Types of Tissues

Types of Tissues

A tissue is a group of similar cells (together with associated cell products) specialized for the performance of a common function. The study of tissues is called histology (Gr. histos, tissue, + logos, discourse). All cells in metazoan animals take part in the formation of tissues. Sometimes cells of a tissue may be of several kinds, and some tissues have a great many intercellular materials.

During embryonic development, the germ layers become differentiated into four kinds of tissues. These are epithelial, connective, muscular, and nervous tissues (Figure 9-3). This is a surprisingly short list of only four basic tissue types that are able to meet the diverse requirements of animal life.

Epithelial Tissue

An epithelium (pl., epithelia) is a sheet of cells that covers an external or internal surface. Outside the body, the epithelium forms a protective covering. Inside, the epithelium lines all organs of the body cavity, as well as ducts and passageways through which various materials and secretions move. On many surfaces epithelial cells are modified into glands that produce lubricating mucus or specialized products such as hormones or enzymes.

Epithelia are classified on the basis of cell form and number of cell layers. Simple epithelia (Figure 9-4) are found in all metazoan animals, while stratified epithelia (Figure 9-5) are mostly restricted to vertebrates. All types of epithelia are supported by an underlying basement membrane, which is a condensation of the ground substance of connective tissue. Blood vessels never penetrate into epithelial tissues, which depend on diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from underlying tissues.

Connective Tissue

Connective tissues are a diverse group of tissues that serve various binding and supportive functions. They are so widespread in the body that removal of other tissues would still leave the complete form of the body clearly apparent. Connective tissue is composed of relatively few cells, a great many extracellular fibers, and a ground substance (also called matrix), in which the fibers are embedded. We recognize several different types of connective tissue. Two kinds of connective tissue proper occur in vertebrates. Loose connective tissue is composed of fibers and both fixed and wandering cells suspended in a syrupy ground substance. Dense connective tissue, such as tendons and ligaments, is composed largely of densely packed fibers (Figure 9-6). Much of the fibrous tissue of connective tissue is composed of collagen (Gr. kolla, glue, + genos, descent), a protein material of great tensile strength. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the animal kingdom, found in animal bodies wherever both flexibility and resistance to stretching are required. Connective tissue of invertebrates, as in vertebrates, consists of cells, fibers, and ground substance, but it is not as elaborately developed.

Other types of connective tissue include blood, lymph, and tissue fluid (collectively considered vascular tissue), composed of distinctive cells in a fluid ground substance, the plasma. Vascular tissue lacks fibers under normal conditions. Cartilage is a semirigid form of connective tissue with closely packed fibers embedded in a gel-like ground substance (matrix). Bone is a calcified connective tissue containing calcium salts organized around collagen fibers (see Figure 9-6).

Muscular Tissue

Muscle is the most abundant tissue in the body of most animals. It originates (with few exceptions) from mesoderm, and its unit is the cell or muscle fiber, specialized for contraction. When viewed with a light microscope, striated muscle appears transversely striped (striated), with alternating dark and light bands (Figure 9-7). In vertebrates we recognize two types of striated muscle: skeletal and cardiac muscle. A third kind of muscle is smooth (or visceral) muscle, which lacks the characteristic alternating bands of the striated type (Figure 9-7). The unspecialized cytoplasm of muscles is called sarcoplasm, and contractile elements within the fiber are myofibrils.

Nervous Tissue

Nervous tissue is specialized for reception of stimuli and conduction of impulses from one region to another. Two basic types of cells in nervous tissue are neurons (Gr. nerve), the basic functional unit of the nervous system, and neuroglia (nu-rog`le-a; Gr. nerve, + glia, glue), a variety of nonnervous cells that insulate neuron membranes and serve various supportive functions. Figure 9-8 shows the functional anatomy of a typical nerve cell.

A tissue is a group of similar cells (together with associated cell products) specialized for the performance of a common function. The study of tissues is called histology (Gr. histos, tissue, + logos, discourse). All cells in metazoan animals take part in the formation of tissues. Sometimes cells of a tissue may be of several kinds, and some tissues have a great many intercellular materials.

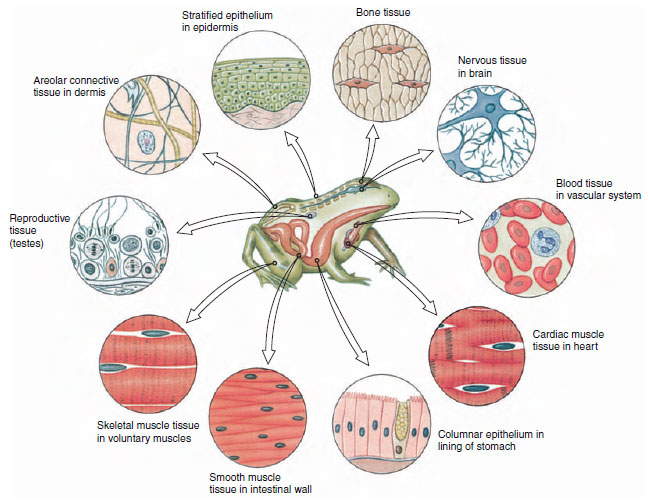

During embryonic development, the germ layers become differentiated into four kinds of tissues. These are epithelial, connective, muscular, and nervous tissues (Figure 9-3). This is a surprisingly short list of only four basic tissue types that are able to meet the diverse requirements of animal life.

|

| Figure 9-3 Types of tissues in a vertebrate, showing examples of where different tissues are located in a frog. |

Epithelial Tissue

An epithelium (pl., epithelia) is a sheet of cells that covers an external or internal surface. Outside the body, the epithelium forms a protective covering. Inside, the epithelium lines all organs of the body cavity, as well as ducts and passageways through which various materials and secretions move. On many surfaces epithelial cells are modified into glands that produce lubricating mucus or specialized products such as hormones or enzymes.

|

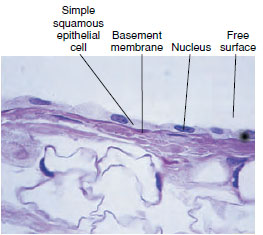

Simple squamous epithelium, composed of flattened cells that form a continuous delicate lining of blood capillaries, lungs, and other surfaces where it permits the passive diffusion of gases and tissue fluids into and out of cavities. |

|

|

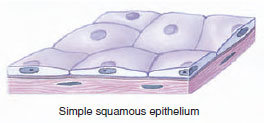

| Simple cuboidal epithelium is composed of short, boxlike cells. Cuboidal epithelium usually lines small ducts and tubules, such as those of the kidney and salivary glands, and may have active secretory or absorptive functions. |

|

|

|

|

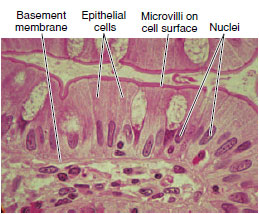

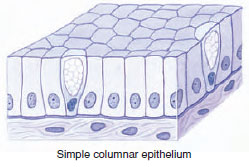

Simple columnar epithelium resembles cuboidal epithelium, but the cells are taller and usually have elongate nuclei. This type of epithelium is found in highly absorptive surfaces such as the intestinal tract of most animals. The cells often bear minute, fingerlike projections called microvilli that greatly increase the absorptive surface. In some organs, such as the female reproductive tract, the cells are ciliated. |

|

|

| Figure 9-4 Types of simple epithelium. |

|

Epithelia are classified on the basis of cell form and number of cell layers. Simple epithelia (Figure 9-4) are found in all metazoan animals, while stratified epithelia (Figure 9-5) are mostly restricted to vertebrates. All types of epithelia are supported by an underlying basement membrane, which is a condensation of the ground substance of connective tissue. Blood vessels never penetrate into epithelial tissues, which depend on diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from underlying tissues.

|

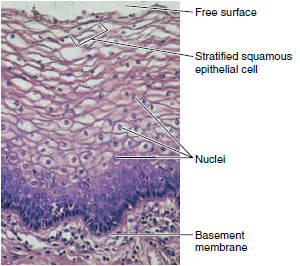

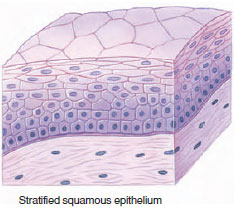

Stratified squamous epithelium consists of two to many layers of cells adapted to withstand mild mechanical abrasion. The basal layer of cells undergoes continuous mitotic divisions, producing cells that are pushed toward the surface where they are sloughed off and replaced by new cells from beneath. This type of epithelium lines the oral cavity, esophagus, and anal canal of many vertebrates, and the vagina of mammals. |

|

|

|

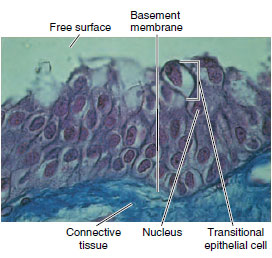

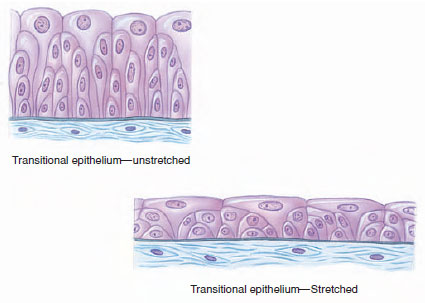

Transitional epithelium is a type of stratified epithelium specialized to accommodate great stretching. This type of epithelium is found in the urinary tract and bladder of vertebrates. In the relaxed state it appears to be four or five cell layers thick, but when stretched out it appears to have only two or three layers of extremely flattened cells. |

|

|

| Figure 9-5 Types of stratified epithelium. |

|

Connective Tissue

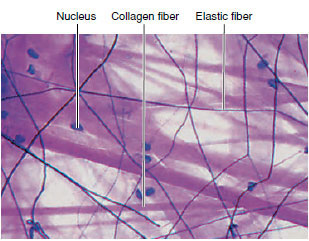

Connective tissues are a diverse group of tissues that serve various binding and supportive functions. They are so widespread in the body that removal of other tissues would still leave the complete form of the body clearly apparent. Connective tissue is composed of relatively few cells, a great many extracellular fibers, and a ground substance (also called matrix), in which the fibers are embedded. We recognize several different types of connective tissue. Two kinds of connective tissue proper occur in vertebrates. Loose connective tissue is composed of fibers and both fixed and wandering cells suspended in a syrupy ground substance. Dense connective tissue, such as tendons and ligaments, is composed largely of densely packed fibers (Figure 9-6). Much of the fibrous tissue of connective tissue is composed of collagen (Gr. kolla, glue, + genos, descent), a protein material of great tensile strength. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the animal kingdom, found in animal bodies wherever both flexibility and resistance to stretching are required. Connective tissue of invertebrates, as in vertebrates, consists of cells, fibers, and ground substance, but it is not as elaborately developed.

|

|

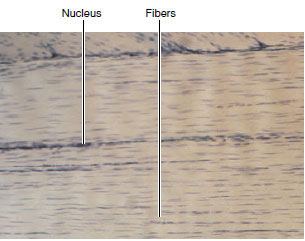

| Loose connective tissue, also called areolar connective tissue, is the “packing material” of the body that anchors blood vessels, nerves, and body organs. It contains fibroblasts that synthesize the fibers and ground substance of connective tissue and wandering macrophages that phagocytize pathogens or damaged cells. The different fiber types include strong collagen fibers (thick and red in micrograph) and thin elastic fibers (black and branching in micrograph) formed of the protein elastin. Adipose (fat) tissue is considered a type of loose connective tissue. | Dense connective tissue forms tendon, ligaments, and

fasciae

(fa´sha), the latter arranged as sheets or

bands of tissue

surrounding skeletal muscle. In tendon (shown here) the collagenous fibers are extremely long and tightly packed together. |

|

|

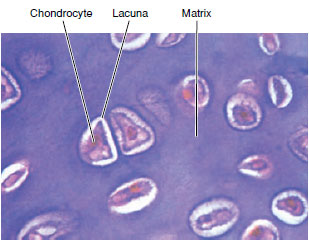

| Cartilage is a vertebrate connective tissue composed of a firm gel ground substance (matrix) containing cells (chondrocytes) living in small pockets called lacunae, and collagen or elastic fibers (depending on the type of cartilage). In hyaline cartilage shown here, both collagen fibers and matrix are stained uniformly purple and cannot be distinguished one from the other. Because cartilage lacks a blood supply, all nutrients and waste materials must diffuse through the ground substance from surrounding tissues. |

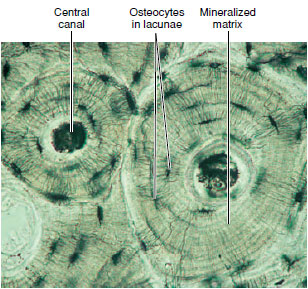

Bone, the strongest of vertebrate connective tissues,

contains

mineralized collagen fibers. Small pockets (lacunae) within the matrix contain bone cells, called osteocytes. The osteocytes communicate with blood vessels that penetrate into bone by means of a tiny network of channels called canaliculi. Unlike artilage, bone undergoes remodeling during an animal’s life, and can repair itself following even extensive damage. |

| Figure 9-6 Types of connective tissue. |

|

Other types of connective tissue include blood, lymph, and tissue fluid (collectively considered vascular tissue), composed of distinctive cells in a fluid ground substance, the plasma. Vascular tissue lacks fibers under normal conditions. Cartilage is a semirigid form of connective tissue with closely packed fibers embedded in a gel-like ground substance (matrix). Bone is a calcified connective tissue containing calcium salts organized around collagen fibers (see Figure 9-6).

|

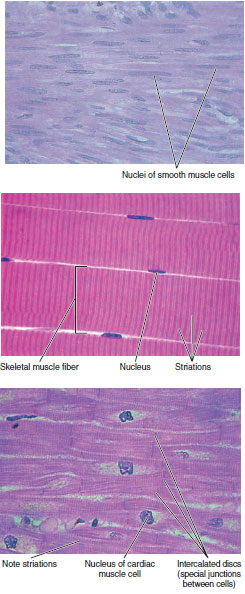

Smooth muscle is nonstriated muscle found in both invertebrates and vertebrates. Smooth muscle cells are long, tapering strands, each containing a single nucleus. Smooth muscle is the most common type of muscle in invertebrates in which it serves as body wall musculature and lines ducts and sphincters. In vertebrates, smooth muscle lines the walls of blood vessels and surrounds internal organs such as the intestine and uterus. It is called involuntary muscle in vertebrates since its contraction is usually not consciously controlled. |

|

Skeletal muscle is a type of striated muscle found in both invertebrates and

vertebrates.

It is composed of extremely long, cylindrical fibers, which are

multinucleate

cells that may reach from one end of the muscle to the other.

Viewed through the light

microscope, the cells appear to have a series of

stripes, called striations, running

across them. Skeletal muscle is called voluntary

muscle (in vertebrates) because it

contracts when stimulated by nerves under

conscious cerebral control. |

||

Cardiac muscle is another type of striated muscle found only in the vertebrate

heart.

The cells are much shorter than those of skeletal muscle and have only

one nucleus

per cell (uninucleate). Cardiac muscle tissue is a branching network

of fibers with individual

cells interconnected by junctional complexes called

intercalated discs. Cardiac

muscle is considered involuntary muscle because it

does not require nerve activity to

stimulate contraction. Instead, heart rate is

controlled by specialized pacemaker cells

located in the heart itself. However,

autonomic nerves from the brain may alter pacemaker

activity. |

||

| Figure 9-7 Types of muscle tissue. |

||

Muscular Tissue

|

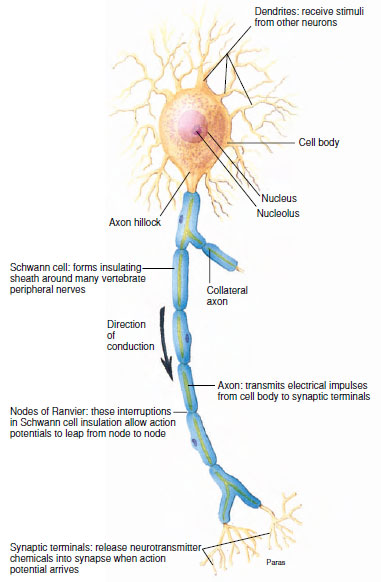

| Figure 9-8 Functional anatomy of a neuron. From the nucleated cell body, or soma, extend one or more dendrites (Gr. dendron, tree), which receive electrical impulses from receptors or other nerve cells, and a single axon that carries impulses away from the cell body to other nerve cells or to an effector organ. The axon is often called a nerve fiber. Nerves are separated from other nerves or from effector organs by specialized junctions called synapses. |

Muscle is the most abundant tissue in the body of most animals. It originates (with few exceptions) from mesoderm, and its unit is the cell or muscle fiber, specialized for contraction. When viewed with a light microscope, striated muscle appears transversely striped (striated), with alternating dark and light bands (Figure 9-7). In vertebrates we recognize two types of striated muscle: skeletal and cardiac muscle. A third kind of muscle is smooth (or visceral) muscle, which lacks the characteristic alternating bands of the striated type (Figure 9-7). The unspecialized cytoplasm of muscles is called sarcoplasm, and contractile elements within the fiber are myofibrils.

Nervous Tissue

Nervous tissue is specialized for reception of stimuli and conduction of impulses from one region to another. Two basic types of cells in nervous tissue are neurons (Gr. nerve), the basic functional unit of the nervous system, and neuroglia (nu-rog`le-a; Gr. nerve, + glia, glue), a variety of nonnervous cells that insulate neuron membranes and serve various supportive functions. Figure 9-8 shows the functional anatomy of a typical nerve cell.