Pathogenicity and pathogenesis of infectious disease

Definitions Humans encounter bacteria, viruses and parasites that do not cause disease. An infection occurs when microorganisms cause ill-health.| Term | Definition | |

| Pathogen | An organism capable of causing disease | |

| Commensal | An organism that is part of the normal flora | |

| Pathogenicity | The ability to cause disease | |

| Virulence | The ability to cause severe disease |

The capsule of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a pathogenicity determinant because without it the organism does not usually cause disease. Some capsular types cause more serious disease i.e. they are more virulent (Streptococcus pneumoniae, other Gram-positive cocci and the alpha-haemolytic streptococci). The term parasite is often used to describe protozoan and metazoan organisms, but this is confusing as these organisms may be either pathogens or commensals.

Obligate pathogens are always associated with disease (e.g. Treponema pallidum and HIV). Conditional pathogens may cause disease if certain conditions are met. For example, Bacteroides fragilis is a normal commensal of the gut but if it invades the peritoneal cavity, it will cause severe infection. Opportunistic pathogens usually cause infection when the host defences are compromised. For example, Pneumocystis jiroveci usually causes lung infection only in a host who has severely compromised T-cell immunity.

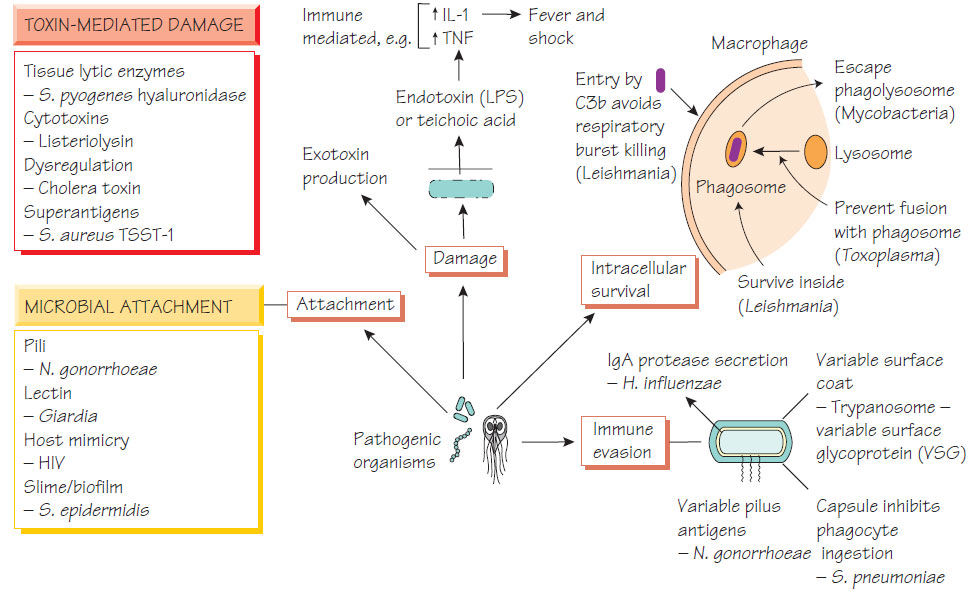

Mechanisms of pathogenicity

The process of infection has several stages.

Access to a vulnerable host - transmission

Organisms are transmitted by various means but most are restricted to a particular route (Sources and transmission of infection). Strains may develop epidemic potential by developing adaptation to an environment that either favours transmission or better survival in that environment. For example, most respiratory pathogens induce coughing, which facilitates their spread by the creation of respiratory droplets. The vomiting and diarrhoea associated with organisms that are spread by the faecal-oral route increase contamination of the environment and the risk of new infection.

Microorganisms must attach themselves to host tissues to colonize them and each organism has a different strategy. The distribution of the receptors to which a particular organism can bind will define the organs that it will infect, as in the following examples.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae adheres to the genital mucosa using fimbriae.

- Influenza virus attaches by its haemagglutinin antigen. This accounts for both species-specific pathogenesis (the ability of certain strains to cause disease in a particular species, such as avian or porcine strains) and intraspecies variation in affinity and susceptibility (Influenza viruses).

- Bacterial biofilms aid colonization of indwelling prosthetic devices, such as catheters and the respiratory tract. Some strains of staphylococci have genes that mediate attachment to plastics and to the biological molecules that coat intravascular devices.

- Mucosal destruction may expose a variety of host molecules such as fibronectin, vibronectin and collagen to which invading organisms can bind.

Some bacteria have mechanisms that help them get close to the mammalian epithelium. For example, Vibrio cholerae excretes a mucinase to help it reach the enterocyte. Microorganisms have a variety of strategies that allow them to cross mucosal barriers or different types of cell membrane.

Motility

The ability to move in order to locate new sources of food or in response to chemotactic signals potentially enhances pathogenicity. V. cholerae is motile by virtue of its flagellum - non-motile mutants are less virulent.

To survive in the human host, pathogens must overcome the host immune defences.

- Respiratory bacteria secrete an IgA protease that degrades host immunoglobulin.

- Staphylococcus aureus expresses protein A, which binds host immunoglobulin, preventing opsonization and complement activation.

- S. pneumoniae has a polysaccharide capsule, which inhibits phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

- Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania donovani and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are adapted to survive within macrophages using different mechanisms.

- The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative organisms makes them resistant to the effect of complement.

- Trypanosoma alter surface antigens to evade antibodies.

Damaging the host

Toxins

Endotoxins

Endotoxins stimulate macrophages to produce cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) that cause fever and shock.

Bacterial exotoxins can cause local or distant damage. They are usually proteins and may have a subunit structure.

- Cholera toxin B subunit binds to the epithelial cell and the A subunit activates adenyl cyclase, which results in sodium and chloride efflux from the cell, thus causing diarrhoea.

- Staphylococcal enterotoxins act as superantigens, causing nonspecific activation of T cells that have compatible variable region structure, which results in intense cytokine production leading to fever, shock, gastrointestinal disturbance and rash.

- Diphtheria toxin and Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A stop protein production by blocking elongation of proteins.

- Clostridial toxins interfere with neurological or neuromuscular signalling causing, for example, tetanus and botulism.