The Spinal System

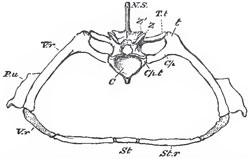

The protovertebrae consist at first of mere indifferent tissue; and it is by a process of histological differentiation within the protovertebral masses that, from its deeper parts, one of the spinal ganglia and a cartilaginous vertebral centrum - from its superficial layer, a segment of the dorsal muscles, are produced.Chondrification extends upward into the walls of the dorsal tube, to produce the neural arch and spine of each vertebra; and, outward, into the wall of the thoracic and abdominal part of the ventral tube, to give rise to the transverse processes and ribs. In fishes, the latter remain distinct and separate from one another, at their distal ends ; but, in most reptiles, in birds, and in mammals, the ends of some of the anterior ribs, on both sides, unite together, and then the united parts coalesce in the middle line to form a median subthoracic cartilage - the sternum.

When ossification sets in, the centra of the vertebra are usually ossified, in great measure, from ringlike deposits hich closely invest the notochord; the arches, from two lateral deposits, which may extend more or less into the centrum. The vertebral and the sternal portions of a rib may each have a separate ossific centre, and become distinct bones; or the sternal parts may remain always cartilaginous. The sternum itself is variously ossified.

Between the completely-ossified condition of the vertebral column and its earliest state, there are a multitude of gradations, most of which are more or less completely realized in the adult condition of certain vertebrated animals. The vertebral column may be represented by nothing but a notochord with a structureless, or more or less fibrous, or cartilaginous sheath, with or without rudiments of cartilaginous arches and ribs. Or there may be bony rings, or ensheathing ossifications, in its walls; or it may have ossified neural arches and ribs only, without cartilaginous or osseous centra. The vertebrae may be completely ossified, with very deeply biconcave bodies, the notochord remaining persistent in the doubly - conical intervertebral substance; or, ossification may extend, so as to render the centrum concave on one surface and convex on the other, or even convex at each end.

Vertebrae which have centra concave at each end have been conveniently termed amphicoelus; those with a cavity in front and a convexity behind, procoelus; where the position of the concavity and convexity is reversed, they are opisthocoelous.

The centra of the vertebrae may be united together by synovial joints, or by ligamentous fibres - the intervertebral ligaments. The arches are connected by ligaments, and generally, in addition, by overlapping articular processes called zygapophyses, or oblique processes.

In a great many Vertebrata, the first and second cervical, or atlas and axis, vertebrae undergo a singular change; the central ossification of the body of the atlas not coalescing with its lateral and inferior ossifications, but either persisting as a distinct os odontoideum,or an chylosing with the body of the axis, and becoming the so-called odontoid process of this vertebra.

In Vertebrata with well-developed hind-limbs, one or more vertebrae, situated at the posterior part of the trunk, usually become peculiarly modified, and give rise to a sacrum, with which the pelvic arch is connected by the intermediation of expanded and anchylosed ribs. In front of the sacrum the vertebrae are artificially classed as cervical, dorsal, and lumbar. The first vertebra, the ribs of which are connected with the sternum, is dorsal, and all those which lie behind it, and have distinct ribs, are dorsal. Vertebrae without distinct ribs, between the last dorsal and the sacrum, are lumbar. Vertebrae, with or without ribs, in front of the first dorsal are cervical.

The vertebrae which lie behind the sacrum are caudal or coccygeal. Very frequently, downward processes of these vertebrae enclose the backward continuation of the aorta, and may be separately ossified as subcaudal, or chevron, bones.

In the majority of the. Vertebrata, the caudal vertebra gradually diminish in size toward the extremity of the body, and become reduced, by the non-development of osseous processes or arches, to mere centra. But, in many fishes, which possess well-ossified trunk-vertebrae, no distinct centra are developed at the extremity of the caudal region, and the notochord, invested in a more or less thickened, fibrous, or cartilaginous sheath, persists. Not withstanding this embryonio condition of the axis of the tail, the superior and inferior arches, and the interspinous bones, may be completely formed in cartilage or bone.

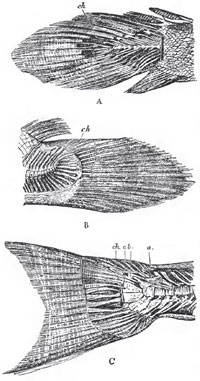

Whatever the condition of the extreme end of the spine of a fish, it occasionally retains the same direction as the trunk part, but is far more generally bent up, so as to form an obtuse angle with the latter. In the former case, the extremity of the spine divides the caudal fin-rays into two nearly equal moieties, an upper and a lower, and the fish is said to be diphycercal (Fig. 6, A). In the latter case, the upper division of the caudal fin-rays is much smaller than the lower, and the fish is heterocercal (Fig. 6, B, C).

In most osseous fishes the hypural bones wnich support the fin-rays of the inferior division become much expanded, and either remain separate, or coalesce into a wedge-shaped, nearly symmetrical bone, which becomes anchylosed with the last ossified vertebral centrum. The inferior fin-rays are now disposed in such a manner as to give the tail an appearance of symmetry with respect to the axis of the body, and such fishes have been called homocercal. Of these homocercal fish, some (as the Salmon, Fig. 6) have the notochord unossified, and protected only by bony plates developed at its sides. In others (as the Stickleback, Perch, etc.), the sheath of the notochord becomes completely ossified and united with the centrum of the last vertebra, which then appears to be prolonged into a bony urostyle