Nutrient Cycles

Nutrient Cycles

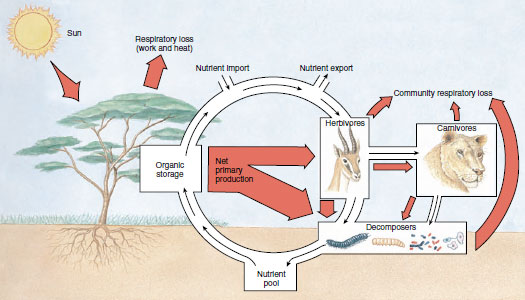

All elements essential for life are derived from the environment, where they are present in air, soil, rocks, and water. When plants and animals die and their bodies decay, or when organic substances are burned or oxidized, elements and inorganic compounds essential for life processes (nutrients) are released and returned to the environment. Decomposers fulfill an essential role in this process by feeding on the remains of plants and animals and on fecal material. The result is that nutrients flow in a perpetual cycle between biotic and abiotic components of the ecosystem. Nutrient cycles are often called biogeochemical cycles because they involve exchanges between living organisms (bio-) and rocks, air, and water of the earths’ crust (geo-). Continuous input of energy from the sun keeps nutrients flowing and the ecosystem functioning (Figure 40-15).

We tend to think of biogeochemical cycles in terms of naturally occurring elements, such as water, carbon, and nitrogen. In recent times, however, humans have added synthetic materials to the biosphere that have entered food webs, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Probably the most harmful of these materials, in terms of ecosystemic processes, are pesticides. We currently produce about 2.5 million tons of pesticides worldwide, mainly for protection of crops from insects.

Despite such extensive use of poison, more than half of our crops are lost either before or after harvest to pests. The role of pesticides in natural food webs can be insidious for three reasons. First, many pesticides become concentrated as they travel up succeeding trophic levels. The highest concentrations will occur in the biomass of top carnivores such as hawks and owls, diminishing their ability to reproduce. Second, many species that are killed by pesticides are not pests, but merely innocent bystanders, called nontarget species. Nontarget effects happen when pesticides move out of the agricultural field to which they were applied,through rainwater runoff, leaching through the soil, or dispersal by wind. The third problem is persistence; some chemicals used as pesticides have a long life span in the environment, so that nontarget effects persist long after the pesticides have been applied. Scientists are working to create new pesticides that are more specific in their effects and decompose faster in the environment, but we have a long way to go to limit our warfare against those animals that compete with us for our supply of food.

All elements essential for life are derived from the environment, where they are present in air, soil, rocks, and water. When plants and animals die and their bodies decay, or when organic substances are burned or oxidized, elements and inorganic compounds essential for life processes (nutrients) are released and returned to the environment. Decomposers fulfill an essential role in this process by feeding on the remains of plants and animals and on fecal material. The result is that nutrients flow in a perpetual cycle between biotic and abiotic components of the ecosystem. Nutrient cycles are often called biogeochemical cycles because they involve exchanges between living organisms (bio-) and rocks, air, and water of the earths’ crust (geo-). Continuous input of energy from the sun keeps nutrients flowing and the ecosystem functioning (Figure 40-15).

|

| Figure 40-15 Nutrient cycles and energy flow in a terrestrial ecosystem. Note that nutrients are recycled, whereas energy flow (red) is one way. |

We tend to think of biogeochemical cycles in terms of naturally occurring elements, such as water, carbon, and nitrogen. In recent times, however, humans have added synthetic materials to the biosphere that have entered food webs, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Probably the most harmful of these materials, in terms of ecosystemic processes, are pesticides. We currently produce about 2.5 million tons of pesticides worldwide, mainly for protection of crops from insects.

Despite such extensive use of poison, more than half of our crops are lost either before or after harvest to pests. The role of pesticides in natural food webs can be insidious for three reasons. First, many pesticides become concentrated as they travel up succeeding trophic levels. The highest concentrations will occur in the biomass of top carnivores such as hawks and owls, diminishing their ability to reproduce. Second, many species that are killed by pesticides are not pests, but merely innocent bystanders, called nontarget species. Nontarget effects happen when pesticides move out of the agricultural field to which they were applied,through rainwater runoff, leaching through the soil, or dispersal by wind. The third problem is persistence; some chemicals used as pesticides have a long life span in the environment, so that nontarget effects persist long after the pesticides have been applied. Scientists are working to create new pesticides that are more specific in their effects and decompose faster in the environment, but we have a long way to go to limit our warfare against those animals that compete with us for our supply of food.