The Modifications of the Brain

The chief modifications in the general form of the brain arise from the development of the hemispheres relatively to the other parts. In the lower vertebrates the hemispheres remain small, or of so moderate a size as not to hide, by overlapping, the other divisions of the brain. But, in the higher Mammalia, they extend forward over the olfactory lobes, and backward over the optic lobes and cerebellum, so as completely to cover these parts; and, in addition, they are enlarged downward toward the base of the brain. The cerebral hemisphere is thus, as it were, bent round its carpus striatum, and it becomes distinguished into regions, or lohes, which are not separated by any very sharp lines of demarcation. These regions are named the frontal, parietal occipital, and temporal lobes - while, on the outer side of the corpus striatum, a central lobe (the insula of Reil) lies in the midst of these. The lateral ventricles are prolonged into the frontal, occipital, and temporal lobes, and acquire what are termed their anterior, posterior, and descending cornua.Furthermore, while, in the lower vertebrates, the surface of the cerebral hemispheres is smooth; in the higher, it becomes complicated by ridges and furrows, the gyri and sulci, which follow particular patterns. The superficial vascular layer of connective tissue which covers the brain, and is called pia mater, dips into these sulci: but the arachnoid, or delicate serous membrane, which, on the one hand, covers the brain, and, on the other, lines the cranium, passes from convolution to convolution without entering the sulci. The dense periosteal membrane which lines the interior of the skull, and is itself lined by the parietal layer of the arachnoid, goes by the name of the dura mater.

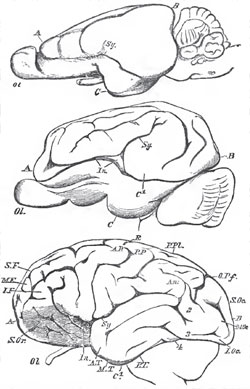

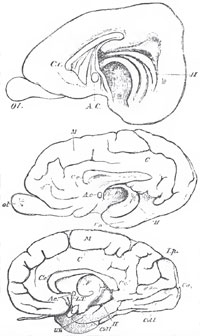

The general nature of the modifications observable in the brain as we pass from the lower to the higher mammalia is very well shown by the accompanying figures of the brain of a Rabbit, a Pig, and a Chimpanzee (Figs. 21 and 22).

In the Rabbit, the cerebral hemispheres leave the cerebellum completely exposed when the brain is viewed from above. There is but a mere rudiment of the Sylvian fissure at Sy, and the three principal lobes, frontal (A), occipital (B), and temporal (C), are only indicated. The olfactory nerves are enormous, and pass by a broad smooth tract, which occupies a great space in the lateral aspect of the brain, into the natiform protuberance of the temporal lobe (C).

In the Pig, the olfactory nerves and tract are hardly less conspicuous; but the natiform protuberance is more sharply notched off, and begins to resemble the uneiform gyrus in the higher Mammalia, of which it is the homologue. The temporal gyri (C1), though still very small, begin to enlarge downward and forward over this. The upper part of the cerebral hemisphere is much enlarged, not only in the frontal, but also in the occipital region, and to a great extent hides the cerebellum when the brain is viewed from above.

What in the Rabbit was a mere angulation at Sy, in the Pig has become among sulcus - the Sylvian fissure, the lips of which are formed by a gyrus, the Sylvian, or angular, gyrus.

In the Chimpanzee, the olfactory nerves, or rather lobes, are, relatively, very small, and the tracts which connect them with the uncinate gyri (substantce perforatice) are completely hidden by the temporal gyri (C1). The Sylvian fissure is very long and deep, and begins to hide the insula, on which a few fan-shaped gyri are developed. The frontal lobes are very large, and overlap the olfactory nerves for a long distance; while the occipital lobes complelely cover and extend beyond the cerebellum, so as to hide it completely from an eye placed above. The gyri and sulci have now attained an arrangement which is characteristic of all the highest Mammalia. The fissure of Rolando (R) divides the antero-parietal gyrus (A.P) from the postero-parietal (P.P). These two gyri, with the postero-parietal lobule (P.Pl), and part of the angular gyrus (An), constitute the Parietal lobe. The frontal lobe, which lies anterior to this, the occipital lobe, which lies behind it, and the temporal lobe, which lies below it, each present three tiers of gyri, which, in the case of the frontal and occipital lobes, are called superior, middle, and inferior - in that of the temporal lobe, anterior, middle, and posterior. The inferior surface of the frontal lobe, which lies on the roof of the orbit (S. Or.), presents many small salci and gyri.

On the inner face of the cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 22) the oly sulcus presented by the Rabbit's brain is that deep and broad depression (H) which runs parallel with the posterior pillar of the fornix, and gives rise, in the interior of the descending cornu of the lateral ventricle, to the projection which is termed the hippocampus major. In the Pig, this hippocampal sulcus (H) is much narrower and less conspicuous; and a marginal (M) and a calossal (C) gyrus are separated by a well-marked calloso-marginal sulcus. As in the Rabbit, the uncinate gyrus forms the inferior boundary of the hemisphere. In the Chimpanzee, the marginal and callosal gyri are still better marked. There is a deep internal perpendicular, or occipito-parietal, sulcus (I.p). The calcarine sulcus (Ca) causes a projection into the floor of the posterior cornu, which is the hippocampms minor; while the collateral sukus (Coll) gives rise to the eminence of that name in both the posterior and descending cornua. The hippocampal sulcus (H) is relatively insignificant, and the lower edge of the temporal lobe is formed by the posterior temporal gyrus.

In the Rabbit, the corpus callosum is relatively small, much inclined upward and backward; and its anterior extremity is but slightly bent downward, so that the so-called genu and rostrum are inconspicuous. The Pig's corpus callosum is larger, more horizontal, and possesses more of a rostrum in the Chimpanzee, it is still larger, somewhat deflexed, and very thick posteriorly; and has a large rostrum. In proportion to the hemispheres, the anterior commissure is largest in the Rabbit and smallest in the Chimpanzee. The Rabbit and the Pig have a single corpus mammillare, the Chimpanzee has two. The cerebellum of the Rabbit is very large in proportion to the hemispheres, and is left completely uncovered by them in the dorsal view. Its median division, or vermis, is straight, symmetrical, and large in proportion to the lateral lobes. The flocculi, or accessory lobules developed from the latter, are large, and project far beyond the margins of the lateral lobes. The ventral face of the metencephalon presents on each side, behind the posterior margin of the pons varolii, flattened rectangular areae, the so-called corpora trapezoidea.

In the Pig, the cerebellum is relatively smaller, and is partially covered by the hemispheres; the lateral lobes are larger in proportion to the vermis and the flocouli, and extend over the latter. The corpora trapezoidea are smaller. In the Chimpanzee, the relatively still smaller cerebellum is completely covered; the vermis is very small in relation to the lateral lobes, which cover and hide the insignificant flocculi. There are no corpora trapezoidea.

In all the characters now mentioned, the brain of Man differs far less from that of the Chimpanzee than that of the latter does from the Pig's brain.