook type; the others are parasitic. The genus Ichthyomyzon (Gr. ichthyos, fish, + myzon, sucking), which includes three parasitic and three nonparasitic species, is restricted to eastern North America. On the west coast of North America the chief marine form is Lampetra tridentatus.

All lampreys ascend freshwater streams to breed. The marine forms are anadromous (Gr. anadromos, running upward); that is, they leave the sea where they spend their adult lives to swim up streams to spawn. In North America all lampreys spawn in winter or spring. Males begin nest building and are joined later by females. Using their oral discs to lift stones and pebbles and vigorous body vibrations to sweep away light debris, they form an oval depression (Figure 26-5). At spawning, with the female attached to a rock to maintain her position over the nest, the male attaches to the dorsal side of her head. As eggs are shed into the nest, they are fertilized by the male. The sticky eggs adhere to pebbles in the nest and quickly become covered with sand. The adults die soon after spawning.

|

| Figure 26-5 Life cycle of the “landlocked” form of the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus. |

|

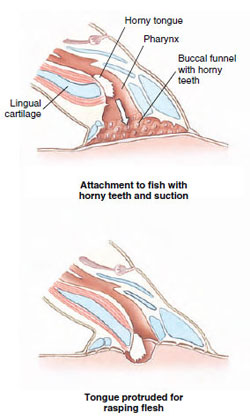

| Figure 26-6 How the lamprey uses its horny tongue to feed. After firmly attaching to a fish by its sucker, the protrusible tongue rapidly rasps an opening through the fish’s integument. Body fluid, abraded skin, and muscle are eaten. |

Parasitic lampreys either migrate to the sea, if marine, or remain in fresh water, where they attach themselves by their suckerlike mouth to a fish and, with their sharp keratinized teeth, rasp away the flesh and suck out body fluids (Figure 26-6). To promote the flow of blood, the lamprey injects an anticoagulant into the wound. When gorged, the lamprey releases its hold but leaves the fish with a large, gaping wound that is sometimes fatal. The parasitic freshwater adults live 1 to 2 years before spawning and then die; the anadromous forms live 2 to 3 years.

Nonparasitic lampreys do not feed after emerging as adults and their alimentary canal degenerates to a nonfunctional strand of tissue. Within a few months they also spawn and die.

The invasion of the Great Lakes by the landlocked sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus in this century has had a devastating effect on the fisheries. No lampreys were present in the Great Lakes west of Niagara Falls until the Welland Ship Canal was built in 1829. Even then nearly 100 years elapsed before sea lampreys were first seen in Lake Erie. After that the sea lamprey spread rapidly and was causing extraordinary damage in all the Great Lakes by the middle 1940s. No fish species was immune from attack, but the lampreys preferred lake trout, and this multimillion dollar fishing industry was brought to total collapse in the late 1950s. Lampreys then turned to rainbow trout, whitefish, burbot, yellow perch, and lake herring, all important commercial species. These stocks were decimated in turn. The lampreys then began attacking chubs and suckers. Coincident with decline in attacked species, sea lampreys themselves began to decline after reaching a peak abundance in 1951 in Lakes Huron and Michigan and in 1961 in Lake Superior. The fall has been attributed both to depletion of food and to the effectiveness of control measures (mainly chemical larvicides in selected spawning streams). Lake trout, aided by a restocking program, are now recovering. Wounding rates are low in Lake Michigan but still high in some lakes. Fishery organizations are now experimenting with the release of sterilized male lampreys into spawning streams; when fertile females mate with sterilized males the female’s eggs fail to develop.

Characteristics of Class Cephalaspidomorphi

- Body slender, eel-like, rounded with naked skin

- One or two median fins, no paired appendages

- Fibrous and cartilaginous skeleton; notochord persistent

- Suckerlike oral disc and tongue with well-developed keratinized teeth

- Heart with sinus venosus, atrium, and ventricle; aortic arches in gill region

- Seven pairs of gills each with external gill opening

- Opisthonephric kidney; anadromous and fresh water; body fluids osmotically and ionically regulated

- Dorsal nerve cord with differentiated brain, small cerebellum present; 10 pairs cranial nerves; dorsal and ventral nerve roots separated

- Digestive system without stomach; intestine with spiral fold

- Sense organs of taste, smell, hearing; eyes well developed in adult; two pairs semicircular canals

- Sexes separate; single gonad without duct; external fertilization; long larval stage (ammocoete)

Characteristics of Class Chondrichthyes

- Large (average about 2 m), body fusiform, or dorsoventrally depressed, with a heterocercal caudal fin (diphycercal in chimaeras) (Figure 26-16); paired pectoral and pelvic fins, two dorsal median fins; pelvic fins in male modified for “claspers”

- Mouth ventral; two olfactory sacs that do not open into the mouth cavity in elasmobranchs; nostrils open into mouth cavity in chimaeras; jaws modified from pharyngeal arch

- Skin with placoid scales or naked in elasmobranchs (Figure 26-18); skin naked in chimaeras; teeth of modified placoid scales and serially replaced in elasmobranchs; teeth modified as grinding plates in chimaeras

- Endoskeleton entirely cartilaginous; notochord persistent but reduced; vertebrae complete and separate in elasmobranchs; vertebrae present but centra absent in chimaeras; appendicular, girdle, and visceral skeletons present; cranium sutureless

- Digestive system with J-shaped stomach (stomach absent in chimaeras); intestine with spiral valve; often with large oil-filled liver for buoyancy

- Circulatory system of several pairs of aortic arches; dorsal and ventral aorta, capillary and venous systems, hepatic portal and renal portal systems; four-chambered heart with sinus venosus, atrium, ventricle, and conus arteriosus

- Respiration by means of five to seven pairs of gills leading to exposed gill slits in elasmobranchs; four pairs of gills covered by an operculum in chimaeras

- No swim bladder or lung

- Opisthonephric kidney and rectal gland; blood isosmotic or slightly hyperosmotic to sea water; high concentrations of urea and trimethylamine oxide in blood

- Brain of two olfactory lobes, two cerebral hemispheres, two optic lobes, cerebellum, medulla oblongata; 10 pairs of cranial nerves; three pairs of semicircular canals

- Senses of smell, vibration reception (lateral line system), vision, and electroreception well developed; inner ear opens to outside via endolymphatic duct

- Sexes separate; gonads paired; reproductive ducts open into cloaca (separate urogenital and anal openings in chimaeras); oviparous, ovoviviparous, or viviparous; direct development; fertilization internal