Infection in the hospital environment

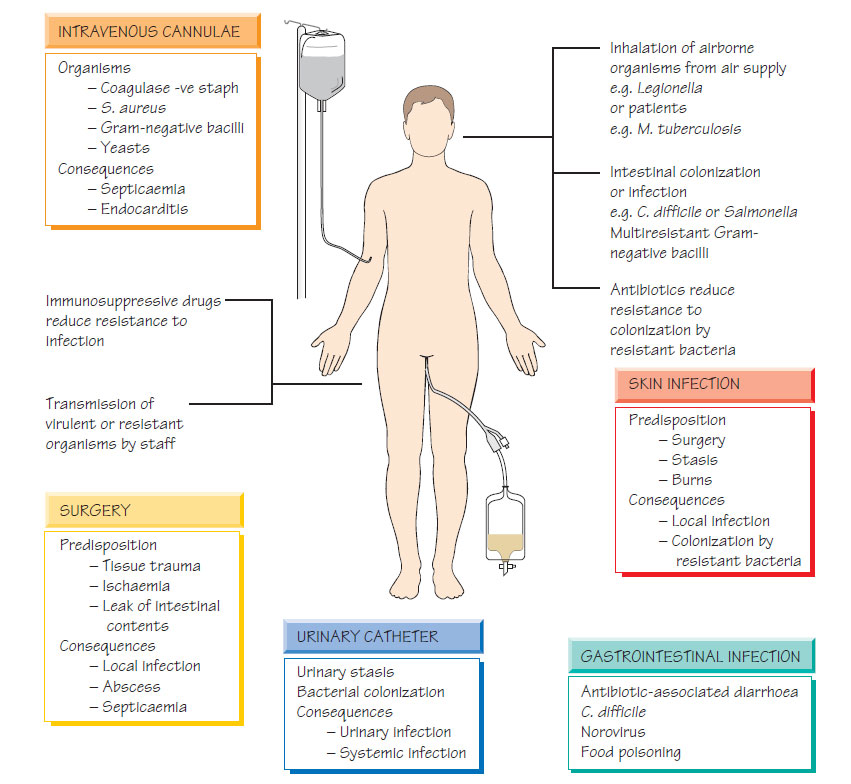

Infection is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in patients admitted to hospital. The most frequent types of infection are urinary tract, respiratory, wound, skin and soft-tissue infections, and septicaemia, which is often associated with vascular access.The environment

Food supply

Food is usually prepared centrally in the hospital kitchens. Patients are at risk of food-borne infection if hygiene standards fall; this route can transmit antibiotic-resistant organisms to immunocompromised patients who are especially vulnerable.

Pathogens (e.g. multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, respiratory viruses or bacteria) may be transmitted via theatre air supply and air-conditioning systems. Badly maintained air-conditioning systems may be a source of Legionella.

Fomites

Any inanimate object may be contaminated with organisms and act as a vehicle (fomite) for transmission. This is important for doctors performing procedures on patients with instruments that might be contaminated and transmit infection (e.g. MRSA on stethoscopes).

Water supply

The water supply in a hospital is a complex system, supplying water to wash-hand basins and showers, central heating and airconditioning systems. Legionella spp. may colonize the system in redundant areas of pipework and cooling-tower systems are a particular risk. When systems fail, organisms such as Legionella can be transmitted by the air-conditioning system. To reduce this risk, hot-water supplies should be maintained at a temperature above 45°C and cold-water supplies below 20°C.

Hospital patients are susceptible to infection as a result of underlying illness or treatment, for example patients with leukaemia or those receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. Age and immobility may predispose to infection; ischaemia may make tissues more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

Medical activities

Intravenous access

This is the most frequent source of healthcare-associated bacteraemia. The risk of infection from any intravenous device increases with the length of time it remains in position. Having broken the skin's integrity, it provides a route for invasion by skin organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium jeikeium. Signs of inflammation at the puncture site may be the first evidence of infection. Cannula-related infection can be complicated by septicaemia, endocarditis and metastatic infections (e.g. osteomyelitis). The risk of sepsis can be reduced by aseptic technique at insertion, as well as the choice of device, for instance those without side ports and dead spaces. Maintaining an adequate dressing and ensuring good staff hygiene when they are working with the device are equally important. The cannula site should be regularly inspected and this is particularly important in unconscious patients. Peripheral lines should be resited every 48 h; central and tunnelled lines should be changed when there is evidence of infection.

Indwelling urinary catheters bypass the normal defences and provide a route for ascending infection into the bladder. Risks can be minimized by aseptic technique when the catheter is inserted and handled.

Respiratory

Intubation bypasses the defences of the respiratory tract. Postoperative pain, immobility and the effects of anaesthesia predispose to pneumonia by reducing coughing. Respiratory infections with resistant Gram-negative organisms that originate from the hospital environment may occur. Inhalation of oral contents is reduced by raising the head of the bed in seriously ill patients.

Surgery

Surgical patients often have other health problems that are unrelated to their surgical complaint (e.g. asthma or diabetes mellitus), which may predispose them to infection. Surgery is traumatic and carries a risk of infection (e.g. especially wound infections).

To minimize the risk of infection during an operation, theatres are supplied with a filtered air supply. Staff movement during procedures should be limited to reduce air disturbance. Changing clothing reduces transmission of organisms from the wards. Impervious materials reduce contamination from the skin of the surgical team but are uncomfortable to wear. Some hospitals provide ventilated air-conditioned suits for surgical teams performing prosthetic joint surgery.

Antibiotic prophylaxis reduces postoperative infection rates. Antibiotics should be bactericidal, have sufficient penetration for the required site and be chosen on the basis of the operation type - see below. There is no evidence that continuing prophylaxis beyond 48 h is beneficial.

'Clean' involving the skin or a normally sterile site (e.g. a joint). Antibiotics are unnecessary unless a prosthetic device is inserted.

'Contaminated' where a viscus with a normal flora is breached. Antibiotics such as metronidazole and a second-generation cephalosporin for large-bowel surgery; a cephalosporin alone is satisfactory in surgery of the upper gastrointestinal or biliary tracts where anaerobes are rarely implicated.