Blood Group Antigens

Blood Group

Antigens ABO Blood Types

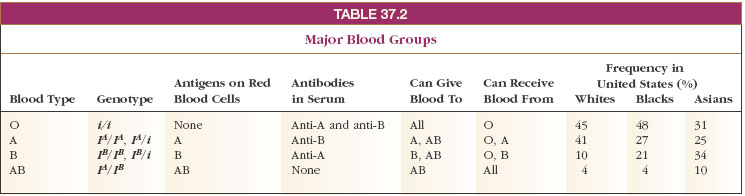

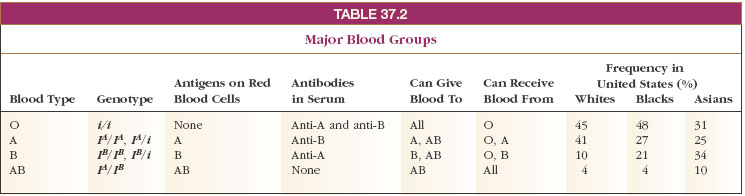

Blood cells differ chemically from person to person, and when two different (incompatible) blood types are mixed, agglutination (clumping together) of erythrocytes results. The basis of these chemical differences is naturally occurring antigens on the membranes of red blood cells. The best known of these inherited immune systems is the ABO blood group. Antigens A and B are inherited as codominant alleles of a single gene. Homozygotes for a recessive allele at the same gene have type O blood, which lacks A and B antigens. Thus, as shown in Table 37-2, an individual with, for example, genes IA/IA or IA/i develops A antigen (blood type A). The presence of an IB gene produces B antigens (blood type B), and for the genotype IA/IB both A and B antigens develop on the erythrocytes (blood type AB). Epitopes of A and B also are present on the surfaces of many epithelial and most endothelial cells.

There is an odd feature about the ABO system. Normally we would expect that a type A individual would develop antibodies against type B cells only if cells bearing B epitopes were first introduced into the body. In fact, type A persons acquire anti-B antibodies soon after birth, even without exposure to type B cells. Similarly, type B individuals come to carry anti-A antibodies at a very early age. Type AB blood has neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies (since if it did, it would destroy its own blood cells), and type O blood has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. There is evidence that the antibodies develop as a response to A and B epitopes on intestinal microorganisms when the intestine becomes colonized with bacteria after birth. Presumably, small and unnoticed infections with the bacteria occur. The antibodies thus produced cross-react with the A and B epitopes on erythrocytes.

We see then that the blood-group names identify their antigen content. Persons with type O blood are called universal donors because, lacking antigens, their blood can be infused into a person with any blood type. Even though it contains anti-A and anti-B antibodies, these are so diluted during transfusion that they do not react with A or B antigens in a recipient’s blood. Persons with AB blood are universal recipients because they lack antibodies to A and B antigens. In practice, however, clinicians insist on matching blood types to prevent any possibility of incompatibility.

Blood cells differ chemically from person to person, and when two different (incompatible) blood types are mixed, agglutination (clumping together) of erythrocytes results. The basis of these chemical differences is naturally occurring antigens on the membranes of red blood cells. The best known of these inherited immune systems is the ABO blood group. Antigens A and B are inherited as codominant alleles of a single gene. Homozygotes for a recessive allele at the same gene have type O blood, which lacks A and B antigens. Thus, as shown in Table 37-2, an individual with, for example, genes IA/IA or IA/i develops A antigen (blood type A). The presence of an IB gene produces B antigens (blood type B), and for the genotype IA/IB both A and B antigens develop on the erythrocytes (blood type AB). Epitopes of A and B also are present on the surfaces of many epithelial and most endothelial cells.

There is an odd feature about the ABO system. Normally we would expect that a type A individual would develop antibodies against type B cells only if cells bearing B epitopes were first introduced into the body. In fact, type A persons acquire anti-B antibodies soon after birth, even without exposure to type B cells. Similarly, type B individuals come to carry anti-A antibodies at a very early age. Type AB blood has neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies (since if it did, it would destroy its own blood cells), and type O blood has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. There is evidence that the antibodies develop as a response to A and B epitopes on intestinal microorganisms when the intestine becomes colonized with bacteria after birth. Presumably, small and unnoticed infections with the bacteria occur. The antibodies thus produced cross-react with the A and B epitopes on erythrocytes.

We see then that the blood-group names identify their antigen content. Persons with type O blood are called universal donors because, lacking antigens, their blood can be infused into a person with any blood type. Even though it contains anti-A and anti-B antibodies, these are so diluted during transfusion that they do not react with A or B antigens in a recipient’s blood. Persons with AB blood are universal recipients because they lack antibodies to A and B antigens. In practice, however, clinicians insist on matching blood types to prevent any possibility of incompatibility.