The Reproductive Organs

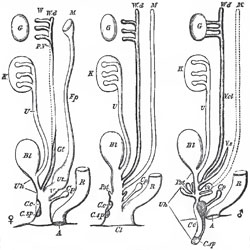

These, in vertebrated animals, are primitively similar in both sexes, and arise on the inner side of the Wolffian bodies, and in front of the kidneys, in the abdominal cavity. In the female the organ becomes an ovarium. This, in some few fishes, sheds its ova, as soon as they are ripened, into the peritoneal cavity, whence they escape by abdominal pores, which place that cavity in direct communication with the exterior. In many fishes, the ovaries become tubular glands, provided with continuous ducts, which open externally, above and behind the anus. But, in all other Vertebrata, the ovaries are glands without continuous ducts, and which discharge their ova from sacs, the Graafian follicles, successively developed in their solid substance. Nevertheless these ova do not fall into the peritoneal cavity, but are conveyed away by a special apparatus, consisting of the Fallopian tubes, which result from the modification of certain embryonic structures called the Mullerian ducts.The Mullerian ducts are canals which make their appearance alongside the ducts of the Wolffian bodies, but, throughout their whole extent, remain distinct from them. Their proximal ends lie close to the ovary, and become open and dilated to form the so-called ostia. Beyond these ostia they generally remain narrow for a space, but, toward their hinder openings into the genito - urinary part of the cloaca, they commonly dilate again. In all animals but the didelphous and monodelphous Mammalia, the Mullerian ducts undergo no further modification of any great morphological importance; but, in the monodelphous Mammalia, they become united, at a short distance in front of their posterior ends; and then the segments between the latter and the point of union, or still farther forward, coalesce into one. By this process of confluence the Mullerian ducts are primarily converted into a single vagina with two uteri opening into it; but, in most of the Monodelphia, the two uteri also more or less completely coalesce, until both Mullerian ducts are represented by a single vagina, a single uterus, and two Fallopian tubes. The didelphous Mammalia have two vaginae which may, or may not, coalesce anteriorly for a short extent; but the two uteri remain perfectly distinct. So that what takes place in them is probably, a differentiation of each Mullerian duct into Fallopian tube, uterus, and vagina, with or without the union of the two latter, to the extent to which it is effected in the earlier stages of development in Monodelphia. The Wolffian ducts of the female either persist as canals, the so-called canals of Gaertner, which open into the vagina, or disappear altogether. Remains of the Wolffian bodies constitute the parovaria, observable in certain female mammals.

In the male vertebrate embryo, the testis, or essential reproductive organ, occupies the same position, in front of the Wolffian body, as the ovary; and, like the latter, is composed of indifferent tissue. In Amphioxus and in the Marsipobranchii, this tissue appears to pass directly into spermatozoa; but, in most Vertebrata, it acquires a saccular or tubular structure, and from the epithelium of the sacs, or tubuli, the spermatozoa are developed. At first, the testis is as completely devoid of any excretory canal as the ovary; but, in the higher vertebrates, this want is speedily supplied by the Wolffian body, certain of the tubuli of which become continuous with the tubuli seminiferi, and constitute the vasa recta, while the rest abort.

The Wolffian duct thus becomes the vas deferens, or excretory duct of the testis; and its anterior end, coiling on itself, gives rise to the epididymis. A vesicula seminalis is a diverticulum of the vas deferens, near its posterior end, which serves as a receptacle for the semen.

If the Wolffian bodies, the genitalia, and the alimentary canal of a vertebrate embryo, communicated with the exterior by apertures having the same relative position as the organs themselves, the anus would be in front and lowest, the Wolffian apertures behind and highest, and the genital apertures would lie between the two. But the anal, genital, and urinary apertures are found thus related only among certain groups of fishes, such as the Teleostei. In all other Vertebrata there is either a cloaca, or common chamber, into which the rectum, genital, and urinary organs open; or, the anus is a distinct posterior and superior aperture, and the opening of a genito-urinary sinus, common to the urinary and reproductive organs, lies in front of it, separated by a more or less considerable perinaeum.

These conditions of adult Vertebrata repeat the states through which the embryo of the highest vertebrates pass. At a very early stage, an involution of the external integument gives rise to a cloaca, which receives the allantois, the ureters, the Wolffian and Mullerian ducts, in front, and the rectum behind. But, as development advances, the rectal division of the cloaca becomes shut off from the other, and opens by a separate aperture - the definitive anus, which thus appears to be distinct, morphologically, from the anus of an osse ous fish. For a time, the anterior, or genito-urinary part of the cloaca, is, to a certain extent, distinct from the rectal division, though the two have a common termination; and this condition is repeated in Aves, and in ornithodelphous Mammalia, where the bladder, the genital ducts, and the ureters, all open separately from the rectum into a genito-urinary sinus.

In the male sex, as development advances, this genitourinary sinus becomes elongated, muscular, and surrounded, where the bladder passes into it, by a peculiar gland, the prostate. It thus becomes converted into what are termed the fundus, and neck of the bladder, with the prostatic and membranous portions of the urethra. Concomitantly with these changes, a process of the ventral wall of the cloaca makes its appearance, and is the rudiment of the intromittent organ, or penis. Peculiar erectile vascular tissue, developed within this body, gives rise to the median corpus spongiosum and the lateral corpora cavernosa. The penis gradually protrudes from the cloaca; and, while the corpus spongiosum terminates the anterior end of it, as the glands, the corpora cavernosa attach themselves, posteriorly, to the ischia. The under, or posterior, surface of the penis is, at first, simply grooved; by degrees the two sides of the groove unite, and form a complete tube embraced by the corpus spongiosum. The penial urethra is the result.

Into the posterior part of this penial urethra, which is frequently dilated into the so-called bulbus urerthrae, glands, called Cowper's glands, commonly pour their secretion; and the penial, membranous, and prostatic portions of the urethra (genito-urinary sinus) uniting into one tube, the male definitive urethra is finally formed.

In sundry birds and reptiles, the penis remains in the condition of a process of the ventral wall of the cloaca, grooved on one face. In ornithodelpbous mammals the penial urethra is complete, but open behind, and distinct from the genito-urinary sinus. In the Didelphia the penial urethra and genito-urinary sinus are united into one tube, but the corpora cavernosa are not directly attached to the ischium.

Certain Reptilia possess a pair of eversible copulatory organs situated in integumentary sacs, one on each side of the cloaca, but it does not appear in what manner these penes are morphologically related to those of the higher Vertebrata.

In the female sex, the homologue of a penis frequently makes its appearance as a clitoris, but rarely passes beyond the stage of a grooved process with corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum - the former attached to the ischium, and the latter developing a glans. But, in some few mammals (e. g. the Lemuridae), the clitoris is traversed by a urethral canal.

In no vertebrated animal do the ovaries normally leave the abdominal cavity, though they commonly forsake their primitive position, and may descend into the pelvis. But, in many mammals, the testes pass out of the abdomen through the inguinal canal, between the inner and outer tendons of the external oblique muscle, and, covered by a fold of peritonaeum, descend temporarily or permanently into a pouch of the integument - the scrotum. In their course they become invested with looped muscular fibres, which constitute the cremaster. The cremaster retracts the testis into the abdominal cavity, or toward it, when, as in the higher mammals, the inguinal canal becomes very much narrowed or altogether obliterated. In most mammals the scrotal sacs lie at the sides of, or behind, the root of the penis, but in the Didelphia the scrotum is suspended by a narrow neck in front of the root of the penis.

In most mammals the penis is enclosed in a sheath of integument, the preputium; and, in many, the septum of the corpora cavernosa is ossified, and gives rise to an os penis.

In the female the so-called labia majora represent the scrotal, the labia minora the preputial, part of the male organ of copulation.

Organs not directly connected with reproduction, but in various modes accessory to it, are met with in many Vertebrata. Among these may be reckoned the integumentary pouches, in which the young are sheltered during their development in the male Pipefish (Syngnathus), in some female Amphibia (Notodelphys, Pipa), and Marsupialia; together with the mammary glands of the Mammalia.