The Development of the Vertebrata

The ova of Vertebrata have the same primary composition as those of other animals, consisting of a germinal vesicle, containing one or many germinal spots, and included within a vitellus, upon the amount of which the very variable size of the vertebrate ovum chiefly depends. The vitellus is surrounded by a vitelline membrane, and this may receive additional investments in the form of layers of albumen, and of an outer, coriaceous, or calcified shell.The spermatozoa are always actively mobile, and, save in some rare and exceptional cases, are developed in distinct individuals from those which produce ova.

Impregnation may take place, either subsequently to the extrusion of the egg, when, of course, the whole development of the young goes on outside the body of the oviparous parent; or it may occur before the extrusion of the egg. In the latter case, the development of the egg in the interior of the body may go no further than the formation of a patch of primary tissue; as in birds, where the so-called cicatricula, or "tread," which is observable in the new-laid egg, is of this nature. Or, the development of the young may be completed while the egg reinains in the interior of the body of the parent, but quite free and unconnected with it; as in those vertebrates which are termed ovoviviparous. Or, the young may receive nourishment from its viviparous parent, before birth, by the close apposition of certain vascular appendages of its body to the walls of the cavity in which it undergoes its development.

When development takes place outside the body, it may be independent of parental aid, as in ordinary fishes; but, among some reptiles and in most birds, the parent supplies the amount of heat, in excess of the ordinary temperature of the air, which is required, from its own body, by the process of incubation.

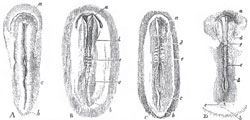

The first step in the development of the embryo is the division of the vitelline substance into cleavage-masses, of which there are at first two, then four, then eight, and so on. The germinal vesicle is no longer seen, but each cleuvagemass contains a nucleus. The cleavage-masses eventually become very small, and are called embryo-cells, as the body of the embryo is built up out of them. The process of yelkdivision may be either complete or partial. In the former case, it, from the first, affects the whole yelk; in the latter, it commences in part of the yelk, and gradually extends to the rest. The blastoderm, or embryogenic tissue in which it results, very early exhibits two distinguishable strata-an inner, the so-called mucous stratum (hypoblast), which gives rise to the epithelium of the alimentary tract; and an outer, the serous stratum (epiblast), from which the epidermis and the cerebro-spinal nervous centres are evolved. Between these appears the intermediate stratun (mesoblast), which gives rise to all the structures (save the brain and spinal marrow) which, in the adult, are included between the epidermis of the integument and the epithelium of the alimentary tract and its appendages.

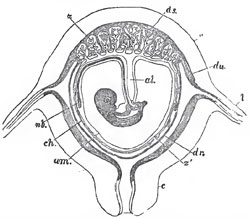

The part of the blastoderm vrhich lies external to the dorsal laminae forms the ventral laminae; and these bend downward and inward, at a short distance on either side of the dorsal tube, to become the vraUs of a ventral, or visceral, tube. The ventral laminag carry the epiblast on their outer surfaces, and the hypoblast on their inner surfaces, and thus, in most cases, tend to constrict off the central from the peripheral portions of the blastoderm. The latter, extending over the yelk, encloses it in a kind of bag. This bag is the first-formed and the most constant of the temporary, or foetal, appendages of the young vertebrate, the umbilical vesicle.

While these changes are occurring, the mesoblast splits, throughout the regions of the thorax and abdomen, from its ventral margin, nearly up to the notochord (which has been developed, in the mean whUe, by histological differentiation of the axial indifferent tissue, immediately under the floor of the primitive groove), into two lamelloe. One of these, the visceral lamella, remains closely adherent to the hypoblast, forming with it the splanchnopleure, and eventually becomes the proper wall of the enteric canal ; while the other, the parietal lamella, follows the epiblast, forming with it the somatopleure, which is converted into the parietes of the thorax and abdomen. The point of the middle line of the abdomen at which the somatopleures eventually unite, is the umbilicus.

The walls of the cavity formed by the splitting of the ventral laminae acquire an epithelial lining, and become the great pleuroperitoneal serous membranes.