Scales

Scales can be defined as organic or inorganic surface structures of distinct size and shape. Scales

can be distributed individually or arranged in a pattern sometimes forming an envelope around the cell. They occur only in eukaryotic algae, in the divisions of Heterokontophyta, Haptophyta,

and Chlorophyta. They can be as large as the scales of Haptophyta (1 mm), but also as small as

the scales of Prasynophyceae (Chlorophyta) (50 nm). There are at least three distinct types of

scales: non-mineralized scales, made up entirely of organic matter, primarily polysaccharides,

which are present in the Prasynophyceae (Chlorophyta); scales consisting of calcium carbonate

crystallized onto an organic matrix, as the coccoliths produced by many Haptophyta; and scales

constructed of silica deposited on a glycoprotein matrix, formed by some members of the

Heterokontophyta.

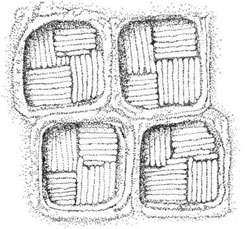

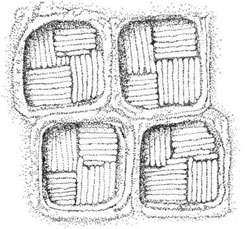

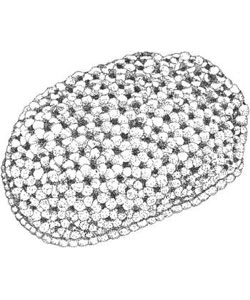

Most taxa of the Prasinophyceae (Chlorophyta) possess several scale types per cell, arranged in

1–5 layers on the surface of the cell body and flagella, those of each layer having a unique morphology for that taxon. These scales consist mainly of acidic polysaccharides involving unusual

2-keto sugar acids, with glycoproteins as minor components. Members of the order Pyramimonadales

exhibit one of the most complex scaly covering among the Prasinophyceae. It consists of three

layers of scales. The innermost scales are small, square, or pentagonal; the intermediate scales are

either naviculoid, spiderweb-shaped, or box shaped (Figure 2.4); the outer layer consists of large

basket or crown-shaped scales. It is generally accepted that scales of the Prasinophyceae are synthesized within the Golgi apparatus; developing scales are transported through the Golgi apparatus

by cisternal progression to the cell surface and released by exocytosis. In some Prasynophyceae

genera such as Tetraselmis and Scherffelia, the cell body is covered entirely by fused scales. The

scale composition consists mainly of acidic polysaccharides. These scales are produced only

during cell division. They are formed in the Golgi apparatus and their development follow the

route already described for the scales. After secretion, scales coalesce extracellularly inside the parental covering to form a new cell wall.

FIGURE 2.4 Box shaped scales of the intermediate layer of Pyramimonas sp. cell body covering.

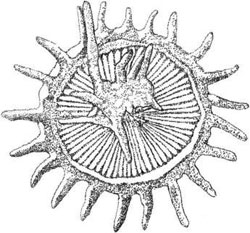

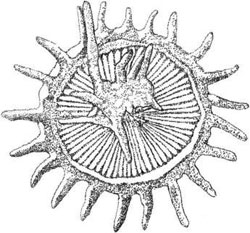

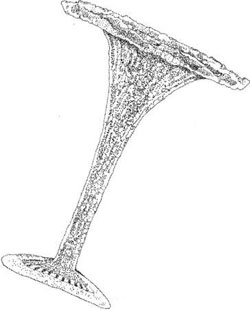

FIGURE 2.5 Elaborate body scale of Chrysochromulina sp.

In the Haptophyta, cells are typically covered with external scales of varying degree of complexity,

which may be unmineralized or calcified. The unmineralized scales consist largely of

complex carbohydrates, including pectin-like sulfated and carboxylated polysaccharides, and

cellulose-like polymers. The structure of these scales varies from simple plates to elaborate,

spectacular spines and protuberances, as in Chrysochromulina sp. (Figure 2.5) or to the unusual

spherical or clavate knobs present in some species of Pavlova.

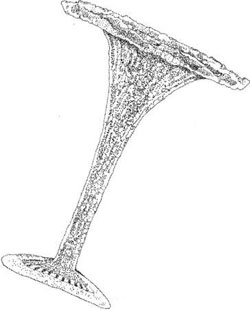

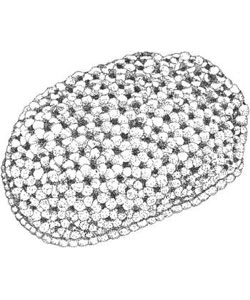

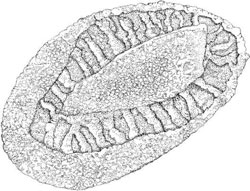

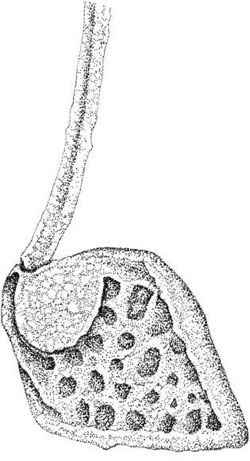

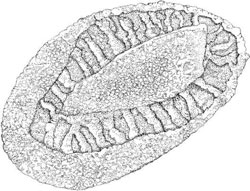

Calcified scales termed coccoliths are produced by the coccolithophorids, a large group of species within the Haptophyta. In terms of ultrastructure and biomineralization processes, two very different types of coccoliths are formed by these algae: heterococcoliths, (Figure 2.6) and holococcoliths (Figure 2.7). Some life cycles include both heterococcolith and holococcolithproducing forms. In addition, there are a few haptophytes that produce calcareous structures that do not appear to have either heterococcolith or holococcolith ultrastructure. These may be products of further biomineralization processes, and the general term nannolith is applied to them.

FIGURE 2.6 Heterococcolith of Discosphaera tubifera.

FIGURE 2.7 Holococcolith of Syracosphaera oblonga.

Heterococcoliths are the most common coccolith type, which mainly consist of radial arrays of

complex crystal units. The sequence of heterococcolith development has been described in detail in

Pleurochrysis carterae, Emiliana huxleyi, and the non-motile heterococcolith phase of Coccolithus

pelagicus. Despite the significant diversity in these observations, a clear overall pattern is discernible in all cases. The process commences with formation of a precursor organic scale inside Golgiderived vesicles; calcification occurs within these vesicles with nucleation of a protococcolith ring of simple crystals around the rim of the precursor base-plate scale. This is followed by growth of

these crystals in various directions to form complex crystal units. After completion of the coccolith,

the vesicle dilates, its membrane fuses with the cell membrane and exocytosis occur. Outside the

cell, the coccolith joins other coccoliths to form the coccosphere, that is the layer of coccoliths

surrounding the cell.

Holococcoliths consist of large numbers of minute morphologically simple crystals. Studies have

been performed on two holococcolith-forming species, the motile holococcolith phase of Coccolithus

pelagicus and Calyptrosphaera sphaeroidea. Similar to the heteroccoliths, the holococcoliths are underlain by base-plate organic scales formed inside Golgi vesicles. However, holococcolith calcification is an extracellular process. Experimental evidences revealed that calcification occurs in a single highly regulated space outside the cell membrane, but directly above the stack of Golgi vesicles. This extracellular compartment is covered by a delicate organic envelope or “skin.” The cell secretes calcite that fills the space between the skin and the base-plate scales. The coccosphere grows progressively outward from this position. As a consequence of the different biomineralization strategies, heterococcoliths are more robust than the smaller and more delicate holococcoliths.

Coccolithophorids, together with corals and foraminifera, are responsible for the bulk of

oceanic calcification.

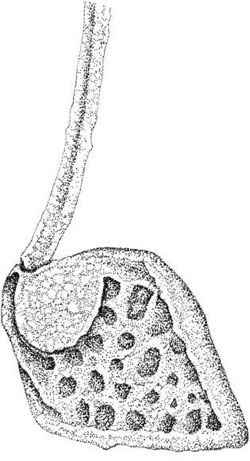

Members of the Chrysophyceae (Heterokontophyta) such as Synura sp. and Mallomonas sp. are

covered by armor of silica scales, with a very complicated structure. Synura scales consists of a

perforated basal plate provided with ribs, spines, and other ornamentation (Figure 2.8). In

Mallomonas, scales may bear long, complicated bristles (Figure 2.9). Several scale types are produced

in the same cell and deposited on the surface in a definite sequence, following an imbricate,

often screw-like pattern. Silica scales are produced internally in deposition vesicles formed by the

chrysoplast endoplasmic reticulum, which function as moulds for the scales. Golgi body vesicles

transporting material fuse with the scale-producing vesicles. Once formed the scale is extruded

from the cell and brought into correct position on the cell surface.

FIGURE 2.8 Ornamented body scale of Synura petersenii.

FIGURE 2.9 Body scale of Mallomonas crassisquama.