The Foetal Appendages of the Vertebrata

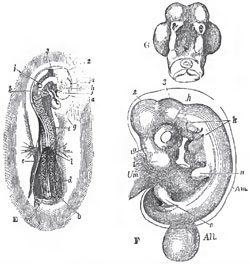

At its outer margin, that part of the somatopleure which is to be converted into the thoracic and abdominal wall of the embryo, grows up anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally, over the body of the embryo. The free margins of this fold gradually approach one another, and, ultimately uniting, the inner layer of the fold becomes converted into a sac filled with a clear fluid, the Amnion; while the outer laj'er either disappears or coalesces with the vitelline membrane, to form the ChorionThus the amnion encloses the body of the embryo, but not the umbilical sac. At most, as the constricted neck, which unites the umbilical sac with the cavity of the future intestine, becomes narrowed and elongated into the vitelline duct, and as the sac itself diminishes in relative size, the amnion, increasing in absolute and relative dimensions, and becoming distended with fluid, is reflected over it (Fig. 1).

A third foetal appendage, the Allantois, commences as a single or double outgrowth from the under surface of the mesoblast, behind the alimentary tract; but soon takes the fonn of a vesicle, and receives the ducts of the primordial kidneys, or Wolffian bodies. It is supplied with blood by two arteries, called hypogastric, which spring from the aorta; and it varies very much in its development. It may become so large as to invest all the rest of the embryo, in the respiratory, or nutritive, processes of which it then takes an important share.

Reptiles, birds, and mammals have all these foetal appendages. At birth, or when the egg is hatched, the amnion bursts and is thrown off, and so much of the allantois as lies outside the walls of the body is similarly exuviated; but that part of it which is situated within the body is very generally converted, behind and below, into the urinary bladder, and, in front and above, into a ligamentous cord, the urachus, which connects the bladder with the front wall of the abdomen. The umbilical vesicle may either be cast off, or taken into the interior of the body and gradually absorbed.

The majority of the visceral clefts of fishes and of many Amphibia remain open throughout life; and the visceral arches of all fishes (except Amphioxus), and of all Amphibia, throw out filamentous or lamellar processes, which receive branches from the aortic arches, and, as branchice, subserve respiration. In other Vertebrata all the visceral clefts become closed and, with the frequent exception of the first, obliterated; and no branchise are developed upon any of the visceral arches.

In all vertebrated animals, a system of relatively or absolutely hard parts affords protection, or support, to the softer tissues of the body. These, according as they are situated upon the surface of the body, or are deeper seated, are called exoskeleton, or endosheleton.