Inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation is a vital process in mobilization of body defenses against an invading organism or other tissue damage and in repair of damage thereafter. The course of events in the inflammatory process is greatly influenced by the prior immunizing experience of the body with the invader and by the duration of the invader’s presence or its persistence in the body. The processes by which an invader is actually destroyed, however, are themselves nonspecific. Manifestations of inflammation are delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) and immediate hypersensitivity, depending on whether the response is cell mediated or antibody mediated.

The DTH reaction is a type of CMI in which the ultimate effectors are activated macrophages. The term delayed type hypersensitivity is derived from the fact that a period of 24 hours or more elapses from the time of antigen introduction until a reponse is observed in an immunized subject. This is because TH1 cells with specific receptors in their surface for that particular antigen require some time to arrive at the antigen site, recognize the epitopes displayed by the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and become activated and secrete IL-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). TNF causes endothelial cells of the blood vessels to express on their surface certain molecules to which leukocytes adhere: first neutrophils and then lymphocytes and monocytes. TNF also causes endothelium to secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, which increase the mobility of leukocytes and facilitate their passage through the endothelium. TNF and IFN-γ also cause endothelial cells to change shape, favoring leakage of macromolecules and passage of cells. Escape of fibrinogen from blood vessels leads to conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, and the area becomes swollen and firm.

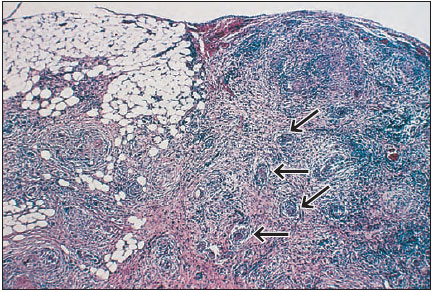

As monocytes pass out of blood vessels, they become activated macrophages, which are the main effector cells of a DTH. They phagocytize particulate antigen, secrete mediators that promote local inflammation, and secrete cytokines and growth factors that promote healing. If the antigen is not destroyed and removed, its chronic presence leads to deposition of fibrous connective tissue, or fibrosis. Nodules of inflammatory tissue called granulomas may accumulate around persistent antigen and are found in numerous parasitic infections (Figure 37-7).

Immediate hypersensitivity is quite important in some parasitic infections. This reaction involves degranulation of mast cells

in the area. Their surfaces

bear receptors for Fc portions of antibody,

especially IgE. Occupation of

these sites by antigen-specific antibodies

enhances degranulation of mast

cells when the Fab portions bind the

particular antigen. There is a rapid

release of several mediators, such as

histamine, that cause dilation of local

blood vessels and increased vascular

permeability. Escape of blood plasma

into the surrounding tissue causes

swelling (wheal), and engorgement of

vessels with blood produces redness,

the characteristic flare (Figure 37-8).

Systemic immediate hypersensitivity is

anaphylaxis, which may be fatal if

not treated rapidly. The swelling and

change in permeability of capillaries

allow antibodies and leukocytes to

move from capillaries and easily reach

the invader. The first phagocytic line of

defense is neutrophils, which may last

a few days, then macrophages (either

fixed or differentiated from monocytes)

become predominant.

Some degree of cell death (necrosis) always occurs in inflammation, but necrosis may not be prominent if the inflammation is minor. When the necrotic debris is confined within a localized area, the pus (spent leukocytes and tissue fluid) may increase in hydrostatic pressure, forming an abscess. An area of inflammation that opens out to a skin or mucous surface is an ulcer.

Immediate hypersensitivity in humans is the basis for allergies and asthma, which are quite undesirable conditions, leading one to wonder why they evolved. Some scientists believe that the allergic response originally evolved to help the body ward off parasites because only allergens and parasite antigens stimulate production of large quantities of IgE. Avoidance of or reduction in effects of parasites would have conferred a selective advantage in human evolution. The hypothesis is that in absence of heavy parasitic challenge, the immune system is free to react against other substances, such as ragweed pollen. People now living where parasites remain abundant are less troubled with allergies than are those living in relatively parasite-free areas.

Inflammation is a vital process in mobilization of body defenses against an invading organism or other tissue damage and in repair of damage thereafter. The course of events in the inflammatory process is greatly influenced by the prior immunizing experience of the body with the invader and by the duration of the invader’s presence or its persistence in the body. The processes by which an invader is actually destroyed, however, are themselves nonspecific. Manifestations of inflammation are delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) and immediate hypersensitivity, depending on whether the response is cell mediated or antibody mediated.

The DTH reaction is a type of CMI in which the ultimate effectors are activated macrophages. The term delayed type hypersensitivity is derived from the fact that a period of 24 hours or more elapses from the time of antigen introduction until a reponse is observed in an immunized subject. This is because TH1 cells with specific receptors in their surface for that particular antigen require some time to arrive at the antigen site, recognize the epitopes displayed by the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and become activated and secrete IL-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). TNF causes endothelial cells of the blood vessels to express on their surface certain molecules to which leukocytes adhere: first neutrophils and then lymphocytes and monocytes. TNF also causes endothelium to secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, which increase the mobility of leukocytes and facilitate their passage through the endothelium. TNF and IFN-γ also cause endothelial cells to change shape, favoring leakage of macromolecules and passage of cells. Escape of fibrinogen from blood vessels leads to conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, and the area becomes swollen and firm.

|

| Figure 37-7 Granulomatous reaction around eggs (arrows) of Schistosoma mansoni in mesenteries. |

As monocytes pass out of blood vessels, they become activated macrophages, which are the main effector cells of a DTH. They phagocytize particulate antigen, secrete mediators that promote local inflammation, and secrete cytokines and growth factors that promote healing. If the antigen is not destroyed and removed, its chronic presence leads to deposition of fibrous connective tissue, or fibrosis. Nodules of inflammatory tissue called granulomas may accumulate around persistent antigen and are found in numerous parasitic infections (Figure 37-7).

Immediate hypersensitivity is quite important in some parasitic infections. This reaction involves degranulation of mast cells

|

| Figure 37.8 Wheal and flare reactions around sites of antigen injection for allergy testing. |

Some degree of cell death (necrosis) always occurs in inflammation, but necrosis may not be prominent if the inflammation is minor. When the necrotic debris is confined within a localized area, the pus (spent leukocytes and tissue fluid) may increase in hydrostatic pressure, forming an abscess. An area of inflammation that opens out to a skin or mucous surface is an ulcer.

Immediate hypersensitivity in humans is the basis for allergies and asthma, which are quite undesirable conditions, leading one to wonder why they evolved. Some scientists believe that the allergic response originally evolved to help the body ward off parasites because only allergens and parasite antigens stimulate production of large quantities of IgE. Avoidance of or reduction in effects of parasites would have conferred a selective advantage in human evolution. The hypothesis is that in absence of heavy parasitic challenge, the immune system is free to react against other substances, such as ragweed pollen. People now living where parasites remain abundant are less troubled with allergies than are those living in relatively parasite-free areas.