Environment and the Niche

Environment and

the Niche

An animal’s environment is composed of all conditions that directly affect its chances of survival and reproduction. These factors include space, forms of energy such as sunlight, heat, wind and water currents, and also materials such as soil, air, water, and chemicals. The environment also includes other organisms, which can be an animal’s food, or its predators, competitors, hosts, or parasites. The environment thus includes both abiotic (nonliving) and biotic (living) factors. Some environmental factors, such as space and food, are utilized directly by an animal, and these are called resources.

A resource may be expendable or nonexpendable, depending on how an animal uses it. Food is expendable, because once eaten it is no longer available. Food therefore must be continuously replenished in the environment. Space, whether total living area or a subset such as the number of suitable nesting sites, is not exhausted by being used, and thus is nonexpendable.

The physical space where an animal lives, and that contains its environment, is its habitat. Size of the habitat is variable and depends upon the spatial scale under consideration. A rotten log is a normal habitat for carpenter ants. Such logs occur in larger habitats called forests where deer also are found. However, deer forage in open meadows, so their habitat is larger than the forest. On a larger scale, some migratory birds occupy forests of the north temperate region during summer and move to the tropics during winter. Thus, habitat is defined by the normal activity exhibited by an animal, rather than by arbitrary physical boundaries.

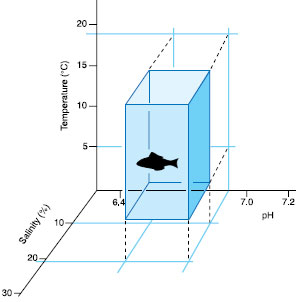

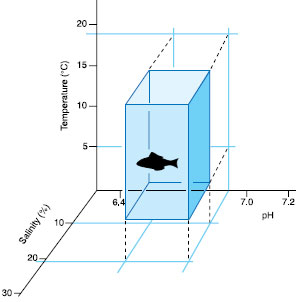

Animals of any species have certain

environmental limits of temperature,

moisture, and food within which

they can grow, reproduce, and survive.

A suitable environment therefore

must simultaneously meet all

requirements for life. A freshwater

clam living in a tropical lake could

tolerate the temperature of a tropical

ocean, but would be killed by the

ocean’s salinity. A brittle star living in

the Arctic Ocean could tolerate the

salinity of the tropical ocean but not

its temperature. Thus temperature

and salinity are two separate dimensions

of an animal’s environmental

limits. If we add another variable,

such as pH, we increase our description

to three dimensions (Figure 40-1).

If we consider all environmental conditions

that permit members of a

species to survive and multiply, we

define the role of that species in

nature as distinguished from all others.

This unique, multidimensional

fingerprint of a species is called

its niche.

Dimensions of the niche vary among

members of a species, making the

niche subject to evolution by natural

selection. The niche of a species undergoes evolutionary changes over

successive generations.

Animals may be generalists or specialists with respect to tolerance of environmental conditions. For example, most fish are adapted to live in either fresh water or seawater, but not both. However, those that live in salt marshes, such as the minnow Fundulus heteroclitus, easily tolerate changes in salinity that occur over tidal cycles in these estuarine habitats as fresh water from the land mixes with seawater. Similarly, whereas most snakes are capable of eating a wide variety of animal prey, others have narrow dietary requirements; for example, the African snake Dasypeltis scaber is specialized to eat bird eggs (Figure 34-3).

However broad may be the tolerance limits of an animal, it experiences only a single set of conditions at a time. In fact, an animal probably will not experience in the course of its lifetime all environmental conditions that it potentially can tolerate. Thus, we must distinguish an animal’s fundamental niche, which describes its potential role, and its realized niche, the subset of potentially suitable environments that an animal actually experiences.

An animal’s environment is composed of all conditions that directly affect its chances of survival and reproduction. These factors include space, forms of energy such as sunlight, heat, wind and water currents, and also materials such as soil, air, water, and chemicals. The environment also includes other organisms, which can be an animal’s food, or its predators, competitors, hosts, or parasites. The environment thus includes both abiotic (nonliving) and biotic (living) factors. Some environmental factors, such as space and food, are utilized directly by an animal, and these are called resources.

A resource may be expendable or nonexpendable, depending on how an animal uses it. Food is expendable, because once eaten it is no longer available. Food therefore must be continuously replenished in the environment. Space, whether total living area or a subset such as the number of suitable nesting sites, is not exhausted by being used, and thus is nonexpendable.

The physical space where an animal lives, and that contains its environment, is its habitat. Size of the habitat is variable and depends upon the spatial scale under consideration. A rotten log is a normal habitat for carpenter ants. Such logs occur in larger habitats called forests where deer also are found. However, deer forage in open meadows, so their habitat is larger than the forest. On a larger scale, some migratory birds occupy forests of the north temperate region during summer and move to the tropics during winter. Thus, habitat is defined by the normal activity exhibited by an animal, rather than by arbitrary physical boundaries.

| Figure 40-1 Three-dimensional niche volume of a hypothetical animal showing three tolerance ranges. This raphic representation is one way to show the ultidimensional nature of environmental relations. This representation is incomplete, however, b ecause additional environmental factors also influence growth, reproduction, and survival |

Animals may be generalists or specialists with respect to tolerance of environmental conditions. For example, most fish are adapted to live in either fresh water or seawater, but not both. However, those that live in salt marshes, such as the minnow Fundulus heteroclitus, easily tolerate changes in salinity that occur over tidal cycles in these estuarine habitats as fresh water from the land mixes with seawater. Similarly, whereas most snakes are capable of eating a wide variety of animal prey, others have narrow dietary requirements; for example, the African snake Dasypeltis scaber is specialized to eat bird eggs (Figure 34-3).

However broad may be the tolerance limits of an animal, it experiences only a single set of conditions at a time. In fact, an animal probably will not experience in the course of its lifetime all environmental conditions that it potentially can tolerate. Thus, we must distinguish an animal’s fundamental niche, which describes its potential role, and its realized niche, the subset of potentially suitable environments that an animal actually experiences.